Overview

Jan Tzatzoe (also Dyani Tshatshu, c.1792-1868) was a chief of the amaNtinde lineage of the amaXhosa in southern Africa who became a prize convert and missionary of the London Missionary Society (LMS). Tzatzoe spent part of his childhood at Bethelsdorp mission station, one of the first mission stations established by the LMS in the Cape Colony, where he was influenced by the controversial missionary, Johannes van der Kemp, and mentored by James Read, Sr., Van der Kemp’s assistant. Nonetheless, Tzatzoe maintained close ties with his family and people, and so became caught between the worlds of the amaXhosa chieftaincies of the eastern Cape frontier and the evangelical-humanitarian missionaries and campaigners of the LMS.

In the mid-1830s, Tzatzoe travelled to England and Scotland where he testified before the House of Commons Select Committee on Aborigines and gave addresses at churches and fundraising gatherings. As such, he was exposed to the life and culture of the colonial metropole to an extent unique among his people. However, following the War of the Axe (Seventh Frontier War) of 1846-47, Tzatzoe’s loyalty to the Crown and the cause of evangelical-humanitarianism came into question, such that by the time of his passing he was alienated from the LMS. Upon his death in 1868, he had also witnessed the entrenchment of British colonial domination over the eastern Cape and the amaXhosa.

One More Voice publishes two letters by Tzatzoe to the Directors of the London Missionary Society. The first letter was written in September 1838 and recounts Tzatzoe’s safe return to his people at the Buffalo River following his time in the United Kingdom. The second letter dates from October 1845 and conveys Tzatzoe’s concerns for his children and their education, among other disillusionments.

Jan Tzatzoe’s Background

Growing Up Between Two Worlds

Born in Xhosaland in 1792, Jan Tzatzoe was the first son of his father’s “Great Wife” and the heir to the chieftaincy of the amaNtinde, a lineage of the amaXhosa. As a prince destined to inherit his father’s title, Tzatzoe was born into a position of influence among his people. His early life would have a profound effect on how he came to fulfil his birthright.

Tzatzoe grew up amidst the ongoing tensions and regular conflicts that characterized European settlement in the eastern Cape region of present-day South Africa. In this context, his father, Chief Kote Tzatzoe, realized the potential value of a mission education for his son and heir. In 1804, at the age of 12, Tzatoe was entrusted to the care of Johannes van der Kemp and his protégé, James Read, Sr., resident missionaries at the newly established Bethelsdorp mission station near Algoa Bay.

Van der Kemp was a controversial figure. He embraced an egalitarian vision of Christian mission and challenged the dominant Calvinist theology at the Cape that considered the region’s indigenes as fated to heathenism and beyond redemption. Van der Kemp provoked alarm among the European-descended settlers by teaching the Khoesan residents of Bethelsdorp to read and write. He also baptized Khoesan converts (Elphick 2012).

Tzatzoe became especially close to James Read, Sr., Van der Kemp’s much younger apprentice. Tzatzoe lived in the Read household at Bethelsdorp and, in 1811, was present when Elizabeth Valentyn, the Khoe wife of James Read, Sr., gave birth to James Read, Jr. Both Tzatoe and Read, Jr. would become high profile members of the LMS in southern Africa. As the son of an English missionary and a Khoe convert, Read, Jr. was born a liminal figure by virtue of his mixed-race heritage. Similarly, as the first member of Xhosa aristocracy to live among Europeans for an extended period, Tzatzoe would grow up co-inhabiting the often contradictory worlds of the amaXhosa chieftaincies and the European missionaries (Levine 2011).

From Heir to Prize Convert

During his childhood and adolescence Tzatzoe obtained literacy and learned Dutch and English. He also developed a variety of artisanal skills, including masonry and carpentry. He was baptized at Bethelsdorp in October 1814, a significant symbolic moment in his transition from Xhosa chief to prize convert of the LMS and its evangelical-humanitarian sympathizers and supporters. His mission education, coupled with his artisanal skills, positioned him as an ally in the LMS’s efforts to expand its mission footprint in the eastern Cape and across the colonial frontier in Xhosaland.

By his early adulthood, Tzatzoe had become active in mission work, proving his value as a cultural intermediary. In the early 1820s, he assisted the LMS missionary John Brownlee in establishing the Chumie mission station in Xhosaland. Tzatzoe’s mission work saw him expand his already notable network among the evangelical-humanitarian lobby at the Cape. John Philip, superintendent of the LMS in southern Africa, took a keen interest in Tzatzoe and the influential role he could play in the LMS’s plans for expansion in the region.

In 1826, Tzatzoe, accompanied by Brownlee, travelled to the Buffalo River, to a large village headed by his father, Kote Tzatzoe. He had returned to his people to establish a mission amongst them. However, he soon came into conflict with some of his father’s councilors when he, Tzatzoe, rebuked his father and the amaNtinde for continuing to follow cultural and spiritual practices he considered witchcraft and against the principles of his Christian faith (Levine 2011).

Nonetheless, over the next several years, Tzatzoe continued to itinerate and evangelize – and challenge rainmakers and prophets – along the Buffalo River. Together with the German missionary, Friedrich Gottlob Kayser, Tzatoe also assisted with the translation of numerous passages of scripture from Dutch and English into isiXhosa (Levine 2011).

It was during his time at the Buffalo River that the government of the Cape Colony established the Kat River Settlement as a buffer zone between the Colony and Xhosaland. Many of those who took up residence in the new settlement were Khoesan who relocated from Bethelsdorp and other prominent LMS missions, such as Theopolis and Hankey. However, the colonial boundary remained porous and was regularly traversed by European and Cape settlers. During the early to mid-1830s, the Xhosa chieftaincies were also increasingly accused by frontier farmers of livestock theft and cross border raids (Price 2008).

Caught Up in Frontier Conflict

In this context, tensions on the frontier erupted in the Sixth Frontier War in 1835, during which the paramount chief of the amaXhosa, Hintsa, was executed by a group of British officers and local Cape soldiers. Initially, Tzatzoe encouraged the amaNtinde to remain neutral, an act that attracted the ire of the Cape’s European settlers. However, Tzatzoe would eventually participate in the conflict, serving on the British side and proving valuable in recapturing livestock that had been raided by the Xhosa. These actions drew the disapproval of key figures in the LMS, including Philip and Read, Sr., as they considered the actions of the amaXhosa to be justified (Mostert 1992).

In the aftermath of the Sixth Frontier War, Benjamin D’Urban, the Cape Governor, extended the official colonial boundary eastwards to the Kei River. He did so by annexing a large swath of Xhosa territory (renamedQueen Adelaide Province) and bringing it under British control. D’Urban’s plans were short lived however, as the annexation of Queen Adelaide Province was rescinded several months later by Lord Charles Grant Glenelg, head of the Colonial Office and an ally of the evangelical-humanitarian movement (Keegan 2016).

From Prize Convert to Ambassador

Meanwhile, in London, there had been growing concern among humanitarian liberals for the plight of indigenous peoples as a result of British settler encroachment across the expanding empire, from Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) to Canada, India, and the Cape Colony. In response to these concerns, a House of Commons Select Committee was established to investigate the treatment of indigenous peoples in Britain’s colonies. Much of the impetus for the Select Committee stemmed from humanitarian MP, Thomas Fowell Buxton, who was a close associate of John Philip. Buxton had particular concern for the effects of settler colonialism on the inhabitants of southern Africa, which was to become a prominent focus of the Committee’s work.

In the Cape Colony, in early 1836, Philip received word from the Directors of the LMS that he should travel to London to give testimony before the Select Committee. He was encouraged to bring an African witness with him. Tzatzoe was chosen to accompany Philip, along with a prominent Khoe leader from the Kat River Settlement, Andries Stoffels, and James Read, Jr. The latter’s father, James Read, Sr., would travel separately and joined the group in London a few months later.

Tzatzoe now found himself in the role of an ambassador of his people. Between 20 and 27 June 1836, Tzatzoe testified before the Select Committee for two and a half days. He responded to questions around the recent Sixth Frontier War (or Hintsa’s War) as well as the general state of affairs of the frontier region. Tzatzoe also recounted his personal history and his long-standing connection to the LMS dating back to his years at Bethelsdorp under the tutelage of Van der Kemp. He explained to the Committee members that he appeared before them as a missionary and a chief. He also regarded himself as a legitimate ambassador representing the Xhosa chiefs and their grievances, especially in regard to frontier relations and colonial encroachment on Xhosa territory (Levine 2011).

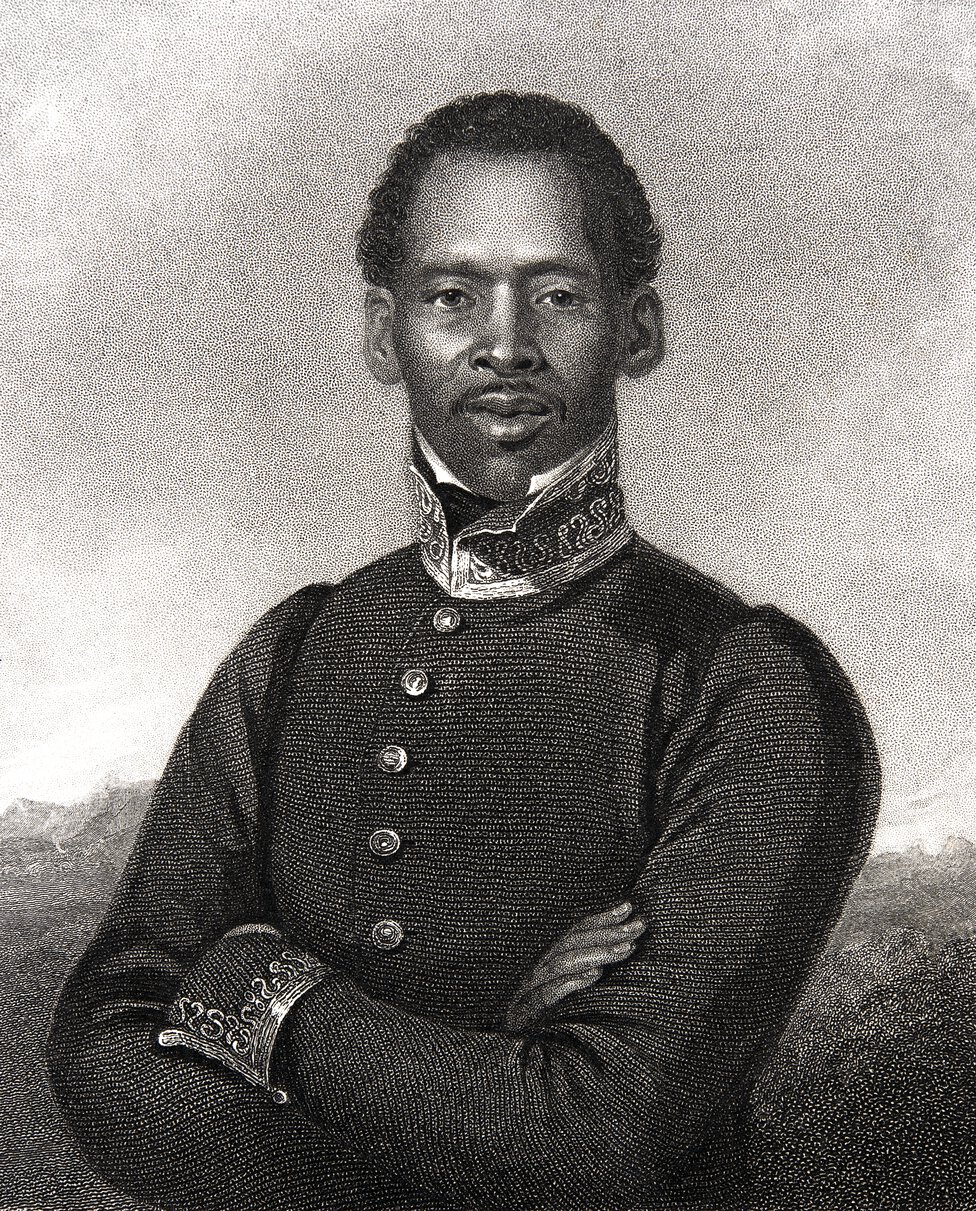

Following their testimonies before the Select Committee, the LMS commissioned a painting of the party. Thereafter, the party travelled across England and Scotland for several months, addressing church audiences and fundraising events organized by the LMS. In August 1836, they attended a session of Parliament and a special general meeting of the LMS in Exeter Hall where Tzatzoe addressed the crowd along with Stoffels and Read, Jr.

The Historical Context for Tzatzoe’s Letters to the Directors of the London Missionary Society

Triumphant Return Home After His Journey “over the great water”

After testifying before the Select Committee in 1836, Tzatzoe, Philip and Read, Sr. remained in the UK and revisited the Committee to observe its proceedings. As a result, the three men (Read, Jr. and Stoffels had parted for the Cape in late 1836) were present in the UK in June 1837 when King William IV died and Queen Victoria ascended the throne. Tzatzoe eventually departed for the Cape in November 1837 along with Philip and Read, Sr., and disembarked in Cape Town three months later.

In September 1838, in the first of the letters published by One More Voice, Tzatzoe wrote to the Directors of the London Missionary Society to inform them of his safe return to the Buffalo River and his people. Tzatzoe’s testimony before the Select Committee had proven impactful, as did his appearances at numerous LMS events. In the letter, Tzatzoe appears to have been aware of his heightened status, noting that he had also relayed a personal message from Lord Glenelg to the other Xhosa chiefs following his return to the Cape.

He also recounts how his people were pleasantly surprised by the warm treatment he had received “over the great water.” Tzatzoe relays that he found his wife and children “quite well,” which was a relief given his two-year absence. He also shares the news that the “Lord is blessing [H]is work” among the amaNtinde and that Brownlee has baptized “two young chiefs,” Tzatzoe’s first cousins.

Tzatzoe uses the opportunity of his writing to the Directors of the LMS to encourage them to support schooling among his people, noting that it is his conviction that education was necessary for the spreading of the Gospel. In Tzatzoe’s view, the infant, secondary, and day schools in operation among his people require better resourcing and more teachers. He also calls for more mission stations to be established in the region. In sum, the letter relays a sense of optimism about future relations between the amaXhosa and the Cape Colony, and Tzatzoe is hopeful that peace can be maintained along the frontier.

Concern for His Children and Other Disillusionments

The expansion of schooling for the amaXhosa was a cause that Tzatzoe continued to campaign for in the years after his return from the UK. This is apparent in a letter he wrote to the Directors of the LMS in October 1845, which is also published by One More Voice. In the letter, dated 8 October 1845, Tzatzoe expresses particular concern for the education of his own children. He notes that it has been his desire to send his children to a good school outside Xhosaland, perhaps owing to his own experience of being mission educated at Bethelsdorp and being conscious of the opportunities this had afforded him.

However, due to a shortage of suitable schools and his inhibiting financial situation, he continues, he is not able to provide an education for his children in the manner for which he had hoped. Tzatzoe adds that his concern for the fate of his children has been amplified by the fact that two of his sons have adopted what he termed the “customs of our heathen [ancestory].” In his view, this has done “great injury” to the cause of God and mission among his people.

Tzatzoe does not elaborate on the Xhosa customs embraced by his sons. The tone and wording of the letter, however, convey a feeling of personal sorrow and a profound sense of disappointment at the behavior of his sons. He describes his anxiety in wanting to relocate his younger children away from any possible negative influence. Such points allude to the extent to which Tzatzoe had immersed himself in his Christian faith, eschewing the traditional and spiritual practices of his people – at least in correspondence with the Directors of the LMS. More generally, the letters suggest that Tzatzoe, as a prize convert caught between two cultural worlds and with a colonial persona to uphold, was often forced to make difficult choices, sometimes between his family and his Christian beliefs.

While a tenuous peace had held along the frontier since the conclusion of the Sixth Frontier War in 1835, tensions were rising once again at the time that Tzatzoe wrote to the Directors in 1845. Part of his anxiety about the future of his children may be attributed to this wider context. The tensions erupted in the Seventh Frontier War (or War of the Axe) in mid-1846 that lasted until December 1847 (Mostert 1992).

Tzatzoe blamed the colonial government for the outbreak of the new war and joined the Xhosa forces in an early confrontation with the British at Fort Peddie. He would subsequently express his opposition to British colonial policies on the frontier, also noting his personal grievances at being unfairly compensated for his missionary work. The letter of 1845 thus foreshadows a general sense of disillusionment and frustration that would overcome Tzatzoe in subsequent years.

Postscript

A short-lived cessation of hostilities on the eastern Cape frontier followed the Seventh Frontier War with the Eighth Frontier War (or Mlanjeni’s War) commencing on Christmas Day in 1850. This was the most destructive and prolonged of all the frontier wars between the Cape Colony and the amaXhosa. Tzatzoe was later implicated in providing ammunition and information to the Xhosa forces during the war. A government inquiry eventually determined that he and the amaNtinde actively participated in the conflict against the British.

Subsequently, Tzatzoe witnessed the disastrous effects of the Xhosa Cattle Killing of 1857 and the entrenchment of British colonial domination over Xhosaland. By this time, he had lost his standing in the LMS and could no longer count on the support of his allies, such as Philip and Read, Sr. who had passed several years earlier. Furthermore, the evangelical-humanitarian lobby no longer held influence on colonial affairs as it had in the 1820s and 1830s, having been eclipsed by a more racially chauvinistic and expansionist colonial project (Keegan 2016). As a result, Tzatzoe found his efforts to advocate on behalf of the amaNtinde, and amaXhosa in general, considerably limited during these years. He spent the remainder of his life in Qonce (formerly King William’s Town) where he died in February 1868.

Note: One More Voice publishes one additional item by Tzatzoe, a letter that he co-authored with John Philip and James Read, Sr. in July 1837, shortly before their departure from the UK. The present essay does not discuss this letter, in which the three men appeal to the “friends of the Hottentot race in the United Kingdom” for financial support for the envisioned settlement of Khoesan at the Great Fish River. The letter is worth consulting, however, because it illuminates Philip’s continuing ambitions to settle the eastern frontier with Khoesan aligned with the LMS and loyal to the British Crown. The establishment of a new settlement of Christian Khoesan along the Great Fish River – in the mould of the Kat River Settlement – was believed to be in the interests of peace along the eastern frontier.

Works Cited/Further Reading

Elphick, Richard. 2012. The Equality of Believers: Protestant Missionaries and the Racial Politics of South Africa. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Keegan, Timothy. 2016. Dr. Philip’s Empire: One Man’s Struggle for Justice in Nineteenth Century South Africa. Cape Town: Zebra Press.

Levine, Roger S. 2011. A Living Man from Africa: Jan Tzatoe, Xhosa Chief and Missionary, and the Making of Nineteenth Century South Africa. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press.

Mostert, Noel. 1992. Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa’s Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People. London: Jonathan Cape.

Price, Richard. 2008. Making Empire: Colonial Encounters and the Creation of Imperial Rule in Nineteenth Century Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.