Introduction

One More Voice publishes two letters by Frederick Douglass (1818-95), the foremost abolitionist and advocate for African Americans in the nineteenth century. He wrote the first on 9 May 1846 to John Scoble, co-founder of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society; the second on 9 July 1888 to Catherine Impey, an English activist and editor who denounced the persecution of Black Americans in the Post-Reconstruction period. The letters exemplify the support Douglass received from British allies throughout his public life. They also engage with the two great causes that defined his long career: the abolition of slavery and the struggle for the dignity and equality of Black Americans.

Douglass wrote to John Scoble during a spirited speaking tour of Ireland, Scotland, England, and Wales in 1845-47, a pivotal experience that transformed him from a protégé of white abolitionists in the United States into an independent political force. Scoble had invited Douglass to the anniversary of the BFASS in London on 18 May 1846. Replying from Edinburgh, Douglass thanks Scoble for the invitation but sends his regrets that he will not reach the capital in time, stressing the importance of the matter that detained him in Scotland. In fact, Douglass did manage to reach London by the 18th to attend a full week of meetings (Thompson 1846), culminating with one of the most powerful speeches of his career: the Finsbury Chapel Speech, which he delivered under the auspices of Scoble’s organization on 22 May 1846.

Douglass addressed the letter to his friend Catherine Impey more than four decades later in 1888, from Cedar Hill, his home in Washington, DC. The letter formed part of an ongoing correspondence between the two about the injustice and brutality of white supremacy in the United States and what could be done to end it. Impey was founding a new movement in Britain to take up the cause of racial justice where the old anti-slavery societies (including Scoble’s) had left it (Bressey 2013, 27). In the letter, Douglass expresses hope, faith, and gratitude to Impey for her efforts. Although he declines her invitation to return to England, he commits his prestige to her venture and encloses a donation of $5 in support of her new journal, Anti-Caste.

This avuncular response reflects Douglass’s change in stature since writing to Scoble in 1846. The young, sensational hero who had escaped slavery and traveled to Britain to campaign for abolition relished the platform and endorsement Scoble offered him. However, by the time Douglass corresponded with Impey in 1888, he had become a revered elder statesman. It was now for him to bestow credibility on Impey as an up-and-coming activist, a new British ally willing to attack the violence and oppression faced by Black Americans.

Biographical Background

Boyhood and Literacy

Douglass was born in rural Maryland in 1818 to an enslaved woman whom he saw only a few times before her death in 1825 and a white man, likely his master. One of his earliest memories was of his mother, who worked at a farm twelve miles away, coming to visit him at night in his grandmother’s cabin. But he saw her so infrequently that for him there was no emotional bond. He would later cite this in his autobiographies as one of many ways that slavery destroyed families (Blight 2018, 9; Douglass 1984, 18–19).

At the age of seven, Douglass was sent to serve in the house of Hugh and Sophia Auld in Baltimore, where his mistress naïvely began to teach him to read alongside her own son. It was axiomatic among slaveholders that their “human property” (Douglass 2003, 134, 159) must be kept illiterate and uninformed as well as brutalized, terrified, and isolated in order to prevent them from banding together for insurrection. In this way, enslaved people were prevented from reading about the abolitionist movement and could not study the Bible, lest they perceive that their bondage was not divinely mandated. Hugh Auld’s brother Thomas, Douglass’s legal owner, declared himself reborn at a Methodist camp meeting that Douglass (now a teenager) also attended; his master was his “brother in the church” (Douglass 2003, 169). But when “Master Thomas” learned of a new Sunday school in which Douglass taught fellow slaves to read, he arrived with other members of the church to break it up with “sticks and other missiles” (Douglass 2003, 112–13; 142–47; Blight 2018, 34–35).

These early experiences of enslavement, faith, and injustice informed Douglass’s rhetoric as an abolitionist. Slavery disrupted the most sacred bonds of affection. It was enforced by ignorance and violence, and it occasioned religious hypocrisies that, Douglass believed, should outrage Christians everywhere. The religious argument features prominently in the 1846 letter to Scoble and in the ensuing Finsbury Chapel Speech.

Early Career in Abolitionism and Fame

Douglass escaped his enslavement in 1838 and reached New York, where he reunited with his fiancé, Anna Murray, a free Black woman he had met in Baltimore. They were married there by J. W. C. Pennington, a fellow escapee from Maryland, at the home of David Ruggles, the leading abolitionist in the city (Blight 2018, 84). The newlyweds made their way to New Bedford, Massachusetts, a center of the whaling industry where the demand for labor made Black workers relatively welcome. Douglass soon found work as a common laborer and supported his family with jobs on and near the wharves for three years (Douglass 2003, 257).

During this period he began reading William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator (Douglass 2003, 260), and in August 1841 he was inspired to attend an anti-slavery convention on the island of Nantucket. He was urged to speak at the convention and did so, haltingly at first, but soon astounding his auditors with his diction, intellect, and dignity (Blight 2018, 99-100). As a self-educated former slave, Douglass was a unique and impressive figure. He was soon in demand as an orator. Speaking often in churches – the abolitionists were mostly churchmen and women – he castigated his old masters and lampooned the false pieties of slaveholders to raise outrage among Northerners of the same denominations (Blight 2018, 102-115).

In 1845, Douglass’s fame accelerated with the publication of his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself, which he wrote in part to prove to skeptics that he truly was born a slave. The book was a sensation, and its wide-spread fame put him in peril of being captured and returned to the South. This spurred him to go abroad to continue his advocacy beyond the reach of slave catchers. Intending to sell more books and earn money for his wife and children, Douglass embarked on a twenty-one-month lecture tour of Ireland and Great Britain in August 1845 (Douglass 2003, 243, 255, 263–64, 267–69; Blight 2018, 138–40).

In Britain, Douglass impressed his audiences with his manners, eloquence, and above all intelligence, all of which defied common expectations of a formerly enslaved person. As a speaker, he modulated his baritone delivery, cannily deploying pathos, sarcastic comedy, and indignation. He entertained his listeners with stories of his former life, including cruelties he suffered and witnessed, and flattered them by remarking on the liberty he enjoyed in their monarchical nation, as opposed to the demeaning treatment that even free Blacks endured in the supposedly democratic United States. The acclaim Douglass received abroad raised his profile at home, where the abolitionist press publicized his activities to the consternation of the slaveholders (Blight 2018, 102, 104, 157-58; Douglass 1950, 209).

These experiences and the relationships he formed with British allies like John Scoble primed him for the trajectory his career would take in America. The 9 May 1846 letter to Scoble is a record of his emerging independence. Douglass had come to Britain as the emissary of the white abolitionist movement led by Garrison, but Douglass’s own talent and persuasiveness made him a celebrated figure, and he soon found friends and contacts of his own. These included the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS), which Garrison considered a rival organization (Blight 2018, 169).

Among other supporters Douglass met in Britain, BFASS members were eager to raise money for him, taking up a collection to bring his wife and children to England (Douglass 2003, 315). This did not occur, but British donors succeeded in purchasing his freedom from the Aulds so he could re-enter the United States without fear of capture; others contributed money for the launch of his own abolitionist newspaper, the North Star (Blight 2018, 171, 190). With this backing, Douglass returned to America in 1847 very much his own man. He was ready and equipped to become a political force to be reckoned with, both in the immediate campaign for emancipation and in the long fight against white supremacy that lay ahead.

Subsequent Honors, Remarriage, and Later Activities

Douglass settled his family in Rochester, New York, and he traveled and lectured widely while also writing for and editing The North Star (later known as Frederick Douglass’ Paper). The paper was co-managed and co-edited by Julia Griffiths, an English abolitionist he met in London who assisted him in Rochester from 1849-55 (Blight 2018, 204, 221).

Douglass went on to publish a second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), with an expanded and somewhat more melodramatic account of his years in slavery – partly in response to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s depictions of slavery in her extremely popular novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). After the Dred Scott decision in 1857 reinforced the legality of slave ownership, Douglass warned of violence to come and supported the radical abolitionist John Brown, although he stopped short of joining Brown’s suicidal raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Douglass called on Black young men to join the fight against the Confederacy. He was subsequently received at the White House by Abraham Lincoln, with whom he discussed the conditions of Black troops in the Union Army (Blight 2018, 171, 190, 196, 277, 279, 293ff, 342, 408–10).

After the war and Emancipation, Douglass edited the New National Era, a Washington newspaper from 1870-72, served briefly as president of the Freedman’s Savings Bank (1873), and continued to tour extensively as a public speaker. He was named Marshal of the District of Columbia in 1877 and Recorder of Deeds in 1881, posts that ensured him of a steady income; later he would serve as US envoy to Haiti (1889-91). In the centennial year of 1876 he was invited to give the keystone address at the unveiling of a monument to Lincoln, with dignitaries including President Ulysses S. Grant in attendance. Balancing praise with criticism, he stated frankly that Lincoln was “the white man’s President” who would have allowed slavery to continue, though he abhorred it, if it meant keeping the Union intact. It is impossible to imagine any other Black American making such a speech. On other occasions, he criticized the memorial itself, which featured a near naked Black man, his chains broken, kneeling at Lincoln’s feet (Blight 2006; Douglass 2018, 344; Sandage & White, 2020).

Douglass was so widely esteemed that he dared to unite with a white woman in an open interracial marriage after the death of Anna Douglass in 1882. Helen Pitts, nearly twenty years his junior, was a graduate of Mount Holyoke College and a suffragist who had worked for him in the deeds office (Blight 2018, 649–54). Douglass had long cultivated relationships with female intellectuals and activists. He was an early proponent of women’s suffrage, which he famously endorsed at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, the seminal event of the feminist movement in the United States. He maintained these views, supporting rights for women in an era when it was commonly considered ridiculous to do so (Blight 2018, 171, 196).

Given his belief in gender equity, it is not surprising that Douglass was receptive to the ideas of Catherine Impey, an unknown Quaker Englishwoman who first reached out to him in 1883. Douglass corresponded with and exchanged visits with Impey as she launched an ambitious anti-racist movement (Impey’s term was “anti-caste” and this later became the title of the journal she published, Anti-Caste) in concert with a Scotswoman, Isabella Fyvie Mayo. This extended Douglass’s long history of alliances with British activists that began with his first visit to the British Isles in the 1840s.

Final Years

The need for anti-racist advocacies such as Impey’s became ever more clear to Douglass in his final years, as he was dismayed by a resurgence of brutal repression in the South and hardening color lines in the North. After the Civil War, freedmen in the former slave states had gained constitutional rights and representation in Congress, but with the withdrawal of occupying Union troops these advances were wiped out. Voting and property rights were sharply curtailed, as Black Americans were terrorized and murdered with impunity by white lynch mobs (Anderson 2006). In the North, things were somewhat better, but segregation and demeaning prejudice prevailed.

The frustrations of prejudice culminated for Douglass with the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, which featured denigrating depictions of non-white cultures. Douglass was closely involved in the Haitian Pavilion and hoped in vain that the wildly popular fair could be used to draw attention to Black progress. However, “African American proposals and exhibits were rejected by the fair’s organizing committees” and non-white visitors were excluded, except for a segregated “Colored People’s Day” (Blight 2018, 734). Douglass spoke out against these affronts, facing down white hecklers and calls from younger Black leaders to boycott the Exposition altogether. He raised funds to print 10,000 copies of The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition (1893), a protest pamphlet by Ida B. Wells, a Black American journalist, anti-lynching advocate, and suffragist. Douglass and others handed out the pamphlet at the fair (Blight 2018, 733-34, 737-38).

In the same year, Douglass urged Wells to accept an invitation to Britain for a speaking tour co-sponsored by Catherine Impey. The tour echoed his own in the 1840s, bringing his career full circle in ways that were both triumphant and heartbreaking. He began under the tutelage of a great abolitionist leader, William Lloyd Garrison; now he was the elder statesman, encouraging a new messenger to carry the cause of racial justice across the Atlantic. The struggle for equality had suffered bitter setbacks, but he could take heart in the rise of new leaders, including Wells and Impey – female activists who endorsed both racial and gender equity, as he had done nearly fifty years earlier at Seneca Falls. Douglass, aged 77, collapsed at Cedar Hill and died of an apparent heart attack on 20 February 1895 (Blight 2018, 752).

The Letters Published by One More Voice

The letters to John Scoble and Catherine Impey published by One More Voice bookend Douglass’s extraordinary public career. The letter to Scoble comes from the period when Douglass rose to international prominence and became a leading abolitionist. The letter to Impey grows directly out of the concerns and frustrations of racism, the problem that occupied Douglass’s later life and set the course for the Civil Rights movement of the next century.

The Letter to John Scoble, 9 May 1846 and the Finsbury Chapel Speech

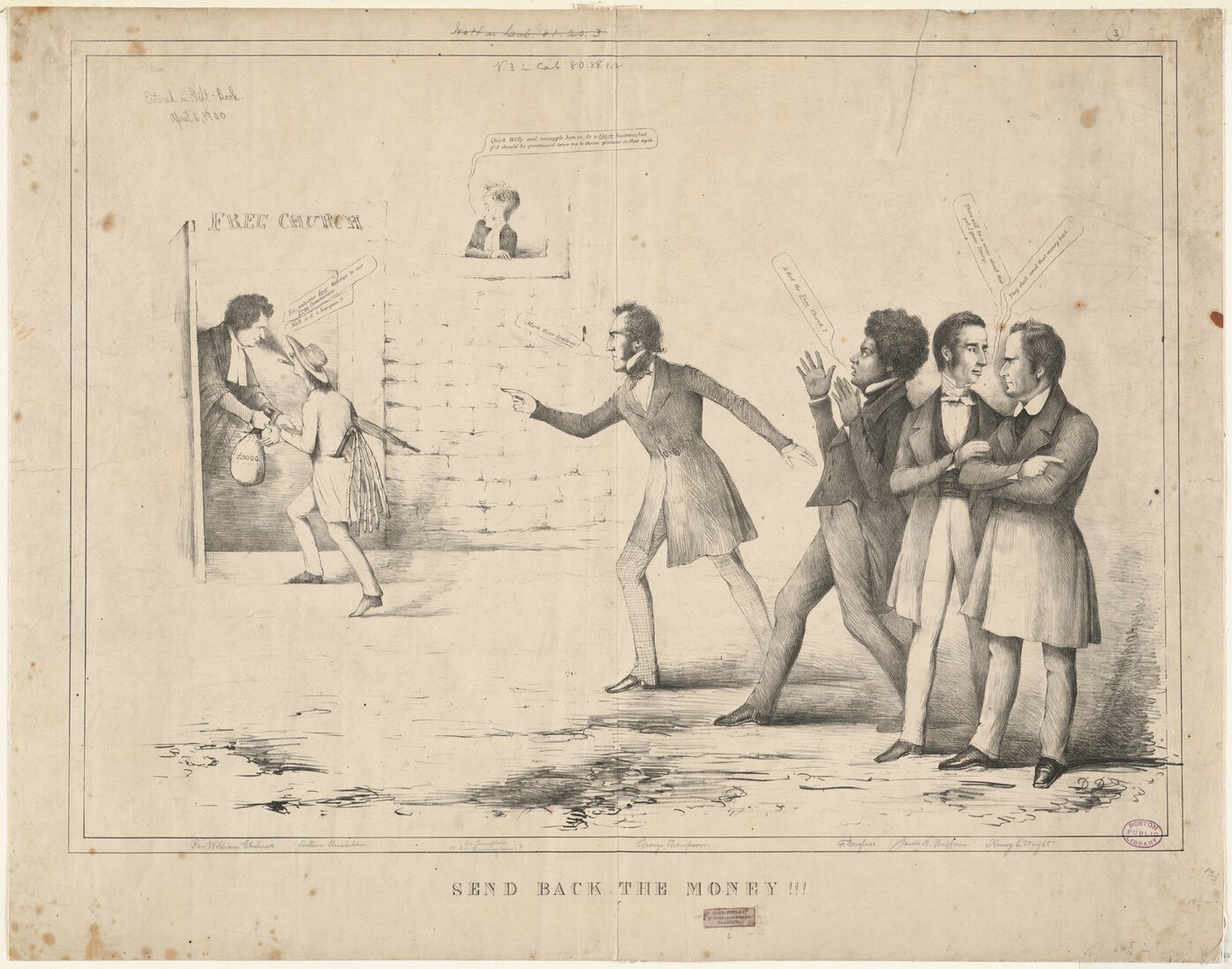

Douglass’s letter to John Scoble belongs to the pivotal 1845-47 period. Scoble was a British-Canadian Congregational minister and an activist in the international anti-slavery movement (Jones 1976). In the letter, Douglass responds to an invitation to attend the anniversary of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in London on 18 May 1846. Writing from Edinburgh, Douglass informs Scoble that he would not reach London in time because he expects to be detained by the ongoing “Send Back the Money'' campaign against the Free Church of Scotland, which had solicited contributions from American slavers (Blight 2018, 156-59; Douglass 1846, pp. 0001-0004). He goes on to explain his determination “that British Christians of all denominations should declare non fellowship to slave holders” and adds that slavery in the United States exists only “because it is not so disreputable [abroad] as it ought to be” (Douglass 1846, 0002-0003).

Despite what he writes in the letter, however, Douglass did reach London in time for the meeting of Scoble’s Anti-Slavery Society, which arranged for him to deliver a major speech a few days later at Finsbury Chapel, a large venue in South London. On 22 May 1846, Scoble was among the dignitaries on the platform as Douglass addressed an audience estimated at between 2,500 and 3,000 for nearly three hours (Blight 2018, 175; British and Foreign 1846, 95–96).

At the outset of the speech, Douglass explained that news of his activities reached the United States and that he derived a fugitive slave’s satisfaction from taunting the planters, especially because the wealthiest slaveholders styled themselves after English aristocracy and sent their sons to learn refinement in the parent country. Indeed, Douglass had clashed with some of these individuals during his crossing and meant to deny them the legitimacy they sought (Douglass 2003, 270, 303).

In the speech, Douglass then went on to detail some of the cruelties endured by enslaved people in the American South at the hands of purportedly enlightened masters. The descriptions of physical atrocities set up his attack on Southern religion, the paternalistic ideology that, as he explained, cast slavery as an expression of divine order. The claim that “the bible endorsed slavery,” he added, was used to convince slaves of the rightness of their bondage and assure white masters that they were the generous benefactors of inferior beings (Selby 2002, 326). For Douglass, this was sacrilegious fraud.

In the climax of the speech, Douglass thundered home his point in the manner of a skilled preacher, moving his audience to emit “loud cheers,” and cries of “shame!” (British and Foreign 1846, 96). He urged his listeners to render the planters “disreputable,” as he had written to Scoble (Douglass 1846, 0003), by severing all legitimizing ties. The audience responded with enthusiasm, “heartily” raising the Scottish cry, “Send back the money!” (British and Foreign 1846, 96).

The Finsbury Chapel Speech thus brought into focus the strategy that Douglass had referenced in his earlier letter to Scoble: raising moral outrage at the slavers’ misuse of Christianity as an instrument of repression and calling for ecclesiastical repudiation to undermine the legitimacy of the slave economy.

The Letter to Catherine Impey, 9 July 1888

The letter to Catherine Impey, written more than forty years later, belongs to a later stage and a different mood in Douglass’s long career. In the letter, he signifies his appreciation of Impey by adopting her terminology of universal “human Brotherhood.” While he declines her invitation to revisit Britain, he encloses $5 to support her new journal, Anti-Caste (Douglass 1888, 0001).

A Quaker activist from Somerset, England, Catherine Impey (1847-1923) visited the United States in 1878 and quickly forged friendships with Black Americans. She soon realized that racism was woven into the fabric of daily life in America (Bressey 2013, 9, 36). Determined to fight the evils of prejudice and segregation, Impey contacted Douglass in 1883 to propose a new transatlantic movement to succeed and surpass the goals of anti-slavery organizations such as the BFASS. She launched Anti-Caste in 1888 to draw attention to the injustices of white supremacy in the United States and the colonies of the British empire. The publication proudly listed Douglass as one of its lifetime subscribers (Bressey 2013, 17, 23, 27, 57).

Impey’s use of the term “anti-caste” did not refer specifically to the caste system in India but to prejudice of any kind based on ethnicity, skin tone, gender, or social class. She avoided using the term “race,” which was associated with the spurious theory of fundamental biological differences between people of different complexions (Bressey 2013, 1, 17-18). She argued that caste segregation in the United States created “fear” of the Black other, “groundless [white] panic” that led to violent persecutions of African Americans (Impey 1895, 29, emphasis in original).

Overall, the letter serves as a link in a chain of correspondence between Douglass and Impey that culminated in 1893, when Douglass encouraged Ida B. Wells to go to Britain in his stead. If the letter to Scoble is an artifact of Douglass’s arrival on the international scene, the letter to Impey signifies his withdrawal, the start of his ceding his place to a new generation.

Postscript: Douglass, Impey, and Wells

Impey’s contributions to social justice advocacy would be forgotten if not for Ida B. Wells (1862-1931), who describes their relationship in her unfinished autobiography. When the two met in Philadelphia in 1892, Wells was a frustrated exile and an activist of rare courage who had been forced to flee her co-editorship of a Memphis newspaper after protesting the inequities of school segregation and the horrific rise of lynching (Bressey 2013, 9, 76-78).

When it became apparent that the aging Douglass would not travel to Britain, Impey and her collaborator, Isabella Fyvie Mayo, invited Wells to undertake a lecture tour to speak about lynching, in particular the fact that Black Americans, usually men, were murdered by lawless white mobs, typically on trumped-up charges of raping white women. Impey published a photograph of a hanged victim on the cover of the January 1893 issue of Anti-Caste. It was a souvenir image with white Southerners posing beneath the dead body. Reprinted and recaptioned under the banner of Anti-Caste, it became a visceral condemnation of depravity and injustice (Bressey 2013, 112-15).

The invitation from Impey and Mayo was forwarded to Wells at Cedar Hill, where she was staying with Douglass and his wife Helen Pitts. Wells handed it to Douglass to read. To reassure the young woman (who knew her correspondents would have preferred to have him), Douglass said: “You go my child, you are the one to go, for you have the story to tell.” Wells was elated at the opportunity: "It seemed like an open door in a stone wall" (Wells-Barnett 1970, 85-86).

In two speaking tours, in 1893 and 1894, Wells sparked acclaim and fascination in Britain as Douglass had before her. She spoke before audiences large and small about the atrocities at home, including brutal enforcement of segregation, intimidation of Black voters, and laws prohibiting interracial marriage. Backed by Douglass and Impey, the campaign amplified her voice as a civil-rights activist and organizer (Bressey 2014, 140-43).

Wells was not Douglass’s only successor as a Black American advocate, but she was a worthy one, whose achievements would include a central role in founding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (Willis 2001). In the 1840s, Douglass received a warm welcome and welcome support from British abolitionists, including John Scoble. Nearly fifty years later, Wells too found support in Britain, this time from Catherine Impey and her groundbreaking anti-caste movement.

Works Cited

Anderson, Eric. 2006. “Black Politics.” In Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass. Oxford University Press.

Blight, David W. 2006. “Douglass, Frederick.” In Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass, edited by Paul Finkelman. Oxford University Press.

Blight, David W. 2018. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Bressey, Caroline. 2013. Empire, Race and the Politics of Anti-Caste. First ed. Bloomsbury Academic.

Bressey, Caroline. 2014. “Geographies of Early Anti-Racist Protest in Britain: Ida B. Wells’ 1893 Anti-Lynching Tour in Scotland.” In Africa in Scotland, Scotland in Africa: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Hybridities, edited by Andrew Lawrence and Afe Adogame, 14:137–49. Africa-Europe Group for Interdisciplinary Studies. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. 1846. “American Slavery.” Anti-Slavery Reporter under the Sanction of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society 1 (6): 95–96.

Douglass, Frederick. 1846. “Letter to John Scoble. 9 May 1846.” Manuscript. MSS. Brit. Emp. s. 18, C16/75. Bodleian Library, Oxford. Also published by One More Voice.

Douglass, Frederick. 1888. “Letter to Catherine Impey. 9 July 1888.” Manuscript. MSS. Brit. Emp. s. 20, E5/7. Bodleian Library, Oxford. Also published by One More Voice.

Douglass, Frederick. 1950. “Farewell Speech to the British People, at London Tavern, London, England, March 30, 1847.” In The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, edited by Philip Sheldon Foner, 1:206–33. New York: International Publishers.

Douglass, Frederick. 1984. The Narrative and Selected Writings. New York: Modern Library.

Douglass, Frederick. 2003. My Bondage and My Freedom. Edited by John David Smith. New York: Penguin Classics.

Douglass, Frederick. 2018. “The Freedmen’s Monument to Abraham Lincoln.” In The Speeches of Frederick Douglass: A Critical Edition, edited by John R. McKivigan, Julie Husband, and Heather L. Kaufman. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Impey, Catherine. 1895. “Fear: The Explanation.” Bond of Brotherhood, no. 2, New Series (February): 29.

Jones, Elwood H. 1976. “Scoble, John.” In Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IX (1861-1870).

Masur, Kate. 2006. “New National Era.” In Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass. Oxford University Press.

Pettinger, Alasdair. 2018. Frederick Douglass and Scotland, 1846: Living an Antislavery Life. First ed. Edinburgh University Press.

Sandage, Scott, and Jonathan W. White. 2020. “What Frederick Douglass Had to Say About Monuments.” Smithsonian Magazine, June 20, 2020.

Selby, Gary S. 2002. “Mocking the Sacred: Frederick Douglass’s ‘Slaveholder’s Sermon’ and the Antebellum Debate over Religion and Slavery.” The Quarterly Journal of Speech 88 (3): 326–41.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. 1852. Uncle Tom’s Cabin or, Life among the Lowly. Boston: John P. Jewett & Company; Cleveland, Jewett, Proctor & Worthington.

Thompson, George. 1846. “Letter to Henry Clarke Wright.” Manuscript. Digital Commonwealth: Massachusetts Collections Online (Boston Public Library. Rare Books Department).

Wells-Barnett, Ida. 1970. Crusade for Justice; the Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Edited by Alfreda M. Duster. Negro American Biographies and Autobiographies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Willis, Miriam DeCosta. 2002. “Wells-Barnett, Ida B.” In The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature. Oxford University Press.