Introduction

In August 2022, I traveled to the University of Chicago to study documents in the university's Official Publications of India collection housed in the Regenstein Library. I undertook this trip as I was about to begin my fifth year of my Ph.D. program at the University of California, Davis, and was working as a researcher and writer for the One More Voice. Despite my involvement with this project, which engages heavily with archival materials, my trip to the Regenstein was my first visit to a physical archive to conduct research. This experience introduced me to many topics detailed in the archived documents themselves; it also taught me about the logistics, skills, and attentions necessary to conduct this sort of research. This essay offers my reflections on conducting archival research for the first time in hopes of offering pragmatic tips and grounding anecdotes for other early-career researchers who may find themselves in a similar situation, while also providing some insight into the work I undertook for the “BIPOC Voices” project.

In addition to heeding my advice, I encourage researchers at any stage of their career to benefit from the wisdom in the “BIPOC Voices” set of recommendations (PDF) for working in colonial archives, which equipped me with invaluable guidance for my archival trip. The seven core recommendations in those recommendations will be useful to those entering the archive for the first time even if their research may not be explicitly about racialized voices and/or colonial archives. The recommendations prompted me to specify my research focus, proactively contact a librarian who oversees the collection, and prepared me to be attentive and flexible when I was working with the documents in the archive.

Selecting the Archive

The Official Publications of India is an extensive collection of government, military, and administrative documents. Martin Moir (1998, ix), in his guide to the collection, remarks that the archives “mainly derive from and reflect the activities and responsibilities of the India Office (1858-1947), the Burma Office (1937-48), the East India Company (1600-1858) and the Board of Control (1784-1858).” The British Library houses the bulk of these records, but the library deposited over 20,000 duplicate volumes at the Regenstein Library, the main library for the University of Chicago, on permanent loan.

The documents are uniquely searchable thanks to a database maintained by the Regenstein Library. The database allows researchers to search by author, date, publisher, city, subject, or notes. The tool is useful but quirky, and, like many electronic research tools, requires some finesse, creativity, and flexibility; it took me an hour or two to get used to using it. The Regenstein’s collection is also distinctive because it allows researchers to browse it themselves, as opposed to non-browsable collections that require researchers to request select materials ahead of time for archivists or librarians to procure.

The choice to visit this collection stemmed from its relevance as well as its convenience. To aid me in an essay for One More Voice that I was writing on missionary education efforts, I wanted to find official documents to help me better understand the British government’s attempts to “modernize” the Indian education system in the second half of the nineteenth century. In particular, I sought to explore how missionary schooling dovetailed with government efforts to institutionalize education in the British colony.

This topical focus was broad, but before I could further narrow my focus, I had to account for the logistical constraints of a germane archival visit. My budget necessitated regional travel and necessitated a relatively brief trip, so I needed to visit an institution proximate to either northern California (where I spent the first half of my summer in 2022) or Minneapolis, Minnesota (where I spent the second half). I settled on the Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago because their Southern Asia Collections were by far the most extensive that I could find in the geographies available to me.

Within the University’s collection, I found that The Official Publications of India holdings suited both my research focus and logistical needs. I used the database to confirm that the Regenstein’s holdings included materials on education, and my initial search confirmed the presence of annual reports on topics ranging from different regions’ primary schooling systems to the development of professional schooling and schooling for women. The database also provided contact information for the librarian, Laura Ring, who oversees the collection and its access.

After confirming the collection’s relevance for my project, I reached out to Ring about how to access the materials. I met with Ring over Zoom to discuss the collection and learn about the logistics of the visit itself. She provided invaluable tips for further navigating the online database so I could find the call numbers of material that I would want to locate when visiting the collection.

Ring also directed me to two guides written about the collection – including the one I cite above (Moir 1998) – which helped me learn about the collection’s history and scope. Most importantly, Ring walked me through the steps I would take to access the collection from securing a visiting researcher pass to where I would set up my workstation in the library to how to navigate the daunting stacks of volumes. She also informed me that all the material was out of copyright, but that physical materials could not leave the room where they were stored.

This information shaped the way I planned to structure my time at the Regenstein. I decided that I would take photos of as many relevant materials as I could during my visit and wait until after my trip to read and take notes on the materials since I could take and use the digital copies however I pleased, whereas my access to the physical records was temporally limited.

Getting and Staying There

To fund the trip, I drafted a proposed budget and brief rationale for the trip and submitted it to Adrian S. Wisnicki, lead developer of One More Voice and one of the two co-PIs on the “BIPOC Voices” project. Dr. Wisnicki was able to secure the necessary funding by combining the remainder of “BIPOC Voices” funding with an equal in-kind contribution provided by Dino Franco Felluga, general editor of COVE and the other co-PI on the project. Once my funding was approved, I booked a flight in accordance with my transportation budget. Dr. Wisnicki, who had previously attended the University of Chicago, was also instrumental in helping me select an ideal lodging location that was both close to the library and safe since I was unfamiliar with the neighborhoods surrounding the university.

Packing was the final frontier of preparations once I had sorted out my travel and research logistics. My Mac computer and iPhone were my primary research tools, as well as a phone tripod that facilitated fast and uniform photography of the materials. By using my Mac and iPhone in combination, I was able to transfer images quickly from the latter to the former while also ensuring their integrity. Other useful supplies included my water bottle, earbuds, and power pack (to charge my phone without an outlet). It was summer in Chicago, and my main mode of transportation between the library and my lodging was walking in the sunshine. However, the library was thoroughly air-conditioned, so I was glad that I had erred on the side of over-packing, which gave me lots of layers to choose from.

In the Archive

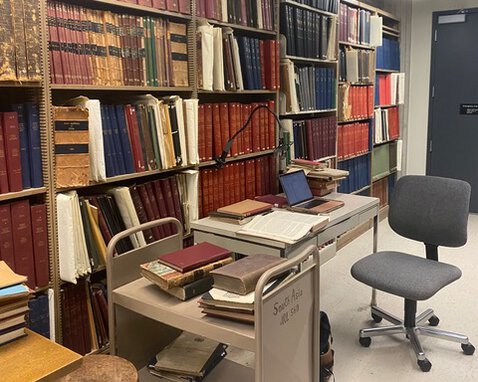

I arrived at the Regenstein each morning of my visit at or shortly after 9 am because my access to the collection was incumbent on library employees being present to let me into the area where the materials were stored. On my first day, I was shown the proper entrance to the collection by a librarian, Greg Flemming, who was assisting Ring in her absence. The collection was relatively consolidated and organized; my workstation was among the stacks and pleasantly tucked away from distractions or other library users (see header image for this essay). Yet, the amount of records I faced was tremendous. The scale of administration and human output necessary to create, not to mention maintain, so many records was likewise staggering to me; the massive volumes I photographed were just a minute fraction of the information available in that room, offering only slivers of understanding about the colonial apparatus of Britain in India during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In accordance with my plans, the majority of my workday consisted of photographing materials for later reference. In my browsing, I also unexpectedly found a cache of reports simply entitled “Education in India,” which reported comprehensive information about the state of the education system in colonial India, so I ended up with more material than I could possibly document. To narrow my scope, I decided to focus on reports from a narrow range of dates and, when possible, from a particular geographic region. These filters helped me focus on documents that would have the greatest bearing on my article, but it was challenging to flip through or set aside volumes that, while not meeting these criteria, still struck me as interesting. I erred on the side of capturing full reports rather than sub-sections or just introductory material because I was not certain which sort of data or information would be useful to my project.

I photographed government records that detailed qualitative and quantitative data about the Indian education system. These records were either annual reports or retrospectives that spanned several years (but never more than a decade). These reports stratified schools by geography and age-level and, for each sub-category, presented salient metrics for determining the scope and effectiveness of education programs. Especially in reports pertaining to higher education, these documents also included substantial narrative portions in which government officials described the successes and shortcomings of a specific institution or program within a university and advised further action to ensure greater reach and efficacy of the burgeoning education infrastructure.

The work moved faster as time went on, but the initial setup required some trial and error. Connecting to the internet, setting up the tripod correctly, securing the materials (and incorporating new discoveries), and automating the transfer of photos from my phone to computer all took time to streamline. Even as the processes got more efficient, other aspects of the labor remained or became increasingly challenging. It was uncomfortable to hunch over the tripod, my eyes got worn out from staring at screens in a windowless room, and I kept sneezing and sniffling from the prodigious amount of dust in the room.

I spent between five and six hours each day sifting through and photographing records as well as two or three hours doing supporting work such as reading guides of the collection (which were only available for use inside the library), backing up photographs, updating my list of call numbers to seek out, and doing contextual research. The time went by quickly, and I felt thoroughly spent by the end of my fourth day.

Afterwards

Sorting the photographs into folders for each item allowed me to easily access and move through the material I collected after the fact. Most of the pages I captured did not convey information that made its way into my article, but having complete items helped me better contextualize and subsequently understand the smaller excerpts that did prove useful to my research topic. In this sense, sifting through the shelves of volumes while in the library served as a rehearsal of sorts for sifting through the digital records I created after the fact. Although I had tried to narrow my focus while in the archive, after the fact I still felt like my pursuit could have benefited from even more narrow parameters or perhaps a more pointed research question. Of course, perfect efficiency is a mythic horizon, but when there is so much information available in an archive, even a relatively focused scope still results in a surprisingly bulky output.

Conclusion

Preparing for and executing an archival research visit is a solitary pursuit, but the success of my trip was predicated on collaboration and support from others, both formal and informal. I also left my visit with an appreciation of the myriad idiosyncrasies that make it challenging to generalize about all archival research. However, whenever I next return to an archive, I will carry with me the knowledge that no amount of preparation can prevent moments of improvisation or mistakes; flexibility is as important as preparation. I’ll be better prepared to ask questions that feel basic or simple at every step of the process. And, finally, I will have an appreciation of the fact that curiosity needs to be tempered by pragmatism, though not wholly overshadowed by it.

Acknowledgements

Above all, Dr. Wisnicki supported me by providing logistical and topical parameters, technical instructions, and insight about the area I would be visiting. His guidance and advocacy ensured I was materially, logically, and emotionally supported for my inaugural research trip. Librarians Laura Ring and Greg Fleming at the Regenstein equipped me with crucial knowledge and access to pursue answers to my research questions and be surprised by new resources. I also relied on the guidance generously provided by other graduate students and early-career researchers – most notably the unfailing Allison Fulton. Finally, my friends outside of academia who lived near the library brightened my days, fed me, and – in doing so – helped me bring my best self to my work in the stacks.

Works Cited

Moir, Martin. 1988. A General Guide to the India Office Records. London: The British Library.