Overview

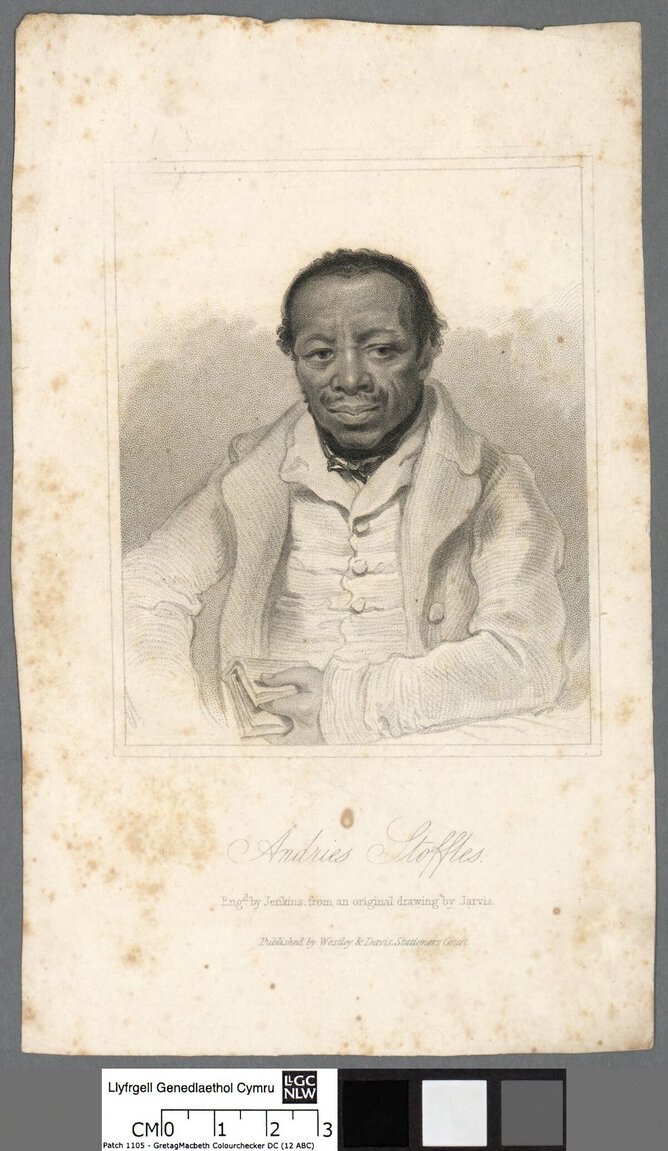

Andries Stoffels (c. late 1770s-1837) was a Gonaqua Khoe and one of the prize converts of the London Missionary Society (LMS) in the Cape Colony in the early nineteenth century. Following the Servant’s Revolt of 1799-1802 along the eastern Cape frontier, Stoffels settled at Bethelsdorp mission station near Algoa Bay. There he came under the influence of the resident missionaries, Johannes van der Kemp and James Read, Sr. Subsequently, Stoffels accompanied several notable missionary explorers and emissaries on their travels in southern Africa, including John Campbell, who conducted a tour of inspection of the LMS’s missions in 1819. In 1829, Stoffels relocated to the newly established Kat River Settlement, situated between the Cape Colony and Xhosaland, where he was appointed a deacon in the church at Philipton.

In 1836, Stoffels was enlisted by John Philip, the superintendent of the LMS in southern Africa, to travel to the United Kingdom to represent the Khoe and to give testimony before the House of Commons Select Committee on Aborigines. He spent several months in the UK, traveling with Philip, Jan Tzatzoe, James Read, Sr. and James Read, Jr. Following his testimony before the Select Committee and an address at Exeter Hall to a gathering of LMS supporters and benefactors, Stoffels returned to the Cape. Due to poor health, he was unable to make the journey from Cape Town to the Kat River Settlement to be reunited with his family and compatriots. Stoffels died in Cape Town in March 1837.

Andries Stoffels’s Background

Early Life Amidst Frontier Volatility

Andries Stoffels (often spelled Stoffles in contemporary writings) was born in the late 1770s (the exact date is unknown) at the kraal (or settlement) of Rinter, a Gonaqua Khoe chief, near the Bushman’s River in the Zuurveld in present-day South Africa. At the time, the Zuurveld, which lies between the Sundays and Great Fish Rivers in the Eastern Cape, was on the fringes of the Cape Colony and of European settlement. Originally inhabited by the Khoe (also Khoekhoe or Khoena), the Zuurveld had come under Xhosa control by the 1770s. Gonaqua (also Gonah or Gona) were Khoe who had intermingled with the amaXhosa for generations and as such, Stoffels had both Khoe and Xhosa ancestries.

The Xhosa presence in the Zuurveld in the late eighteenth century served as a bulwark against expansive European settlement eastwards. Though trekboers (migrant, European stock-farmers) had first entered the Zuurveld in the early eighteenth century, they were unable to establish lasting dominance in the region due to Xhosa resistance. By the time of Stoffels’s birth, contests between the trekboers and amaXhosa over the favourable grazing of the Zuurveld began to escalate, eventually erupting into conflict in the First and Second Frontier Wars (1779-81 and 1793, respectively). Stoffels was thus born into a volatile frontier context that would shape his life in profound ways (Newton-King 1999).

By his early adulthood, Stoffels was in the employ of a Dutch farmer, i.e., a trekboer who had settled in a particular location . He was subjected to harsh, inhumane treatment similar to other Khoe servants in the employ of the Boers, who suffered beatings for even minor infringements. This treatment, along with paltry and unfair compensation, loss of land, and the steady erosion of their independence contributed to growing Khoe discontent in the frontier districts of the Colony. Tensions came to a head in 1799 with the outbreak of the Servant’s Revolt in which scores of disgruntled Khoe servants deserted the colonists’ farms, often with guns and ammunition they had either stolen or had been entrusted with by their masters.

The British colonial authorities – who had seized control of the Cape Colony from the Dutch East India Company in 1795 – were particularly concerned about an alliance between the Khoe and amaXhosa, as such an alliance would have proven a formidable force. The threat that such an alliance posed was to be an ongoing concern for the British at the Cape throughout the first half the nineteenth century. Indeed, the foreboding prospect was realized in the early 1850s with the events surrounding the Kat River Rebellion (1851) and Eighth Frontier War (1850-53).

However, the Servant’s Revolt (1799-1802), in which Stoffels participated as a Khoe rebel, coincided with the Third Frontier War between the Cape Colony and the Xhosa (1799-1803). Hundreds of Boer farms in the frontier districts of the Colony were abandoned and many thousands of cattle, sheep and horses were raided by the Khoe and Xhosa. The Third Frontier War marked the most serious threat to the colonial presence in the Eastern Cape to date. Though a state of calm returned, the region remained volatile (Newton-King 1999).

Residence at Bethelsdorp and the Kat River Settlement

Stoffels lived in Xhosaland for several months following the end of the Servant’s Revolt in 1802. During this time, he resided near the Sundays River practicing a herding, hunting, and gathering subsistence. Upon hearing of the arrival of missionaries across the colonial boundary at Bethelsdorp near Algoa Bay, his curiosity was piqued and he went to investigate the new mission station for himself. Bethelsdorp was one of the first missions established by the LMS in the Cape Colony. Unlike other ventures of a similar nature undertaken by the LMS both inside and outside the official borders of the Colony, the mission managed to grow in size and population, eventually becoming one of the LMS’s flagship missions in southern Africa. It also became a regular stopover for government officials, missionaries, explorers, and emissaries on their travels from Cape Town to the interior (Keegan 2016).

Leading the Bethelsdorp mission at the time of Stoffel’s arrival there in 1803 was the Dutch missionary, Johannes Van der Kemp, accompanied by a young, British assistant named James Read, Sr. Van der Kemp championed an egalitarian interpretation of the Gospel. Contrary to the dominant Calvinist theology followed by many of the Cape’s colonists, he believed that salvation through Christ was for all, including the Khoe, San, and amaXhosa. Van der Kemp, along with his protégé Read promoted conversion, baptism, and literacy, which were typically regarded as the exclusive domain of the white Christian inhabitants of the Cape Colony. Van der Kemp and Read, Sr. were considered radical missionaries by polite settler society, who thought of them as troublemakers upending the Cape’s religious and racial hierarchies, which were closely intertwined (Elbourne 2002).

Read, Sr. first encountered Stoffels during the latter’s first visit to Bethelsdorp. According to Read, Sr., Stoffels was inquisitive about the missionaries and the Gospel, but initially skeptical. It was after a return visit to the mission some time later that Stoffels became more committed to following the teachings of the missionaries. Even so, it was only in 1815 that Stoffels was accepted into the Bethelsdorp church as a member. Thereafter, he became a high-profile convert of the LMS and a promoter of Christianity among the Khoesan and amaXhosa. He also became actively involved in the development of skills and trades among Bethelsdorp’s residents, including shoemaking, wagon making, and ploughing (McDonald 2020).

Owing to his status as a prize convert and prominent member of the Bethelsdorp mission community, Stoffels had opportunities to travel across the Colony and beyond its official boundaries, to visit other missions and to assist missionaries in setting up new stations. In 1819, he accompanied John Campbell on a tour of inspection of the Cape’s LMS missions. Campbell was a Scottish missionary and explorer, and a Director of the LMS. He was dispatched to the Cape to investigate the LMS’s standing, finances, and growth prospects along with the LMS’s incoming, regional superintendent, John Philip. As such, Stoffels found himself in illustrious company.

In 1829, Stoffels was one of the first Khoe settlers to take up residence in the Kat River Settlement, which he described as “the Hottentot’s Land of Canaan.” Located on the eastern Cape frontier around the headwaters of the Kat River, the Settlement was set aside for Khoesan. The British intended that the Settlement would serve as a buffer zone between the Cape’s colonists and the amaXhosa. As a result, many of the Settlement’s early residents relocated there from other LMS’s mission stations, such as Bethelsdorp, Theopolis, and Hankey.

The LMS along with its evangelical-humanitarian supporters hoped that a thriving Christian Khoesan peasantry would become established in the Kat River Settlement. The early inhabitants set about channeling water canals and ploughing fields. Several villages sprung up over the next few years and the population of the Settlement grew steadily. Following his move to the Kat River, Stoffels continued to be a promoter of the LMS’s work and he was appointed a deacon in the church at Philipton. This was one of the Settlement’s most established villages, named in honour of John Philip, with whom Stoffels was well acquainted from their travels together.

The initial optimism surrounding the establishment of the Kat River Settlement and its prospects were short-lived, however. The eastern Cape frontier remained volatile and tensions between the amaXhosa and the colonists were often a spark away from war. The Settlement was caught in the crossfire during the Sixth and Seventh Frontier Wars (1834-35 and 1846-47, respectively), which resulted in damage to property, destroyed crops, and led to the loss of livestock. Many of the Settlement’s residents struggled to rebuild their livelihoods after these conflicts (Ross 2014).

The Historical Context for Stoffels’s Testimony Before the Select Committee on Aborigines

Pleading the Cause of His People

In February 1836, at the approximate age of 60, Stoffels boarded a ship in Cape Town bound for the UK. Stoffels had been recruited by Philip as an ideal representative of the Khoe to appear before the House of Commons Select Committee on Aborigines. The recruitment was due to the former's status as a prominent member of the Kat River Settlement and as a prize convert of the LMS, as well as his extensive knowledge of the Cape interior and its various population groups The Committee had been tasked with investigating the plight of indigenous peoples across Britain’s nascent empire and, in particular, the impact of settler colonialism on their demise. Philip was invited to testify before the Committee in person and to bring with him suitable representatives of the Cape’s indigenous populations. Stoffels and Philip travelled to the UK accompanied by Jan Tzatzoe, the Xhosa chief and missionary and James Read, Jr., the half-Khoe son of James Read, Sr. They were later joined by James Read, Sr. himself.

Stoffels gave testimony before the Select Committee on Aborigines on 27 June 1836. An excerpt of this testimony is now published by One More Voice. Stoffels gave his testimony in Dutch (the language of the majority of the Cape’s colonists, which was continuing to evolve into the distinct, local dialect now called Afrikaans), while James Read, Jr. served as his interpreter. In the testimony, Stoffels responds to questions relating to his life as a resident of Bethelsdorp and the Kat River Settlement, and he provides insights into the social and economic circumstances of the Khoe. The Committee’s members also ask several probing questions concerning frontier relations and the recent war between the colonists and the amaXhosa (i.e., the Sixth Frontier War, 1834-35). In responding, Stoffels draws upon his experience and knowledge of the region and its peoples and so is able to answer in an authoritative fashion.

It may be speculated that Stoffels was coached by Philip and Read, Sr. in how to answer the questions put to him, as well as what themes and matters to emphasize when responding. If so, such coaching was due to the fact that Philip and Read, Sr. saw the Committee as an ideal platform before which to air some of their grievances with the Cape’s colonial authorities, including Sir Benjamin D’Urban, then the current Governor of the Cape. Even so, Stoffels found himself in a rare position, as a representative of his people speaking directly to an official committee of the imperial government at the heart of the metropole. In his answers, therefore, he uses the opportunity to espouse the contributions of the missionaries in assisting the Khoe to secure civil rights and to find a semblance of protection and stability at the mission stations dotted throughout and beyond the Cape Colony.

Stoffels also speaks directly to one of his most pertinent, personal grievances: the ongoing prejudice of the English-speaking colonists towards his compatriots. Stoffels indicates that while he had personally experienced the hostility of the Boers towards his people, he expected the English-speaking colonists from England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales that settled in the eastern Cape in the 1820s to have a more cordial disposition towards the Khoe. In elaborating on this point, he notes the poor treatment that Khoe suffered at the hands of the English colonists, who, like the Boers, tended to pay low wages and who were constantly clamoring for harsher vagrancy legislation so as to coerce more Khoe into labor.

Although it is not clear what impact Stoffels’s testimony had, the Committee’s final report does allude to some of the observations Stoffels made concerning the debilitating effects of settler colonialism on the Khoe, specifically with regards to the loss of land and the poor working conditions they were often forced to endure.

His Return to the Cape and His Death

Stoffels remained in the UK for a few more months along with the other members of the Cape party. During this time, he attended meetings and fundraising events organised by the LMS as well as a session of the House of Commons. In August 1836, he delivered an address – also published by One More Voice – to a packed Exeter Hall in London, which had previously hosted gatherings of the Anti-Slavery Society and so had become associated with the evangelical-humanitarian movement. Again, speaking in Dutch and again translated by James Read, Jr., Stoffels uses the address to relay the grievances of his people as well as his own gratitude for the efforts of the missionaries to aid the Khoe. By this point, Stoffels had gained a reputation for being a fine orator among the inhabitants of Philipton. In London, he clearly struck a chord with the audience, with the MP Edward Baines describing the former’s speech as “sublime.”

When read alongside Stoffels' testimony to the Select Committee, it appears likely that his address to Exeter Hall was edited and embellished before publication in the Missionary Magazine and Chronicle. It is not clear whether Stoffels was aware that he would be called upon to address the special general meeting of the LMS and if he had prepared a speech or notes beforehand. The flow of ideas and general lucidity of the speech suggests that he had been prepared. Nonetheless, the number of grand claims extolling the virtues of the LMS and its missionaries, as well as the absolutist tone of many of its observations, suggests that a fair degree of editing occurred before the speech's wider dissemination through the periodical. Given that Stoffels' address was delivered in Dutch and translated by James Read, Jr., it is also plausible that someone more adept in the English language emended the text, so as to reflect more of a colonial point of view. It was not an uncommon practice at the time for the British editors of such publications to edit for impact, emotive effect, and imperial perspective, and the piece should be read in this light.

While Philip, Read, Sr. and Tzatzoe would remain in the UK for several more months, Stoffels departed for the Cape in November 1836 accompanied by James Read, Jr. Stoffels was suffering from poor health, and so it was considered wise for him to return to his home at Philipton. Stoffels and Read, Jr. arrived in Cape Town in January 1837, after undertaking the two-month sea voyage from the UK. However, Stoffels’s health continued to deteriorate, and he became too ill to make the journey with Read, Jr. from Cape Town to Algoa Bay. In March 1837, Stoffels passed away in Cape Town. It is recorded that on his deathbed, Stoffels voiced regret at not being able to reunite with his family and compatriots in the Kat River Settlement as it was his hope to share all that he had witnessed and experienced during his travels (Levine 2011).

Works Cited/Further Reading

Anonymous. 1838. “Brief Memoir of Andries Stoffels” (PDF). The Missionary Magazine and Chronicle, Relating Chiefly to the Missions of the London Missionary Society 23 (April): 49–52. Courtesy of Special Collections SOAS Library.

Elbourne, Elizabeth. 2002. Blood Ground: Colonialism, Missions and the Contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799-1853. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Keegan, Timothy. 2016. Dr. Philip’s Empire: One Man’s Struggle for Justice in Nineteenth Century South Africa. Cape Town: Zebra Press.

Levine, Roger S. 2011. A Living Man from Africa: Jan Tzatoe, Xhosa Chief and Missionary, and the Making of Nineteenth Century South Africa. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press.

McDonald, Jared. 2020. “‘The Bible Makes All Nations One’: Biblical Literacy and Khoesan National Renewal in the Cape Colony.” In Chosen Peoples: The Bible, Race and Empire in the Long Nineteenth Century, edited by Gareth Atkins, Shinjini Das, and Brian H. Murray, 167–85. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Newton-King, Susan. 1999. Masters and Servants on the Cape Eastern Frontier. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ross, Robert. 2014. The Borders of Race in Colonial South Africa: The Kat River Settlement, 1829-1856. New York: Cambridge University Press.