Overview

This essay discusses the 1902 Addis Ababa Treaties. These historical documents have been critically curated and published by the Ardhi Initiative and are now republished by One More Voice. The 1902 Treaties offer a significant window into the Scramble for Africa in the period after the 1884 Berlin Conference. They serve as an example of how various African political entities maneuvered in the face of European imperialism.

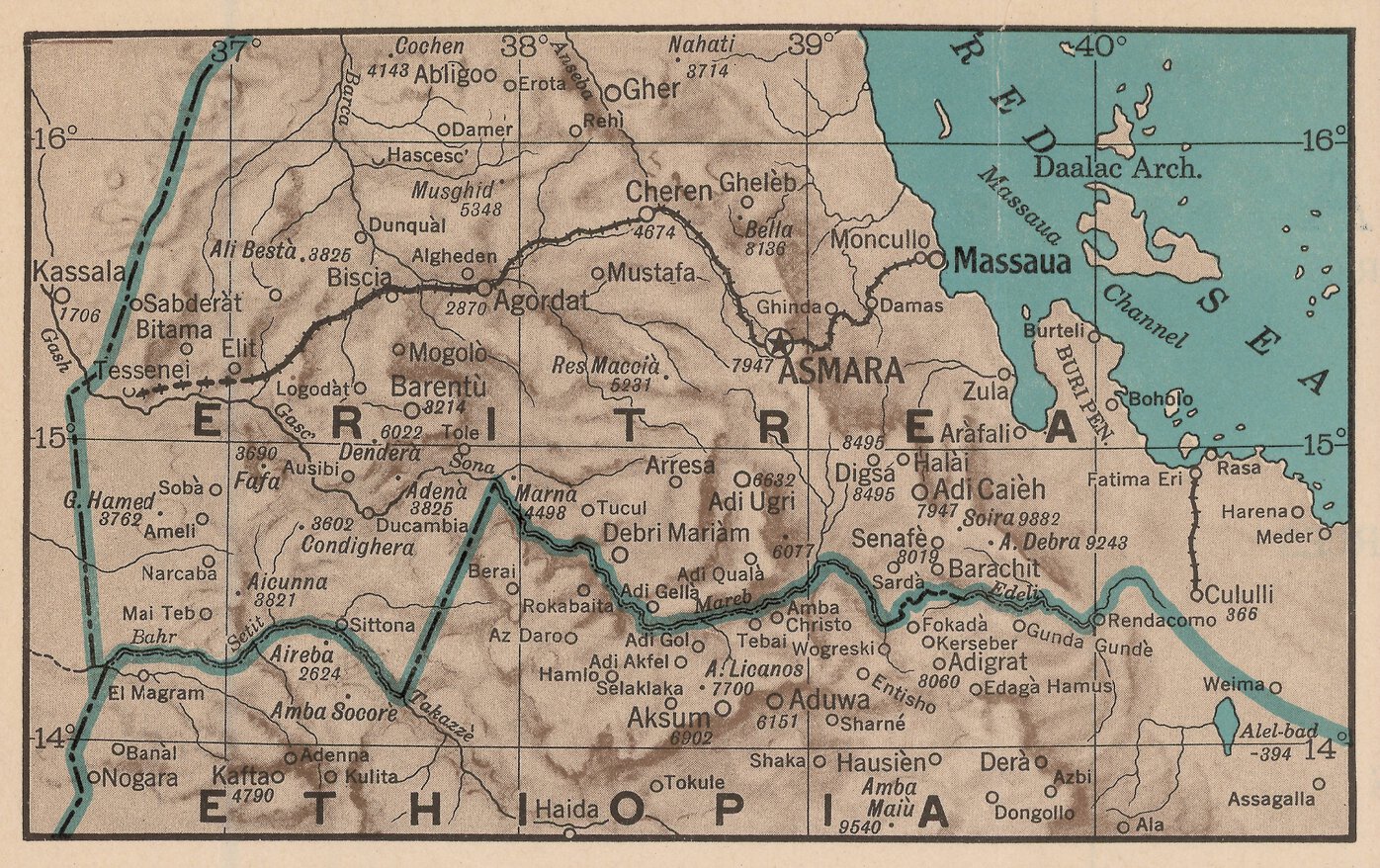

Today, the Treaties are still vital historical documents to re-examine because they sparked a series of border skirmishes that Eritrea and Ethiopia transcended just recently (2018). This essay argues that these treaty documents have acquired a sort of “zombie” characteristic. The political challenges attendant to these treaties have never been quite laid to rest; instead, the challenges continue to mutate or shift into the present day to further aggravate sections of the Eritrean and Ethiopian populace.

Ethiopia-Eritrea Relations, 1900-2020

In 2019, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali received the Nobel Peace Prize for “his efforts to achieve peace and international cooperation, and in particular for his decisive initiative to resolve the border conflict with neighboring Eritrea” (Nobel Prize 2019). Abiy’s efforts towards peace were widely acclaimed, given the Ethiopia-Eritrea state of conflict since 1998. The resulting bilateral agreement ended a costly two decades of direct and proxy wars.

The political circumstances for the Eritrea-Ethiopia geo-political struggle had been determined more than a century earlier when Emperor Menelik II of Abyssinia signed treaties with Great Britain and Italy in May 1902. At the time of their signing, these treaty documents demonstrated that the Ethiopian monarchy, alone across the African continent, had succeeded in forcing the European colonial powers to reckon with its sovereignty. This can be directly attributed to Ethiopia’s military victory over Italian forces at the March 1896 Battle of Adwa.

In leading Ethiopian soldiers at Adwa, Menelik demonstrated his ability to adapt European military technology towards his own goals. In the years after signing the treaty, Ethiopia’s monarch embarked on technological modernization (for another example of Menelik's work in adapting European technology, see his phonograph message to Queen Victoria [circa 1910]), survived in exile to escape Fascist Italy’s occupation, and was eventually overthrown by military officials in the early 1970s.

Eritrea, which had been under Italian rule since the late nineteenth century, was taken over by the British at the onset of WWII, and eventually federated into Ethiopia in the 1950s. From the mid-1960s onwards, Eritrean independence was at the forefront of all relations between the two communities. The conflict, sometimes violent, was finally resolved with Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia in the early-1990s. But major hostilities between the two nations in 1998-2000 demonstrated that territorial sovereignty was still unresolved. It is the remnants of this war that Abiy is feted for having quelled, finally.

The Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission

The Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) was convened in 2000 and delivered a decision in 2002. In conjunction with the United Nations and the African Union, the Boundary Commission took steps between November 2002 to 2003 to demarcate the Ethiopian-Eritrean border. However, due to unresolved disputes, the demarcation process was discontinued and subsequent attempts to restart the process in 2006 and again in 2008 proved unsuccessful.

In 2008, the Eritrean government approached the International Criminal Court at The Hague to help adjudicate what had morphed into a border conflict. The Boundary Commission reviewed each sides’ claims, as well as land treaties signed by Menelik with Great Britain and Italy in 1902 (this set is republished by One More Voice), 1908, and 1911. In other words, the treaties signed by Menelik with European powers in the early twentieth century continued to have considerable significance in the early twenty-first century, a hundred years after they were signed under very different historical circumstances.

The 1902 Addis Ababa Treaties and the Ardhi Initiative

Present-day African land disputes are closely tied to global European imperialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Between 1885 and 1950, over 80% of African lands belonged to – and were governed by – Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. The era of African self-governance in the 1950s and 1960s unsuccessfully sought to address this resource inequity. As a result, resolving the challenges that farmers, pastoralists, home-owners, ranchers, industrialists, etc. face in acquiring land remains crucial for Africa’s ability to feed its people and generate employment in the present day.

The 1902 Treaties, therefore, can also be understood within this wider historical context and, indeed, that has been the approach taken by the Ardhi Initiative, a digital humanities project led by the present author that focuses on on investigating the 1850-1960 history of African land acquisitions with the goal of re-discovering home-grown solutions to continental challenges that cross multiple knowledge areas including human geography, agriculture, political economy, sociology, and anthropology. The long-term goal of this project is to identify connections and patterns that emerge across the African continent over a 100-year period and to ascertain varied continent-wide approaches that sustainably resolve land inequality.

Overall, the Ardhi Initiative aims to achieve the following objectives:

- digitize and encode sovereignty treaties between European nations and African political entities;

- curate encoded documents online for use by other scholars;

- perform Natural Language Processing on encoded data;

- determine patterns of rhetoric regarding land use; and

- produce data visualizations and publicly disseminate research findings.

The Ardhi Initiative emerged from research for the present author’s monograph, Writing on the Soil: Land & Landscape in Literature from Eastern & Southern Africa. This monograph examines the aesthetic and metaphorical uses of land and landscape in select Eastern and Southern African writing. By exploring this rich history, including the ways in which language influences depictions of human and/or non-human animals in different geographies since the mid-Sixties, the monograph engages with colonial depictions of African land(scapes) in treaties and other imperial documents.

Conclusion: The Tigray Impediment

A postscript to the one-hundred-year-history of regional relations in the Horn of Africa involving Ethiopia and Eritrea was added quite recently. In November 2020, conflict broke out between Ethiopian government forces and armed groups in Ethiopia’s Tigray province. This rivalry was set off by changing political coalitions in previous years and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy’s supposed sidelining of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front within the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front coalition. However, the contours of the conflict also indicate that Eritrea has now joined what was essentially an Ethiopian domestic dispute.

These developments, in turn, go back to the original terms of the 1902 Treaties and the 1908 and 1911 treaties that followed. The intertwined nature of ongoing Eritrean and Ethiopian relations reveals the highly problematic conceptualization of the original colonial treaties that split the region into two independent nation states. For instance, Tigrinya speakers straddle both sides of the boundary. Aside from linguistic affinity, there also exists cultural proximity, including a shared Christian religion.

This complexity is best exemplified in the 1902 Treaties by repeated references to the waterways shared by Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Sudan, including the Blue Nile, Baro, Pibor, and Akobo Rivers. Given that rivers change their flow paths with time – sometimes significantly shifting topographies – rigid legalistic language of the treaties proves highly problematic when put in the context of such natural geographic patterns.

For instance, Article III of the 1902 Treaties (in which Emperor Menelik II pledges not to allow any infrastructural construction along the Blue Nile, Lake Tsana, or the Sobat), has in the present-day spawned diplomatic conflict regarding Ethiopia’s just-completed Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Visible from space, the GERD is a massive hydro-electric project that threatens downstream communities in Egypt and Sudan with drought, especially given the drying up of the Nile River. 120 years later, Menelik’s pledge to foreign colonial powers complicates a genuine conversation amongst the Nile River countries on how to share water resources.

Ethiopia’s contemporary geopolitical and ecological policies are thus massively determined by colonial treaties inked in the early twentieth century. It is absolutely crucial that these colonial documents be re-examined and publicly discussed. The efforts of the Ardhi Initiative to collect, digitize, and publish such treaties and the work, in this case, of One More Voice to recontextualize one such set of treaties among the site’s other recovered texts both, consequently, contribute to the larger project of such historical re-evaluation.

Further reading

Cotula, Lorenzo. 2013. The Great African Land Grab?: Agricultural Investments & the Global Food System. New York: Zed Books.

Graham, James. 2009. Land & Nationalism in Fictions from Southern Africa. New York: Routledge.

Hague, The. 2014. “Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission.” The Hague Justice Portal, 2014.

Kenyatta, Jomo. 1962. Facing Mt. Kenya. New York: Vintage.

Levine, Donald. 2009. “The Battle of Adwa as a ‘Historic’ Event.” Ethiopian Review, March.

Maughan-Brown, David. 1985. Land, Freedom & Fiction: History & Ideology in Kenya. London: Zed Books.

Menelik II. Early 1900s. “The Voice of Ethiopian King Emperor Menelik II [Message to Queen Victoria].” Sound Recording. Addis Ababa. YouTube.

NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Space Systems, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team. 2020. “Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.” Jet Propulsion Laboratory: California Institute of Technology, November 10, 2020.