“The Outcast from China Brought Safely Home”

Digital Publication DetailsSource Article Details

BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press

Please turn your mobile device to landscape or widen your browser window for optimal viewing of this archival document.

THE OUTCAST FROM CHINA BROUGHT SAFELY HOME.

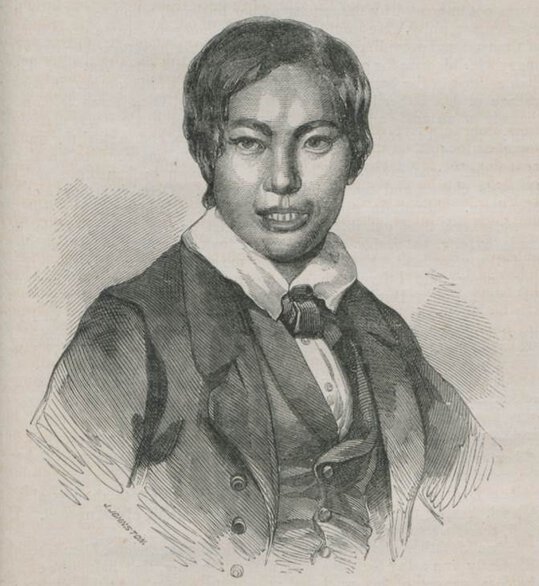

BELOW is the portrait of a Chinese youth, John Dennis Blonde, who died at Ashcroft, near Wentworth in Yorkshire, in the beginning of last year. He is one of the few from amongst that numerous people, who, so far as our knowledge extends, having received the Truth in the love of it, have gone to sleep "in sure and certain hope of the resurrection of eternal life, through our Lord Jesus Christ."

His history is very affecting and intersting, manifesting as it does the tender merch of God towards this poor youth, "When my father and my mother forsake me, then the Lord will take me up." Of this history, which was published at large in the well-known "little green book," the "Church Missionary Juvenile Instructor,"* we can introduce only a brief summary. The following extract, chiefly in Dennis's own words, gives an account of his early life in China, and how it happened that he came to England—

His father was a fisherman at Shanghai: he had a brother who was some years older than himself, who was always very kind to him, but his father was cruel. His poor mother died when he was quite young. She appears not to have had good health some time before her death, and it was not improved by the cruelty of her husband, who used to beat her most unmercifully. He would go a-fishing, and stay away a great length of time without providing for his family; and when he returned he was very angry with his wife for getting into debt, and would often beat her. They then resided in the country; but after the death of his mother, in consequence of his father being so much from home, Dennis was left under the care of an uncle and aunt at Shanghai. This uncle "was a wicked man:" he used to rob the poor boy of his clothes, and to steal the money which was given to pay for his schooling. On one occasion an alarm of "Thief!" was given. "The house had been broken into, and all Dennis's clothes and money had been taken. Dennis's father sent for Mandarin. Mandarin come and examine great hole cut in the wall of house, where thief get in. He say, 'Thief live in house. Hole not made outside, but inside.' He go and look in uncle's room, and there find all my clothes! Father then take me away: he say I not live there any longer; and I live with grandmother—my mother's mother, not father's mother. But I then not l not like to go to School, because I got into bad ways when I live with uncle, and had no clothes to go in; so I run about, and nobody know I not go to School. It was very wicked of me, but I did not know any better: I did not know I was doing wrong."

At length his father married again; and he, in consequence, went home. His second mother was very kind to him; at least till she had a family of her own. She used to take the poor boy's part, and not allow his father to beat him; and, being much stronger than her husband, he was afraid of her, and dared not use her so cruelly as he had done his former wife, for "she was master of him."

But Dennis had now become too old to submit to the restraint of School, having been so long accustomed to ramble about instead. He used, therefore, to stay away, unknown to his mother.

When his father was at home from his fishing excursions, Dennis would frequently run away for days and nights together, that he might escape the chastisement of his cruel and passionate parent. At these times he used to live on what he could get by begging from his friends. During some of the Chinese festivals, it is customary among them to make presents to all their friends; and whatever Dennis got in this way, he used to lay by, that he might have something to fly to when his cruel father returned. He used, on occasions, to sleep in the open air; and the only shelter he had was the projecting front of the shops, which are made with a sort of verandah to protect the articles of sale from the sun. Once, after a severe beating, he ran away, and went to an uncle of his, who lived at Chusan, where he was kindly treated; but he was taken back again to his father, who had become uneasy about his long absence, and his uncle begged that he might not be beaten any more. On another occasion, after his father had been very severe with him, he was so afraid to go home, that, instead of doing so, he went to the fishing-vessel, where he found his brother, and there he passed the night. Early the next morning, when his father came, the brother interceded for the boy before he entered the boat, and obtained a promise that he would not hurt him. Having made this promise, he kept his word; but, as Dennis related it, "He look very cross, and he very angry with me for running away, but no more: he not beat me that time. At night, when we go home, as we go through the streets, when we get near home, he take me up wrong street: he want to do so, but I say, 'No, I not go: I know what you want; you want to take me up there and throw me into deep river from high wall, and I get drowned: I not go that way.' So I run away: I afraid of him; and I not go home till he gone to sea again."

When the war broke out, as soon as the English ships came to Shanghai, Dennis's friends all left the town, and went—he did not know where; for he never saw them again. He appears to have remained, and, along with another boy, to have wandered about, as he had often done before.

One night, when they were asleep under a theatre, which was occupied by some English soldiers, they were discovered, in consequence of the noise they made by snoring. One of the men gave them some straw to sleep on, and, in the morning, let them have some breakfast. As they were not unwilling to work, the soldiers used to employ them to light the fire, and clean the shoes, and go errands, &c., and purchase things for them. When the boys did what they were bid, they were kindly treated; but when they neglected to do so, the sergeant "gave them some stick." Dennis's young countryman soon got tired of being with the English, and returned to his friends: but Dennis's parents not having come back, he was glad to remain with his new acquaintances, who continued to employ him; and, on one occasion, he appears to have been of essential service to them. One day, when he was taking a walk, he observed one of his countrymen put something black out of a paper into the well, from which the English were accustomed to take the water for their tea. He immediately suspected it was poison. "Well," he said, "I say nothing—I take no notice: I go on my walk. I not go to English directly, for fear man see, and then run away, but I go back a long way round. I say nothing when I get to soldiers, but wait. Presently one of them get bucket to go for water. I say 'No, not go there.' I shake my head to make him know water bad. I take soldiers to shop of Chinaman that put poison into the well. We tell him to come, but he say, No, he won't. But then we make him come: and when we get to well, one of soldiers fill bucket, and tell him, 'Drink;' but he say, No, he would not. They say they shoot him if he do not drink; but still he say, 'No.' So they were sure that I had told them true, and they take Chinaman to Mandarin to be punished, and destroy his shop. I still stay with English; and when they come away they give me my choice—either they give me money, or take me with them to England, because I tell them about the well. I say, 'I go to England: I not have money. If I stay in China, Mandarin beat me when English gone, perhaps kill me, because I help English, and tell about the well.' So I go with soldiers, and they take me on board the 'Blonde;' and then Captain Foster bring me all over the sea to England, where God has given me kind friends, who tell me about Jesus Christ."

The poor boy, on his arrival in England in 1843, having been brought under the notice of Earl Fitzwilliam, was placed by that nobleman at Mr. Beardshall's academy at Ashcroft. The Christian instruction received by him there was blessed to his conversion. When he reached England he was as others of his countrymen, "without God;" but his dark mind gradually opened to the light of God's mercy in Christ, and, at his own request, he was baptized on Sunday, October 15, 1848. No doubt rested on the minds of those who knew him that he was taught of God, and, having found peace in believing, he earnestly desired to go back to China and instruct his countrymen. Some of his schoolfellows once asked him why he wished to be a Missionary. In the most animated manner he answered in words like the following—"Have you any brothers or sisters?" "Yes," was the reply. "Well, then, if any one told you of a great treasure, more than enough for the wants of all your family, and that it might be yours, would you not considered yourselves rogues if you did not let your brothers share with you? Now I have been told of such a treasure in Jesus Christ; and should I not be doing wrong if I did not go and tell my brothers and sisters—the poor ignorant people of China—all I know about Him?"

It pleased God, however, to order it otherwise, and to remove him from this world to join the spirits of just men made perfect, who, in the presence of their Lord and Savior, await the promised resurrection. Severe disease attacked him, of a lingering character, but which admitted not the prospect of recovery; painful, yet patiently borne, and used by his Lord and Savior as the refiner's fire to prepare him for his transfer to heaven. "I suffer," he said, "great pain: no one know what I suffer. But what is it? I deserve it all. It not one bit too much: it nothing like what Jesus suffer for me; so I'll bear it patiently." To a friend, who came to see him about this time, he said, "Oh, my sufferings so great, my pain so bad! What do you think it is keep me alive now?" Putting his hand on his Bible, he added, "it is this; this keep me alive. You know Jesus says, 'Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God;' and it is that keep me alive now: nothing else could."

He who brought Dennis to this country, and made him here a subject of grace, has deigned in his history to convey to us a lesson. What the Gospel did for him, it can accomplish for his countrymen. Dead as they are to every thing of a spiritual nature, "God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham." What Dennis wished to do, let us, then, do instead of him; and by diligent effort and self-denial provide that the Gospel be extensively preached to the Chinese, for, as we may each say in the words of this now happy youth—"How shall I meet the heathen in the day of judgment, when they cry with a loud voice against me, that I lived on earth when they did, and that I got to know the way to heaven, and yet I went not [nor sent] to tell them!"

* June and July 1850. [back]

Digital Publication Details

Title: “The Outcast from China Brought Safely Home”

Creator(s): Anonymous; John Dennis Blonde

Publication date: (1851) 2022

Digital publishers: One More Voice, COVE

Critical encoding: Kenneth C. Crowell, Cassie Fletcher, Jocelyn Spoor, Adrian S. Wisnicki

One More Voice identifier: liv_026011

Cite (Chicago Author-Date): Anonymous, and John Dennis Blonde. (1851) 2022. “The Outcast from China Brought Safely Home.” Edited by Kenneth C. Crowell, Cassie Fletcher, and Jocelyn Spoor. In “BIPOC Voices,” One More Voice, solidarity edition; Collaborative Organization for Virtual Education (COVE). https://onemorevoice.org/html/bipoc-voices/digital-editions-amd/liv_026011_HTML.html.

Rights: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Accessibility: One More Voice digital facsimiles approximate the textual, structural, and material features of original documents. However, because such features may reduce accessibility, each facsimile allows users to toggle such features on and off as needed.