“Africa Considered in its Social and Political Condition [...]”

Digital Publication DetailsSource Book Details

BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press

Please turn your mobile device to landscape or widen your browser window for optimal viewing of this archival document.

AFRICA CONSIDERED

IN ITS

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL CONDITION

WITH

A PLAN

FOR THE

AMELIORATION OF ITS INHABITANTS.

BY A NATIVE OF DARFOUR,

CENTRAL AFRICA,

AND ORIGINALLY A SLAVE.

ENTERED AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

PRICE THREEPENCE.

![Title page for Africa Considered in its Social and Political Condition [...].](/img/bipoc-voices/liv_025997_0002_deriv-586px.jpg)

PREFACE.

I have always labored under the idea that man likes to hear the adventures of his fellow man, and, actuated by that impulse, I will relate a brief account of my history before laying down my plan for the amelioration of my native country.

SELIM AGA.

London, May, 1853.

![Preface for Africa Considered in its Social and Political Condition [...] with British Museum stamp.](/img/bipoc-voices/liv_025997_0003_deriv-586px.jpg)

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE AUTHOR.

SURROUNDED by some beautiful mountain scenery, and situated between Darfur and Abyssinia, 2,000 miles in the interior of Africa, is a small valley going by the name of Tegla. To that valley I stretch forth my affections, giving it the endearing appellation of my native home and fatherland. It was there that I was born—it was there that I received the fond looks of a loving mother—and it was there that I set my feet, for the first time, upon a world full of cares, trials, difficulties, and dangers.

My father being a farmer, I used to be sent out to take care of his goats. This service I did when I was between seven and eight years of age.

As I was the eldest of the boys, my pride was raised to no small degree when I beheld my father preparing a farm for me. This event filled mind with the grand anticipation of leaving the care of the goats to my brother, who was then beginning to work a little.

While my father was making these preparations, I had the constant charge of the goats, and being accompanied by two other boys, who resided near my father's house, we wandered many miles from home, by which means we acquired a knowledge of the different districts of our country. It was while in these rambles with my companions that I became the victim of the slaveholder.

While tending our goats between two hills, we espied two men shaping their course towards us. They enquired whether we had any goats for them (a question quite common in my country). Our reply was, of course, in the negative; but they merely used this craft to deprive us of suspicion.

Myself being nearest to them, I was firmly secured in their hands, and forced away, whether I would or not. On showing symptoms of resistance, one of them procured a green twig, and whipped me till the blood was falling in drops from my legs. After proceeding some miles, we came to a house, where I was tied with ropes, hands and feet, and laid down to rest on the bare ground.

Next morning, before dawn of day, my cruel master took the ropes off my legs, and, pointing to me a certain direction, desired me to walk, while he followed with a large whip. Terrified out of my judgment, I saw that there was nothing to be done but either do or suffer. I of course chose the former. This was rather harsh treatment for a child of about eight years of age. I was driven like a pig into the village of Tegla, where my inhuman master sold me to an Arab.

On entering the house of my new master, what was my astonishment on seeing an old acquaintance there, a girl with whom I had an interview a few weeks previously. This girl, whose name was Medina, admonished me on this occasion, telling me to do whatever I was desired, assuring me that the white man would not care for taking our lives—that the killing of us would not cost him a thought. We were firmly secured with iron chains on our feet, and were never permitted to go far from the house. We could never fall upon plans for effecting our escape, although we often tried means for that purpose.

One night I managed to get the chains off my feet, and would have escaped, had not the fear of being recaptured prevented me.

A short time after this a caravan, consisting of merchants and travellers, left the village of Tegla. With this caravan our master joined, and after a day's journey we came to a small village, where he was disappointed in his object, viz., the disposing of us into another's hands; therefore he had no other recourse but to return to his own country.

Arriving at Tegla, we received the heartrending intelligence that our friends had been in search of us, and were frustrated, having heard that we were taken to a distant land.

Another caravan was soon equipped for a further distance. This was some four days' journey from the village of Tegla, to a large town called Kordofan, which is under the jurisdiction of the Pacha of Egypt. The first night we pitched our tents at a well of water, not having seen a single house on the whole of our journey. The next day we continued our journey till late at night, when we received the guidance of some light from a distant village, where we arrived and reposed ourselves. We stayed a few days at this place, and shared the unfeigned hospitality of the people who were uncommonly kind.

During our stay here, Medina and I were taken to the camp of the Turks, not far from the village, where we were put through different exercises. The first thing we were desired to do was to show our tongues, and then our teeth. The rest of our limbs underwent a serious examination also.

The next morning our master joined the Turks, who were returning to Kordofan, and by that means insured our fate of never returning to our dear native country.

In two days we reached the point of our destination, and there our master sold us to another Arab, with whom we lived but two or three days. From an Arab we fell into the hands of a Turk, one of the most cruel men in existence. Being a captain in the Egyptian army, his men suffered many harsh cruelties under him.

On one occasion a soldier having been brought to his house for a small offence, he took the office of corporal, and commanding four men to hold him down, beat the poor man till the blood was running from his cheeks. The keeper of his camels often suffered in a similar way. The duties of waiting at table, washing dishes, making coffee, and waiting for orders were allotted to me as my share of the work. To mention all the cruelties I suffered at that time would be quite needless. My master, who was a great monster of cruelty, punished every small fault with great severity. At one time, having been sent on an errand by his lady without his permission, he met me on my return, and beat me about the head till the blood was running out of my ears. At another time, having made some coffee by his own orders, I happened to make a few cups more than was required. He said nothing at the time, but after I was in bed and asleep, he got hold of a horse whip, and coming upon me unawares, thrashed me till I was quite speechless.

From Kordofan I was brought down to Dongola and Korti, in Nubia, and from thence down the Nile to Cairo, and after having been sold and re-sold nine times, I came into the hands of Mr. Thurburn, British Commercial Consul in Egypt, with whom I came to England about the middle of the year 1836.

The Consul left me under the care of his brother, John Thurburn, Esq., of Murtle, Aberdeenshire, North Britain, by whom I was sent to school, and under his kind auspices I received a liberal English education, travelled with him through many parts of the world, and at last, wishing to establish commercial intercourse between Great Britain and my native country, with the view of putting an end to the Slave Trade, I left him, in 1849, and came up to London to lay my plans before the Government, but being a stranger I met with many difficulties, and was obliged to take an engagement at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, where I lectured on the Panorama of the Nile for nearly twelve months. On the 14th of August, 1851, I wrote a letter to Her Majesty's Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, and received the following answer:—

"Mr. Addington presents his compliments to Selim Aga, and wishes to see him on the subject of his letter of the 14th instant to Lord Palmerston. If Selim Aga can call at the Foreign Office on Thursday, the 28th instant, at 3 o'clock, or between 3 and 4 on the afternoon of that day, Mr. Addington will be happy to receive him.

"Foreign Office, 26th August, 1851.''

I waited on Her Majesty's Secretary, and explained my views, but as the Government has been in a state of disquietude, nothing has as yet been done.

Although frustrated in this my main object, I still hope to be of some use to my countrymen, and therefore content myself by saying as the late Mehemet Ali said, "Allah cherib, God is merciful; He will in his good time, and in his own way, open a thoroughfare by which the African will walk to the heights of civilization, and arrive at that blessed elevation where he will enjoy that social, that religious, and that rational liberty which is due to every nation, every society, and every individual." I have shed tears of joy and gratification while thinking of the kindness of the inhabitants of the United Kingdom towards my countrymen. No person can say that those Africans who have conducted themselves with propriety have not been cordially received by every Englishman, Irishman, or Scotchman. In the British dominions the same protection is held out to every individual, no matter about his colour or clime; and the African, despised and degraded in other countries, is looked upon by every British subject as "a man and a brother."

Permit me, then, to submit the following plan for the amelioration of my countrymen for your perusal, being fully persuaded that Africa possesses sufficient wealth to repay any philanthropist who may be disposed to assist its inhabitants to extricate themselves from the lion grasp of ignorance.

Africa may be divided into three parts—the northern division, chiefly inhabited by Arabs and Turks, the centre by negroes, and the southern portion by Hottentots and Caffres. Nearly the whole of the country is divided into petty principalities, the supreme power being vested in the hands of a Prince or native Chief, who possesses absolute power. For about three hundred years Africa has been depopulated of its inhabitants by a traffic in human beings, well known as the Slave-trade, a system in itself degrading and illegitimate. God created man, and gave him power over the inferior animals; but man has delighted, and still delights to debase his fellow-man, and to bring him on a level with the brute creation. Let those who still persevere in carrying on this man-degrading traffic take warning, lest at the coming Judgment they receive the fearful reward which awaits them—the wrath and curse of the Omnipotent.

The traffic in human flesh has kept the Africans in ignorance, barbarity, and social degradation; and, although Great Britain is doing a great deal to annihilate that horrid system, yet it will never be finally stopped until the Africans are educated, and their habits changed from their present warlike aspect to a quiet and peaceful state.

As there is nothing impossible in the 19th century, such a change could be effected in about twenty years.

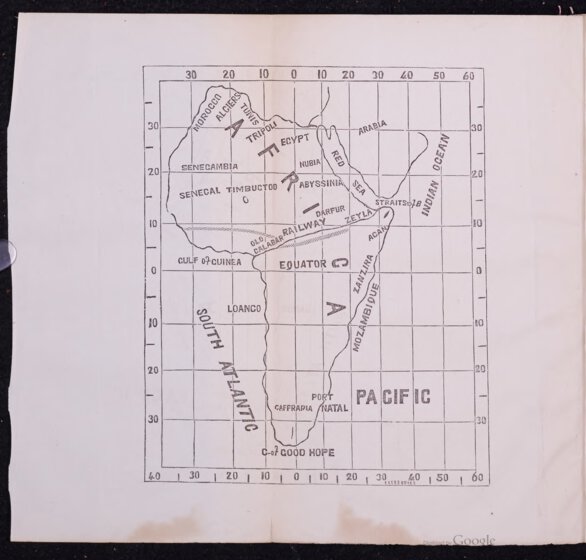

The plan is simply this:—Establish a Railway across the whole continent of Africa, from east to west, and introduce Christianity in connection with commerce into the country, and you will at once give the Africans an opportunity of seeing what a nation can derive through the influence of the Christian religion. A Railway formed across Africa from Zeyla on the Straits of Bab-el-Mandel to Old Calabar, on the Gulf of Guinea, will secure the trade of China, the East Indian Archipelago, India, Ceylon, and Arabia. It will save a sea voyage of seven thousand miles round the Cape of Good Hope, and afford to the inhabitants of Africa an opportunity of becoming acquainted with the customs of civilised nations, and ultimately become through this voluntary process a rational, an intelligent, and an industrious community.

Imagine to yourself the pleasing prospect of seeing the inhabitants of Galla, Abyssinia, Darfur, Bornou, Houssa, and of the Eboe countries, crowding to their respective Railway Stations to exchange the natural products of Africa, such as cotton, indigo, palm oil, ivory, and dyewoods, for Manchester prints and British cutlery.

As Central Africa may be considered the headquarters of ignorance and superstition, an idea will naturally suggest itself to the reader that the educating of its inhabitants will be a key to the civilization of the whole world.

This plan would even become beneficial to emigrants going to Australia, for they could effect their transit in six weeks instead of four months. The passage by railway across the continent of Africa would only occupy three and one-third days; the saving of two months and a half fully repaying the emigrant for the trouble of disembarking at the Gulf of Guinea, and re-embarking on the Straits of Bab-en-Mandel, for Sydney and Melbourne, through Torres Straits.

I need not mention anything relative to the political benefit which the above scheme holds forth to certain countries; but the sequel is this pleasing consideration—Africa will be civilized; Christianity will rise on the ruins of Paganism; universal freedom will be exchanged for absolute slavery; commerce and industry for indolence; knowledge for ignorance; peace and unity, for strife and war; and intelligence for bestial stupidity. Thus the Africans will become so educated and refined, and their minds so invigorated with truth, literature, and science, that they will daily arise esteemed and admired in the scale of nations, ultimately securing a position in the world, and demanding that national respect which is due to all mankind.

AFRICAN AMELIORATION SOCIETY,

ESTABLISHED FOR THE

CULTIVATION OF FREE GROWN COTTON,

JUNE, 1853

SUBSCRIPTIONS RECEIVED BY SELIM AGA,

11, BREWER STREET, GOLDEN SQUARE, LONDON,

OR AT THE

PANORAMA OF THE SLAVE TRADE.

1 JY 53

John K. Chapman and Company, 5 Shoe-lane, and Peterborough-court, Fleet-street.

Digital Publication Details

Title: “Africa Considered in its Social and Political Condition [...]”

Subtitle(s): “[...] With a Plan for the Amelioration of Its Inhabitants”

Creator(s): Selim Aga

Publication date: (1853) 2022

Digital publishers: One More Voice, COVE

Critical encoding: Thomas Coughlin, Kenneth C. Crowell, Adrian S. Wisnicki

One More Voice identifier: liv_025997

Cite (Chicago Author-Date): Selim Aga. (1853) 2022. “Africa Considered in its Social and Political Condition [...].” Edited by Thomas Coughlin and Kenneth C. Crowell. In “BIPOC Voices,” One More Voice, solidarity edition; Collaborative Organization for Virtual Education (COVE). https://onemorevoice.org/html/bipoc-voices/additional-texts/liv_025997_HTML.html.

Rights: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Accessibility: One More Voice digital facsimiles approximate the textual, structural, and material features of original documents. However, because such features may reduce accessibility, each facsimile allows users to toggle such features on and off as needed.