Metadata

Special Collections, SOAS Library: Google Sheets (view) | ZIP (download)

Adam Matthew Digital (AMD): Google Sheets (view) | ZIP (download)

Zotero (SOAS and AMD): Online Library (browse)

Documentation

The “BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press” project (2021-22) engages with a series of pieces by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) creators that we have identified and documented in the periodicals held by Special Collections, SOAS Library and, separately, the periodical holdings of Adam Matthew Digital. This essay discusses the process by which our project created its metadata and the many considerations involved in the process.

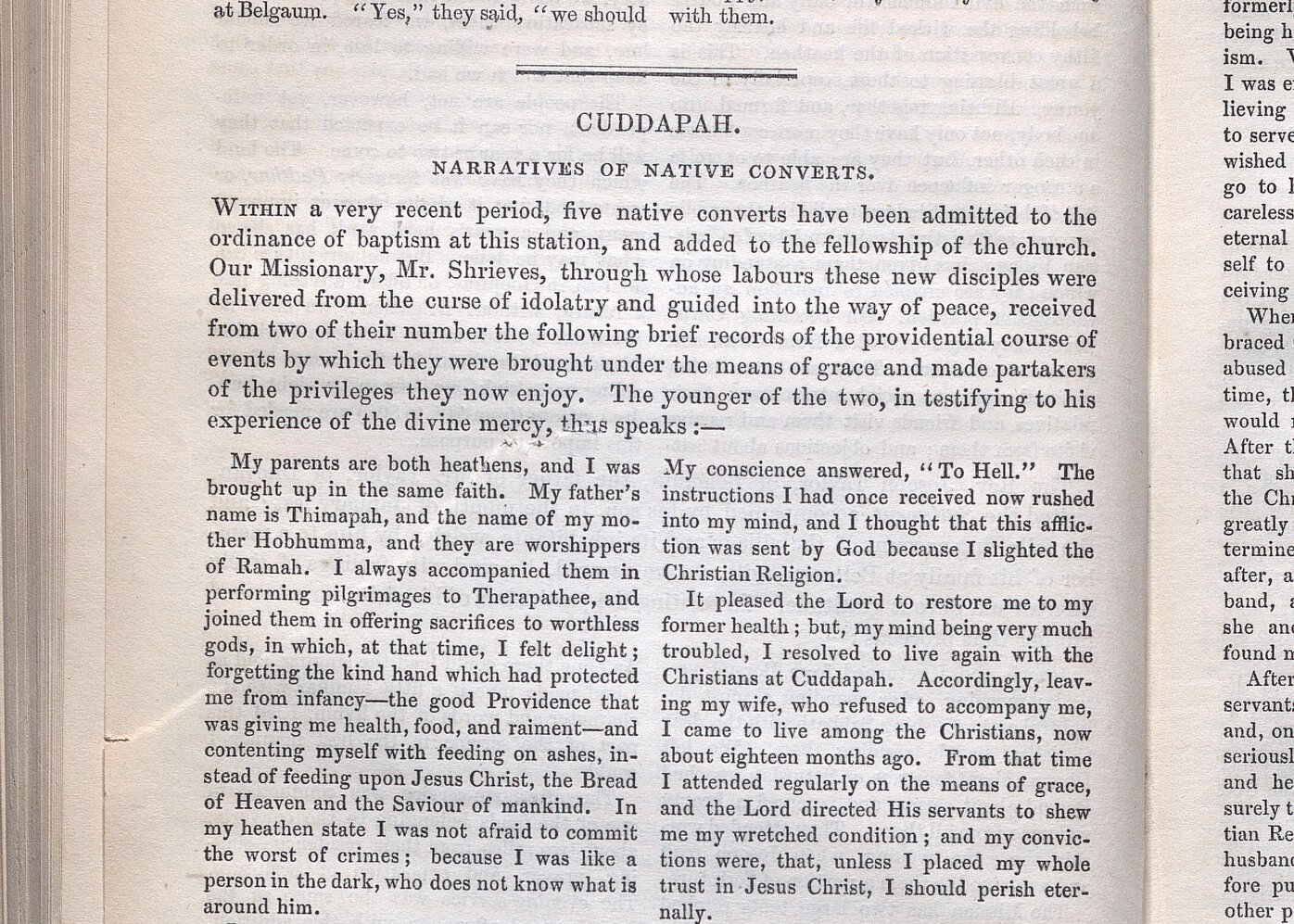

As we note elsewhere (PDF | Word) in more detail, Victorian periodicals do not consistently attribute the work of BIPOC creators. Sometimes the periodicals carry the equivalent of a byline and thus identify the names of the creators. Sometimes a relevant piece begins with a short segment (often anonymously authored) which identifies the given BIPOC creator by name. Sometimes a piece identifies the BIPOC creator only by racial or ethnic characteristics rather than a specific name. Sometimes only the title of a piece indicates the role of a BIPOC creator in writing the piece.

The variety among and within these periodical attribution strategies suggests that programmers will not be able to automate a process for identifying relevant BIPOC creators. Rather, scholars and others with appropriate training must make each such attribution manually, after review, reflection, and consideration of the piece within the context of the given periodical.

In short, there is no way to find and document these voices without actively reading the articles. Even then, it is not always clear if the voices one is reading are by BIPOC creators since the periodicals do not always designate the pieces as such. Since many BIPOC creators adopted British names after baptism, one cannot always tell from the name alone. Articles that list BIPOC creators or occasional articles that offer biographies of BIPOC individuals can help but, again, require that scholars read the originals and make note of the names and other details.

On the one hand, the BIPOC voices have remained hidden because existing metadata for the periodical pieces does not include “voices” that are quoted or otherwise embedded in these texts; on the other hand, recovery work, such as that undertaken by our project, must proceed carefully since these voices have been so heavily mediated by British authors and editors, often across multiple levels: e.g., the local missionary (BIPOC or British) sending someone’s words or texts to a periodical where the editors and writers then mediate the material yet further. The wording of relevant pieces often suggests that missionary periodical editors and others reduced or otherwise curtailed the textual control of BIPOC creators considerably. Relevant pieces thus often advance ideas that diminish the BIPOC individuals who are speaking and/or their cultures. The pieces clearly reflect British imperial and colonial ideologies of the time rather than the actual perspectives of the BIPOC creators.

In creating our metadata, we have simultaneously 1) provided information about the original authorship when we are dealing with material quoting or otherwise including BIPOC voices; and 2) identified the layers of mediation that bring the BIPOC voices to final publication in these missionary periodicals, including (in square brackets) possible additional layers of mediation that can be gleaned by reading the original. So, for example, in one representative case – one of many that might be cited – we provide the following authorship metadata: “Anonymous; [W. Clarkson]; Gungaram.” In this case, the periodical piece only identifies the BIPOC creator as Gungaram; the context of the periodical piece, however, suggests that the voice of this creator went through a series of possible mediations to reach its final published form.

In identifying and documenting pieces involving BIPOC creators for our project, our work went through a four-stage process. In the first stage, Joanne Ruth Davis (SOAS print periodical holdings) or Cassie Fletcher (AMD digital periodical holdings) went through the relevant periodicals page by page to identify pieces that involved BIPOC creators. The work also involved photographing the pieces (Davis) or taking screenshots of them (Fletcher) and creating an initial version of the metadata. In the second stage, Adrian S. Wisnicki reviewed the work of Davis and Fletcher by 1) checking all the images to ensure that each item imaged was complete and in sequence, 2) renaming all image files to the One More Voice file naming standard, and 3) checking the existing metadata against the images. In the final stage, Dino Franco Felluga reviewed the existing metadata, made corrections, and, in consultation with Wisnicki, established new standards for the metadata, with the goal of clarifying various layers of mediation.

Our metadata thus went through a careful process of development. The metadata also makes a significant critical intervention as it represents one of the first instances, to our knowledge, of identifying the work of BIPOC creators in Victorian missionary periodical press at this scale, while also taking account of all the layers of mediation involved in the process.