Overview

Between 2021 and 2023, scholars and students from One More Voice (OMV) and COVE worked in collaboration with Special Collections, SOAS Library and Adam Matthew Digital (AMD) to identify, document, encode, publish, and critically study a series of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) voices from Victorian missionary periodicals. This initiative takes the title “BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press” (henceforth, “BIPOC Voices”).

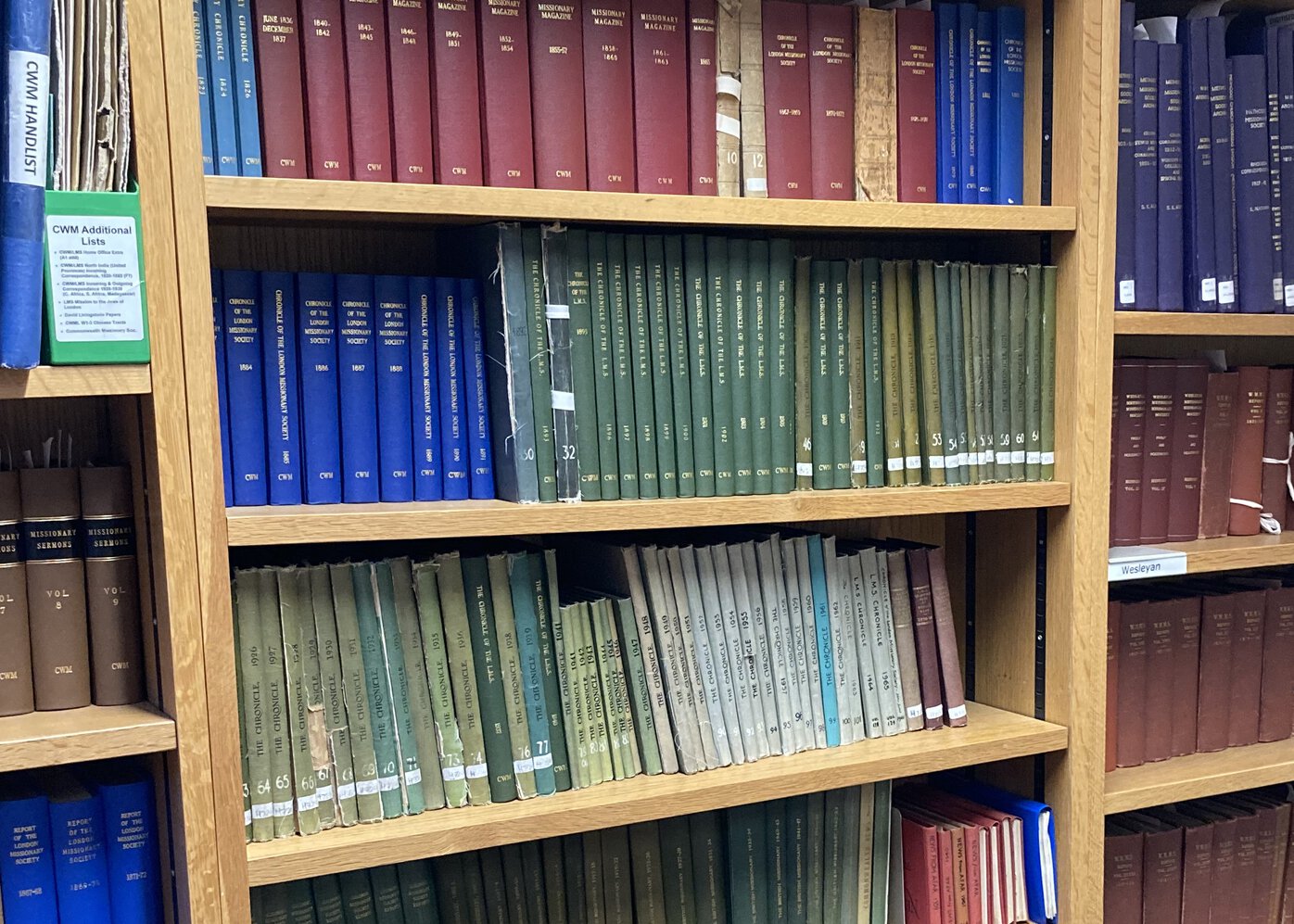

The work evolved through two branches of endeavor, one funded by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) and centered on the physical print holdings of SOAS, the other funded by the Research Society for Victorian Periodicals (RSVP) and centered on the digital holdings of AMD. Both branches focused on missionary periodicals because such periodicals offer an excellent opportunity for engaging with a wide range of Victorian-era representations of BIPOC voices due to the global nature of missionary work. The present publication presents the main findings and outcomes of this collaborative work.

Project Findings

Our project demonstrates that BIPOC voices appear in considerable numbers in Victorian missionary periodicals. As elaborated below, we identified and documented 250+ such voices between the two branches of our project. These voices represent an important, little-studied primary source. The voices, in the words of the One More Voice “Mission Statement,” offer glimpses of “perspectives that scholarship in majority has hitherto overlooked or silenced” and so promise “to transform our understanding of imperial and colonial history and literature.” This potential – alongside the wide array of cultures and ethnic groups involved and the many social strata within the cultures documented – makes these voices worth studying.

Yet our work with these voices over the nearly two years of the project has also revealed that any sort of critical or casual engagement requires extreme caution. Among other challenges, the wording of relevant pieces often suggests that missionary periodical editors and others reduced or otherwise curtailed the textual control of BIPOC creators considerably. Relevant pieces advance points that diminish the BIPOC individuals who are speaking and their cultures. Key ideas clearly reflect British imperial and colonial ideologies of the time rather than the actual perspectives of the BIPOC creators. These circumstances create a real danger that readers will read the BIPOC texts at face value, without recognizing that the racist and otherwise ideologically suspect elements of such texts do not necessarily represent the real views of the BIPOC creators.

In response, our project urges readers to consider that the periodical pieces do not necessarily reflect the views of BIPOC creators – if the creators had any role at all in establishing the final, published texts. Rather, we recommend that readers approach the texts cautiously as offering instances in which the BIPOC creators foremost are being represented by others, especially the British missionaries and periodical editors directly involved in the process of editing and publishing these texts. Moreover, such British-led intervention often occurs silently, without notice to readers or any obvious markers in the text.

Consequently, we believe that a small-scale analytical approach, such as the one we have taken through our project, promises to yield the best results due to the need for a detailed critical approach in engaging with these texts. Based on our project, we also believe that a staged process works best when taking up the work of BIPOC creators in periodicals. Such a process, ideally, combines the critical expertise needed to read these works as products of the Victorian missionary press and the cultural expertise required to engage with these pieces as associated with a variety of globally-distributed, racially-minoritized peoples. Our project, through its essays and overall critical intervention, thus aspires to take some initial steps towards modeling an appropriate, mindful process of engaging with these voices while being aware of the many source text limitations.

Project Outcomes

Over its nearly two years of endeavor, our project brought together two dozen established and early career scholars plus other professionals in the academic and commercial sectors. By the standards of other digital humanities projects, we had limited funding between our two grants ($27,500 from RSVP; $15,000 from UNL; $42,500 total). However, fiscal prudence combined with experienced project management enabled us to maximize the impact of this funding. All established scholars contributed their time to the project pro bono, and, as a result, we directed all our funding to supporting the labor of graduate students and contingent faculty. We also enabled the professionalization of our graduate students to an exceptional degree through extended mentoring in every project phase.

Due to these practices, “BIPOC Voices” has produced a series of significant outcomes, as follows:

- We identified, documented, and created full metadata for 250+ primary BIPOC source texts from Victorian missionary periodicals plus another 100 relevant contextual pieces. Two spreadsheets – one for SOAS periodicals, the other for RSVP periodicals – document this metadata.

- We collected nearly 1000 images of all the identified primary and contextual items in SOAS periodicals. Likewise, we worked with AMD to gather PDFs of all the relevant pieces from its digital holdings. We also assembled all these materials into a fully documented and structured collection. Although the publishing practices of both OMV and COVE preclude the hosting and publishing of this image collection online, it remains available behind the scenes to inform our future efforts. In terms of the SOAS materials, we can also make the collection available on a case-by-case basis for scholars with legitimate research interests.

- We created rigorous digital editions of 64 of the most important pieces identified and documented by our project. 18 of these come from SOAS periodicals; 43 derive from AMD periodicals; 3 are “bonus texts” from other online sources. OMV now publishes these in full, while COVE will provide access to a curated subset of them.

- Over the summer of 2022, project scholars and graduate students developed a series of eight critical essays and two annotated bibliographies on the BIPOC pieces. This critical work seeks to introduce the periodical pieces to a wider audience while modeling informed and intentional engagement with the pieces. We have taken each of the essays through a rigorous process of peer review (PDF | Word) that involved both internal and external reviewers.

- Our work with SOAS and, separately, AMD also produced two formal sets of recommendations. We direct the first (PDF | Word) towards scholars who might take up archival research similar to ours and the second (PDF | Word) to digital publishers who seek to foreground relevant periodical pieces among their digital holdings. Collectively, these recommendations articulate and crystalize the many critical findings that we developed through our work with the BIPOC periodical voices.

- Purdue University’s School of Interdisciplinary Studies provided as cost-share a 0.5 FTE research assistant who focused on encoding a collection of BIPOC-centered texts (see COVE's “Works by and about People of Color” collection). The partnership was successful enough that Purdue has now agreed to extend the research assistantship through the next two academic years (2022-23, 2023-24). Such work provides important contextual material for the texts from “BIPOC Voices” and embodies an important resource in its own right.

Beyond these primary outcomes, our project also led to a set of “bonus” outcomes, i.e., outcomes that we did not anticipate when we submitted our original grant applications. These additional outcomes include the creation of a small corpus (64 files) based on the encoded transcriptions created by our project. This new corpus now stands alongside and so supports the existing corpus of Africa-centered materials published by OMV. Our outcomes will also include, ultimately, the dual publication of project essays and transcriptions on OMV and COVE, due to our ability to leverage parallel coding practices for the two projects. This dual publication promises to extend significantly the use of and potential audiences for our project publications.

The creation of the present integrated “BIPOC Voices” publication via OMV also represents a bonus outcome and means that we now can make all our project results available in one place, in a way that enhances the results of each individual project in relation to the other. Finally, very recent grants, first, from the U.S. National Endowment for the Humanities ($350,000) to support a large-scale redevelopment of COVE and, second, from the American Council of Learned Societies ($25,000) to fund a new partnership between OMV and the Ardhi Initiative mean that the collaborative practices and workflows developed through our current project will serve as prototypes for these new funded initiatives – more so as “BIPOC Voices” involved the leadership of COVE, OMV, and the Ardhi Initiative.

Conclusion

All told, our project of nearly two years has been a success. Through this work, we have established and/or strengthened the partnerships among the main project stakeholders – OMV, COVE, SOAS, and AMD. We have found multiple ways to extend the missions of OMV and COVE, including supporting the efforts of underserved segments of the academic population, promoting open-access publication, and fostering intentional, antiracist critical engagement. Finally, we have continued a process begun through prior project initiatives of widening the global engagement of both OMV and COVE since “BIPOC Voices” brought together scholars from Britain, Canada, India, Kenya, South Africa, and the United States.

We invite you to engage with our project materials and/or to reach out to us if you’d like to discuss the outcomes of our work or become involved with the efforts of OMV and COVE.