Overview

Philip Cohen Labatt, who sometimes published as P.C.L., was a Jamaican Jewish writer and editor. His father, Robert Labatt, was a descendant of Sephardi Jews, a group whose expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula by the Spanish Inquisition brought them to the Caribbean; the name and ancestry of his mother are unknown. According to Synagogue records, Philip Cohen Labatt was born “illegitimate” in Jamaica in 1823 (Kaufman 2019, 69). The birth record does not mention his mother’s identity. This missing information combined with the existence of a large population of bi-racial Jews living in Kingston at this time make it difficult to determine with certainty if Labatt was bi-racial or white (69-70). Little is otherwise known of Labatt’s short life, which ended in 1854 just before his thirty-third birthday.

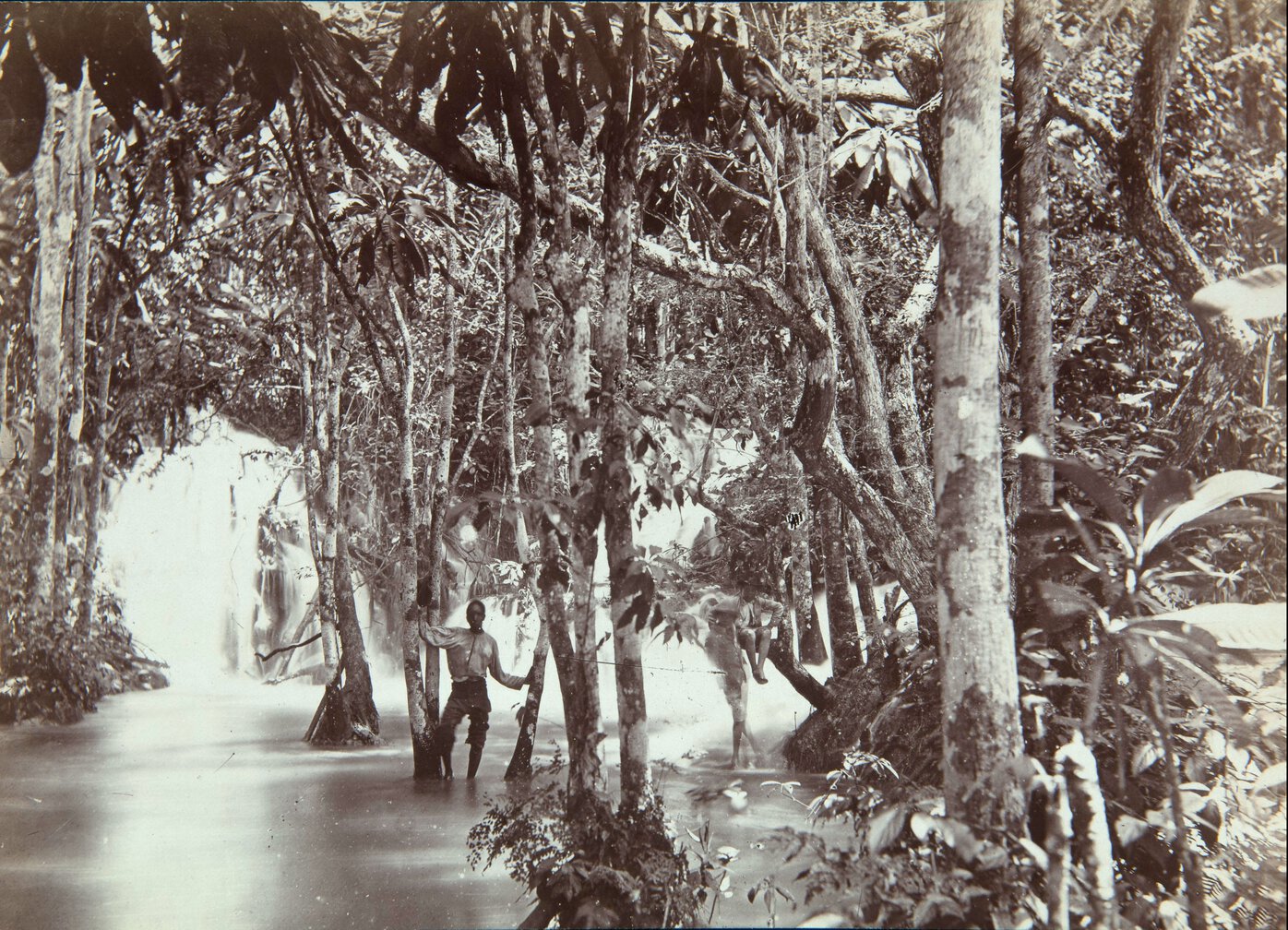

Labatt’s writing, much of which is anti-colonial, draws from both British and Afro-Jamaican literary and oral cultures. This essay provides background on Labatt's writing, including his position as editor of the Jamaican Daily Gleaner, and concludes with a discussion about two of Labatt’s short stories published on One More Voice. In the first, “Curgy’s Funeral, Or the Old Time Busha” (1855, 30-35), Labatt uses farce to depict Obeah and tricksterism on a Jamaican plantation. Labatt sets a second short story, “An Incident in the Late Rebellion in Jamaica” (1855, 36-47), during the Sam Sharpe Rebellion (also sometimes called the Baptist War or Christmas Rebellion) and alludes to Queen Nanny, an historical figure from the previous century mythologized in literary and oral culture in the nineteenth century and beyond. Both stories offer prominent and historically-situated accounts of pre-emancipation resistance to slavery.

As a Jamaican-born Jew and possibly a bi-racial writer, Labatt’s work signals many of the complexities of racial constructions in the nineteenth-century Caribbean. According to Jane Gerber (2014, 11), Jamaican Jews acquired full civil rights in 1831, “six months after the free blacks and three years before the general abolition of slavery.” Kay Dian Kriz (2017, 167) adds that “[n]ot only was the construction of Jamaican Jews [...] a separate racial category common in widely circulated writings, such as Edward Long’s History of Jamaica, but it was institutionalized in the colony’s laws and in the island’s racially segregated militias in which Jews were required to participate: whites, Jews, free blacks, and mulattoes each had separate units with ‘white’ officers in charge.”

Labatt’s work is an example of early creole writing, a literary category that began to be recorded in the years immediately following the abolition of slavery. Creole culture has been variously defined. According to Kamau Brathwaite (1974, 6), creolization is a form of cultural expression “divided into two aspects of itself: ac/culturation, which is the yoking (by force and example, deriving from power/prestige) of one culture to another (in this case the enslaved/African to the European); and inter/culturation, which is an unplanned, unstructured but osmotic relationship proceeding from this yoke.” Labatt’s work might be read in light of both processes. His work clearly draws both from English literary forms and Afro-Jamaican rhetorical traditions. And his unique blending of forms might be read as a distinctly Jamaican creole style.

Labatt’s writing appeared within the context of nineteenth-century literary traditions, specifically a form Tim Watson (2008, 17) calls “creole realism” which attempts “to narrate the story of the British colonies from the point of view of a planter class defined by their qualities of reasonableness and enterprise.” Edward Long and Bryan Edwards offer two examples of white creole Jamaican writers who adopted this form. Watson explains, “The documentary record of the Caribbean told from the white creole point of view is forever turning into the literary genres that it eschews, sentimental fiction, gothic melodrama, and imperial romance” (18). Thus, even as this body of writing deploys realist narrative qualities, it also includes other literary forms that would seem to be realism’s opposite. In keeping with this tradition, “Curgy’s Funeral” blends realism and farce, while “An Incident in the Late Rebellion in Jamaica” combines realism and gothicism. Labatt is unusual in his frequent use of English literary forms to question the reasonableness or enterprise of white creole figures.

Candace Ward notes that nineteenth-century white creole writers turned to the novel “to construct and uphold categories of racial difference tending to minimize, ignore, or – importantly – manage the power and persistence of African and black creole influences on West Indian life” (2017, 9). Montgomery; or, the West-Indian Adventurer (1812-13) and Marly; or A Planter’s Life in Jamaica ([Williams] 1828), for example, capture the period of transition in Jamaica from slavery to emancipation. Both of these works offer positive images of white creole culture. One of the unusual and interesting features of Labatt’s work is his keen interest in exploring traditions of Afro-Caribbean cultures. Whereas his contemporaries may have wanted to ignore or overpower African and Black creole culture, as Ward suggests, Labatt remained interested in the way Afro-Caribbean cultures used clever narrative or religious tactics to deceive white characters. Labatt’s stories do not deride or dismiss these tactics; rather, they show how such strategies of resistance granted Afro-Caribbean storytellers power in their encounters with white people.

Labatt’s work is also contextualized by the emergence of imperial romances in the early nineteenth-century Caribbean, which Tim Watson (2008, 12) describes as a kind of proslavery romance or narratives told through a nostalgic lens that semtimentalized slavery as welcome by Black Jamaicans. While Labatt did not sentimentalize slavery, it’s important to remember that he wrote about enslaved people within a culture where such narratives were common. One prominent example, Hamel, the Obeah Man (1827), published anonymously, responds to rising abolitionist tensions and the well-founded fear of the inevitability of emancipation. Hamel thus offers a romantic view of slavery, as Watson (2008, 94) puts it, “a celebration and a valediction of a people whose way of life is about to be consigned to the past, the white planter class of the Caribbean.”

Central to Labatt’s contexts are two popular Jewish Caribbean writers. E.L. Joseph, the Jewish Trinidadian author of Warner Arundell: The Adventures of a Creole (1838) depicts Trinidad in the years following emancipation during, as Ward (113) notes, a period of “confidence in the emancipated Caribbean’s centrality in world affairs.” A few decades later Herbert G. de Lisser appeared on the literary stage. De Lisser was an Afro-Jewish Jamaican who, like Labatt, served as editor of The Daily Gleaner. De Lisser’s well-known novel, The White Witch of Rosehall (1929), suggests a sustained resonance of gothic aesthetics in Jamaican culture. Labatt, in “An Incident in the Late Rebellion in Jamaica,” and de Lisser, in The White Witch of Rose Hall, use gothic tropes to depict the Baptist Rebellion of 1831-32.

“Curgy’s Funeral” and “An Incident in the Late Rebellion in Jamaica” engage with two of the most popular tropes in Jamaican literary culture of this period: rebellion and Obeah. Many of the creole romances from this period would similarly focus on the long history of resistance and rebellion. Early nineteenth-century creole writers were alternately respectful or dismissive of Afro-Caribbean rebellion and Obeah. In some cases, Obeah threatened the power of the planter class to control enslaved people. In other cases, Obeah was imagined as proof of the religious potential of Afro-Jamaicans and therefore provided encouragement for missionary work.

William Earle’s Obi or, The History of Three-Fingered Jack (1800) and Hamel, the Obeah Man (1827) as well as de Lisser’s The White Witch of Rosehall (1929) suggest a powerful legacy of literary interest in Obeah as a form of religious expression and resistance against plantation violence. Labatt’s depictions of Obeah supplement this list by depicting both how enslaved people used Obeah in powerful ways that had the effect of unsettling the planter class. In the case of “Curgy’s Funeral” the plantation owner, Tom Moody, becomes enraged upon learning that he’s been tricked by Curgy’s use of Obeah.

Labatt’s lifespan covered an important period of Jamaican history. Labatt would have been aged nine during the Sam Sharpe Rebellion (1831-32) which helped bring about the end of slavery in 1834. He also lived through the period of Apprenticeship (1834-38) following emancipation. While formerly enslaved people were technically free during the Apprenticeship period, their rights were significantly limited. On 21 February 1848 Labatt married Judith DeCordova, daughter of one of the founders of The Daily Gleaner, a Jamaican periodical still published today. Labatt served as editor of this periodical from 1843-50.

Raphael Dalleo has noted that “during the period of slavery, a small group maintained a monopoly on the written word so that entry into the literary public sphere required patronage, approval, and even translation from the literate elites” (42). Labatt’s position in this world is hard to pin down for certain. The Daily Gleaner, founded by Jamaican Jewish half-brothers Jacob and Joshua DeCordova, first appeared in 1834. The timing of this paper and Labatt’s involvement means that he would have had a mixed audience of readers comprised of wealthy planters and white, bi-racial, and Black members of the working classes, as well as formerly enslaved people. The public sphere in this period was diverse and witnessed a growing body of literary and media outlets that reflected and influenced the rise of literary and print culture. Labatt’s literary output recalls this vibrant cultural history.

Philip Cohen Labatt’s Background

Labatt’s Literary Interests

Labatt’s allusions to and blending of English and Afro-Jamaican literary texts in his oeuvre – short stories, poetry, and drama – demonstrate his interest in a wide range of literary forms and cultural traditions. I. Lawton (1855, v-viii) notes that Labatt was a member of Jamaica’s Literary Society and published writing in several Jamaican periodicals including the short lived periodical, First Fruits of the West (1844). Labatt also started his own literary periodical, The Echo, copies of which no longer exist. Labatt’s primer, Catechism of Jamaica: History and Geography of Jamaica (1848), was used as a textbook in Jamaican schools during the nineteenth century (Arbell 2000, 58). I. Lawton preserved many of Labatt’s literary works in the posthumous collection, Selections from the Miscellaneous Posthumous Works of Philip Cohen Labatt (1855).

Labatt’s Poetry and Drama

Labatt wrote one play, “Next of Kin: Or Who is the Heir? A Farce, in One Act” (1855, 1-18), which was likely never performed on the stage (Hill, 1992, 176). The play is set in London and considers the legacy of an English man’s death in Jamaica. Many of Labatt’s poems draw from English or Irish literary texts. In “The Pleasures of Drink,” Labatt (1855, 48) includes a footnote mentioning “one of Mrs. Hall’s beautiful tales of the Irish peasantry,” recalling the Irish-born Anna Maria Hall (1800-81) who later moved to England. Labatt’s poem, “The Rhyme of the Ancient Planter. Altered from Coleridge” (1855, 80-83), derides English colonialism and slavery through its attack of sugar consumption. These texts suggest that Labatt was familiar with English literary culture and colonial critiques. In “Stanzas. On the Death of the Young,” Labatt (1855, 84-85) writes about the death of a child. Labatt’s own son died young, and thus the poem may be autobiographical.

Labatt’s Short Stories: Slavery and Resistance in Jamaica

While Labatt was born during the period of slavery, many of his narrators speak from the post-emancipation years (i.e., 1834 and onward) as they reconstruct an earlier period of Jamaican violence. This vantage point leads to questions about the extent of Labatt’s critique or complicity with the racial systems he invokes. In “Curgy’s Funeral, Or the Old Time Busha” (1855, 30-35) and “An Incident in the Late Rebellion in Jamaica” (1855, 36-47), Labatt creates narrators who lie outside the institution of slavery. Readers are encouraged to consider how the narrators’ speaking position shapes their treatment of both the attitudes of the masters and depictions of acts of rebellion or resistance by enslaved people.

Jamaica remained a British colony until 1962. Colonial governance continued to privilege white authority long after the emancipation of slavery. Labatt’s respectful emphasis on powerful Black figures in “Curgy’s Funeral” and “An Incident” points to an interest in resistance as a sophisticated performance of Afro-Jamaican culture. It was unusual for a white writer to have such intimate knowledge of Black resistance as early as the 1850s.

Labatt’s focus on the figure of the trickster and Obeah practices are also noteworthy in this respect. In “An Incident,” Labatt depicts a rare contemporary account of the Sam Sharpe Rebellion of 1831-32 and a Queen Nanny character, an eighteenth-century leader long mythologized in Jamaican culture as a heroic warrior. Labatt’s possibly autobiographical story, “Some Passages in the Life of Charles Dacre Heblin, A Rebel” (1855, 50-67), depicts the life of a bi-racial child faced with the limits of legal restrictions against free Blacks in Jamaica. The dearth of written accounts from this period about the Sharpe Rebellion, Queen Nanny, and questions about Labatt’s racial identity and relationship to his subject matter makes this story remarkable.

The Literary Contexts for “Curgy’s Funeral”

Labatt’s work was well-known at the time of his death in 1854. Lawton collected materials, probably from periodicals that no longer survive. It’s therefore often difficult to determine the exact publication year of Labatt’s individual works. “Curgy’s Funeral, Or the Old Time Busha” (Labatt 1855, 30-35) is one of many texts published posthumously in 1855 in Lawton’s edition of Labatt’s work and now republished by One More Voice in a critically-edited version. “Curgy’s Funeral” tells the story of Curgy and Caesar, two enslaved people living on Tom Moody’s plantation. A narrator named Joe details different forms of resistance used commonly on plantations throughout the Atlantic world. The story preserves rare written accounts of the ways enslaved people performed resistance to the institution of slavery and masters through sophisticated adaptations of cultural traditions.

Obeah and Poison

Obeah, a belief system referenced in “Curgy’s Funeral,” is drawn from multiple regions in Africa. It has long been part of Caribbean culture and is well represented in literary texts. Nicole Aljoe (2012, 136) explains that Obeah has a complex definition: “During the plantation era, stories abounded about slaves who could cast spells and commune with the spirits.” Dianne M. Stewart (2005, 42) adds that Obeah wasn’t just a form of religious expression. It enabled the enslaved “to exercise control over other people and invisible forces, functioning thus as a form of social control and as a system for checking and balancing power and authority in enslaved African communities where personal disputes were censored.”

During the nineteenth century, Obeah was known to white planters but was not well understood. Indeed, the aura of mystery was part of Obeah’s power. People who were enslaved could practice Obeah without the masters’ full understanding of their actions. According to Eugenia O’Neal (2020, 5), “the Obeah man or woman was a healer as well as a person who commanded the allegiance of spirits.” When Curgy announces that he speaks with his dead grandfather, he’s signaling his knowledge of Obeah (Labatt 1855, 31). When Tom Moody and Joe, the story’s narrator, laugh in confusion at Curgy’s expression of his beliefs, the narrator suggests that Curgy has succeeded in practicing uncensored cultural rituals that the white men are unable to decode (Labatt 1855, 31).

In the story’s conclusion Joe refers to the narrative as a farce, suggesting that we cannot necessarily read it face value. Labatt may be constructing Curgy’s practice of Obeah to emphasize the white men’s (Tom and Joe’s) ignorance of their own limited knowledge of Afro-Jamaican religious culture. We might also read Labatt’s depiction of Obeah as a vehicle for underscoring Curgy’s power over both the master and the storyteller. Read this way, readers might consider how the unreliable narrator presents both Curgy’s trickery and Caesar’s sly chuckling.

Tom Moody, the plantation owner in “Curgy’s Funeral,” poisons Curgy with ipecacuanha wine. While not technically a poison, the emetic tortures Curgy. This event recalls a prominent fear among members of the plantocracy concerning the threat of poisoning by enslaved people. Scholars have noted many examples of successful and alleged acts of poisoning (Savage, 2012, 149-71). Readers might wonder why Tom Moody, the master of the plantation, would need to affirm his power in the first place. But his choice of poison as a means of exerting control recalls the very danger many plantation owners feared.

Signifying

In “Curgy’s Funeral,” Labatt presents an example of what Henry Louis Gates (1988, 51) calls “[t]ales of the Signifying Monkey,” which, he adds, “seem to have had their origins in slavery.” Gates explains that the Signifying Monkey is “the ironic reversal of a received racist image of the black as simianlike, the Signifying Monkey, he who dwells at the margins of discourse, ever punning, ever troping, ever embodying the ambiguities of the language, is our trope for repetition and revision” (52). Labatt depicts some of the ways that enslaved people turned racist images on their head or deployed racist stereotypes to resist the authority of those who use and create them. The repetitions, reversals, and slipperiness of language in this story can be read as expressions of signifying.

Labatt calls into question the interpretive instability of the writing on the master’s paper documents as well as acts of resistance by enslaved characters. Indeed, the written word in “Curgy’s Funeral” is repeatedly caught up in a system of play and deferral of meaning. This reflects Gates’ (1998, 55) point that

the Signifying Monkey invariably repeats to his friend, the Lion, some insult purportedly generated by their mutual friend, the Elephant. The Monkey, however, speaks figuratively. The Lion, indignant and outraged, demands an apology of the Elephant, who refuses and then trounces the Lion. The Lion, realizing that his mistake was to take the Monkey literally, returns to trounce the Monkey. It is this relationship between the literal and the figurative, and the dire consequences of their confusion, which is the most striking repeated element of these tales. The Monkey’s trick depends on the Lion’s inability to mediate between these two poles of signification, of meaning.

In Labatt’s story, the enslaved Caesar’s “low sly chuckle” and disclosure of a secret leads the master, Tom Moody, to a state of rage. The master, in turn, seeks revenge on Curgy, another enslaved character, by an act Tom describes as paying him “in his own coin” (Labatt 1855, 32) or what modern readers might paraphrase as giving Curgy a taste of his own medicine. The master never returns to “trounce the Monkey” (to use Gates’s words) perhaps because Tom fails to see how he’s been played by Caesar. The events in Labatt’s story recall Gates’s description of an important form of trickster tactics with ties to west African storytelling traditions. Labatt’s example is one of the earliest to appear in writing.

While “Curgy’s Funeral” may lead contemporary readers to sympathize with Curgy, the victim of the master’s violence, readers might also see Caesar as quietly successful in controlling the master. In particular, Caesar uses acts of sly subterfuge to elicit Tom’s rage. The master’s trickery – which mirrors the trickery in his enslaved workers – extends the series of manipulations along with the narrator’s choice to call his tale a farce, thereby reframing the plot within an English literary tradition that uses humor as a form of social critique.

It’s difficult to know who or what Labatt critiques in this farce. Does Labatt celebrate the subtle and powerful methods deployed by the enslaved to resist Tom, the plantation owner? And whose trickery does Labatt endorse, celebrate, or critique: Curgy’s subterfuge; Caesar’s ability to unsettle Tom; or Tom’s use of poison to trick his enslaved workers? Perhaps Labatt suggests cultural parallels by depicting all three methods of trickery?

In “Curgy’s Funeral,” Labatt’s enslaved characters speak in a language that the white men cannot understand. Labatt’s depiction of Jamaican creole language helps to underscore Curgy’s ability to speak publicly without being understood. The story’s narrator, Joe, describes an instance of when he, Curgy, “entered into a long rambling explanation, half of which was Greek to me, of his having seen the ‘perit’ of his ‘grandy’ and of his having been warned by it of his approaching death. The result of this lachrymose take was a hearty roar of laughter from his master and myself” (31). In such moments, Labatt reminds readers that neither the plantation owner nor the storyteller understand the language of the enslaved.

Jean D’Costa and Barbara Lalla (1989, 5) note that fears of slave rebellions frequently “drove the planters to uproot and destroy the language and the customs of their new slaves. The Europeans were well aware that the incomprehensible tongues of their reluctant property could be the means of subversive communication.” The creole language that emerged in its wake by the mid-eighteenth century, D’Costa and Lalla (6) add, was a necessary creation for the plantation” in allowing newly arrived enslaved people to communicate with people using different languages. Curgy’s creolized language might be read as an example of Labatt’s adoption of realist writing. Not only does Labatt include a Black vernacular discourse, but, importantly, he depicts a moment on the plantation when the white planter and the story’s narrator cannot interpret the enslaved character. While they make fun of Curgy, Labatt simultaneously suggests that his narrator is attempting to depict a culture illegible to him.

Tom’s response to Curgy to “go about his business, and to take care that he was after no tricks” (31) signals the tension at the heart of the story. The fact that the first mention of tricksterism appears at a moment when the white men cannot understand Curgy’s language suggests, moreover, that Labatt has not only created an unreliable narrator, but that Black vernacular speech is at the root of Curgy’s trickster tactics. If readers of the story believe the narrator is unreliable, they might consider how Labatt presents language’s uses as a form of trickery that flew under the radar of the white men who control plantation overseers and those who control narratives of plantation life.

By the 1830s, enslaved Jamaicans outnumbered white planters ten to one. Rebellions were instrumental in bringing about slavery’s demise. Jamaica experienced two major rebellions prior to the publication of Labatt’s collection of writing: Tacky’s Revolt in 1760 and Sam Sharpe’s Rebellion in 1831-32. Tom Moody’s rage, fear, and insecurity about his diminishing power on the eve of abolition can be read within the context of a longer history of rebellion and Black resistance that led to a powerful abolitionist movement.

The Literary Contexts for “An Incident in the Late Rebellion in Jamaica”

Labatt’s story “An Incident in the Late Rebellion in Jamaica” (1855, 36-47), now also republished by One More Voice in a critically-edited version, is set during the Sam Sharpe Rebellion (1831-32). The abolitionist movement worked during the preceding decades to lay the groundwork for the emancipation of slaves. The Sharpe Rebellion was the final catalyst that ended slavery in Jamaica. Very few literary accounts of this important Rebellion were written by eye-witnesses. Although Labatt would have been young at the time of the event – age 9 – it’s possible his story draws either from memory and/or stories he was told.

Queen Nanny

“An Incident” presents an early example of Queen Nanny, the eighteenth-century Maroon warrior. The Maroons – a group made up of indigenous Taino people, free Blacks, and people formerly enslaved by the Spanish – lived in the interior of Jamaica. Queen Nanny led the Windward Maroons through a successful battle against the British in the First Maroon War (1728-40). Steeped in legend, stories about Queen Nanny emphasize her super-human strength and reputation as a universal mother figure who upholds African traditions in Jamaica. Labatt’s narrator refers to the visitor in his camp as “mother” or “good mother.” Her voice is described as “strikingly devoid of the negro patois” signaling her distinction from Afro-Jamaicans (Labatt 1855, 37). Also noteworthy is Labatt’s portrayal of the old woman’s “long white teeth protruding from her gums” and the fact that she’s carrying a knife (37). Stories about Nanny often celebrate her status as a great leader and warrior. Here Labatt builds on those traditions while using a gothic aesthetic as a sign of her supernatural powers.

According to Karla Gottlieb (2000, xiv), Queen Nanny is “perhaps the most significant figure in the history of the Jamaican Maroon struggle for freedom. [...] In 1976, she was made a national hero of Jamaica.” British writers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries frequently depicted Queen Nanny in a negative light. Readers might consider whether Labatt celebrates or derides the Queen Nanny figure of the story. Do Labatt’s depictions of her uncertain end and fearless leadership endorse legends focused on her nobility and strength?

It’s noteworthy that the old woman gains authority among the soldiers in the story when she narrates events from her own life. Her prompting is Toosy’s act of singing the song “Alice Gray” (Philip, qtd. in Labatt 1855, 38-39). This song, composed around 1830 by Mrs. Millard Philip, shared a title with a novel by Catherine George published in 1833. When the old woman tells her own story about Alice Gray, the white child she claims to have raised, she reframes the English cultural allusion within a Jamaican context (Labatt 1855, 41-42). The old woman’s spoken narration about a white child named Alice Gray appears to be a ploy to bring the soldiers under her spell. Moreover, the reference to this popular cultural reference suggests Nanny’s familiarity with English culture and may provide evidence of her powers of manipulation as she leads the men into battle.

Labatt’s Gothic Rebellion

Labatt interlaces Nanny’s reputation as a powerful leader with an English gothic aesthetic. Labatt draws a particular connection with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). The “old woman,” as she is called in “An Incident,” has qualities that align her with both Victor Frankenstein and his offspring. Like Shelley’s novel that includes an interior narrative by the creature, Labatt breaks with the plot of the battle to allow room for the old woman’s narration of her own tragic life.

Both Shelley’s creature and Labatt’s old woman are also imagined as having deformed bodies. Labatt’s narrator (Labatt 1855, 37) describes the old woman in quite racist terms, as “a tall gaunt negress” whose “lower lip hung down so low, as almost to conceal her chin, whilst five or six long white teeth protruding from her gums, gave her an appearance of ghastliness and terror, which struck a chill to our hearts.” Such language plays to stereotypical, nineteenth-century caricatures of Black individuals. Readers familiar with Frankenstein might also see parallels in Labatt’s rendering of treacherous Jamaican mountains and Shelley’s depictions of terror-inducing Alps.

Labatt’s Nanny figure details the story of her son who murders Alice, the child of her mistress. She explains, Alice “died within an hour in my arms, but not before she informed me, in a temporary resuscitation of her faculties, that her former play-fellow and servant—my son, the monster to whom I had given birth, was the heartless wretch who had wrought her ruin” (Labatt 1855, 42). Again, Labatt seems to adapt Frankenstein to include both a sexualized white woman in danger of a predator and a woman depicted in racialized terms as having a “gigantic size” with “nostrils dilated” who is both monstrous looking and a creator of murderers (43). In the construction of this single character, Labatt unites the mother of a murderer with Frankenstein while using racially-charged language to align her abject body with Frankenstein’s offspring’s body.

Conclusion

Labatt’s “An Incident in the Late Rebellion in Jamaica” offers an important early example of creolized storytelling in its blending of Afro-Jamaican heroes and English soldiers to describe Jamaican historical events. The story’s setting in an actual Rebellion points to Labatt’s continued interest in a longstanding Jamaican tradition of rebellion and resistance. While “Curgy’s Funeral” and “An Incident” draw from distinct references (respectively, a plantation culture of resistance and rebellion stories), both texts are rooted in shared folkloric traditions, narrative techniques, and performative traditions central to the formation of Jamaican creole culture.

Works Cited/Further Reading

Aljoe, Nicole. 2012. Creole Testimonies: Slave Narratives from the British West Indies, 1709-1838. New York: Palgrave.

Anonymous. 1812. Montgomery; or, the West-Indian Adventurer. 3 vols. Kingston, Jamaica: Offices of the Kingston Chronicle. Originally published 1812-13.

Anonymous. 1828. Marly, or A Planter’s Life in Jamaica. Glasgow: Richard Griffin & Co.

Arbell, Mordechai. 2000. The Portuguese Jews of Jamaica. Kingston: University of West Indies.

Barringer, Tim, and Wayne Modest, eds. 2018. Victorian Jamaica. Durham: Duke University Press.

Brathwaite, Kamau. 1974. Contradictory Omens: Cultural Diversity and Integration in the Caribbean. Mona, Jamaica: Savacou.

Dalleo, Raphael. 2011. Caribbean Literature and the Public Sphere: From the Plantation to the Postcolonial. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

D’Costa, Jean. 1989. Voices in Exile: Jamaican Texts of the 18th and 19th Centuries. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama.

De Lisser, Herbert George. 1929. The White Witch of Rose Hall. London: Ernest Benn Limited.

Earle, William. 1800. Obi; or, The History of Three-Fingered Jack. London: Earle and Hemet.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. 1988. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

George, Catherine. 1833. Alice Gray: A Domestic Novel. London: Newman.

Gerber, Jane S. 2014. The Jews in the Caribbean. Edited by Jane S. Gerber. Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

Gottlieb, Karla. 1992. “The Mother Of Us All”: A History of Queen Nanny Leader of the Windward Jamaican Maroons. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, Inc.

Hill, Errol. 1992. The Jamaican Stage 1655-1900: Profile of a Colonial Theatre. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Joseph, E.L. 1838. Warner Arundell: The Adventures of a Creole. London: Saunders and Otley.

Kaufman, Heidi. 2019. “Jamaican Jewish Tricksters: Philip Cohen Labatt’s Literary Crossings.” In Caribbean Jewish Crossings: Literary History and Creative Practice, edited by Sarah Phillips Casteel and Heidi Kaufman, 66–88. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Kriz, Kay Dian. 2007. “‘Belisario’s “Kingston’s Cries” and the Refinement of Jewish Identity in the Late 1830s.’” In Art and Emancipation in Jamaica: Isaac Mendes Belisario and His Worlds, edited by Tim Barringer, Gillian Forrester, and Barbara Martinez-Ruiz, 163–78. New Haven, CT: Yale Center for British Art.

Labatt, Philip Cohen. 1855. Selections from The Miscellaneous Posthumous Works of Philip Cohen Labatt In Prose and Verse. Edited by I. Lawton. Kingston, Jamaica: E. J. DeCordova.

Millard, Mrs. Philip. 1833. “Alice Gray: A Ballad.” London: A. Pettet.

O’Neal, Eugenia. 2020. Obeah, Race and Racism: Caribbean Witchcraft in the English Imagination. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press.

Savage, John. 2012. “‘Slave Poison/Slave Medicine: The Persistence of Obeah in Early Nineteenth- Century Martinique.’” In Obeah and Other Powers: The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing, edited by Diana Paton and Maarit Forde, 149–71. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Shelley, Mary. 2012. Frankenstein. Edited by D.L. Macdonald and Kathleen Scherf. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press.

Stewart, Dianne M. 2005. Three Eyes for the Journey: African Dimensions of the Jamaican Religious Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ward, Candace. 2017. Crossing the Line: Early Creole Novels and Anglophone Caribbean Culture in the Age of Emancipation. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Watson, Tim. 2008. Caribbean Culture and British Fiction in the Atlantic World 1780-1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[Williams, Cynric R.]. 1827. Hamel, the Obeah Man. London: Hunt and Clarke.