- Overview

- Nineteenth-Century Southern African Scribes

- In/Authenticity

- In/Consistency

- Re-membering

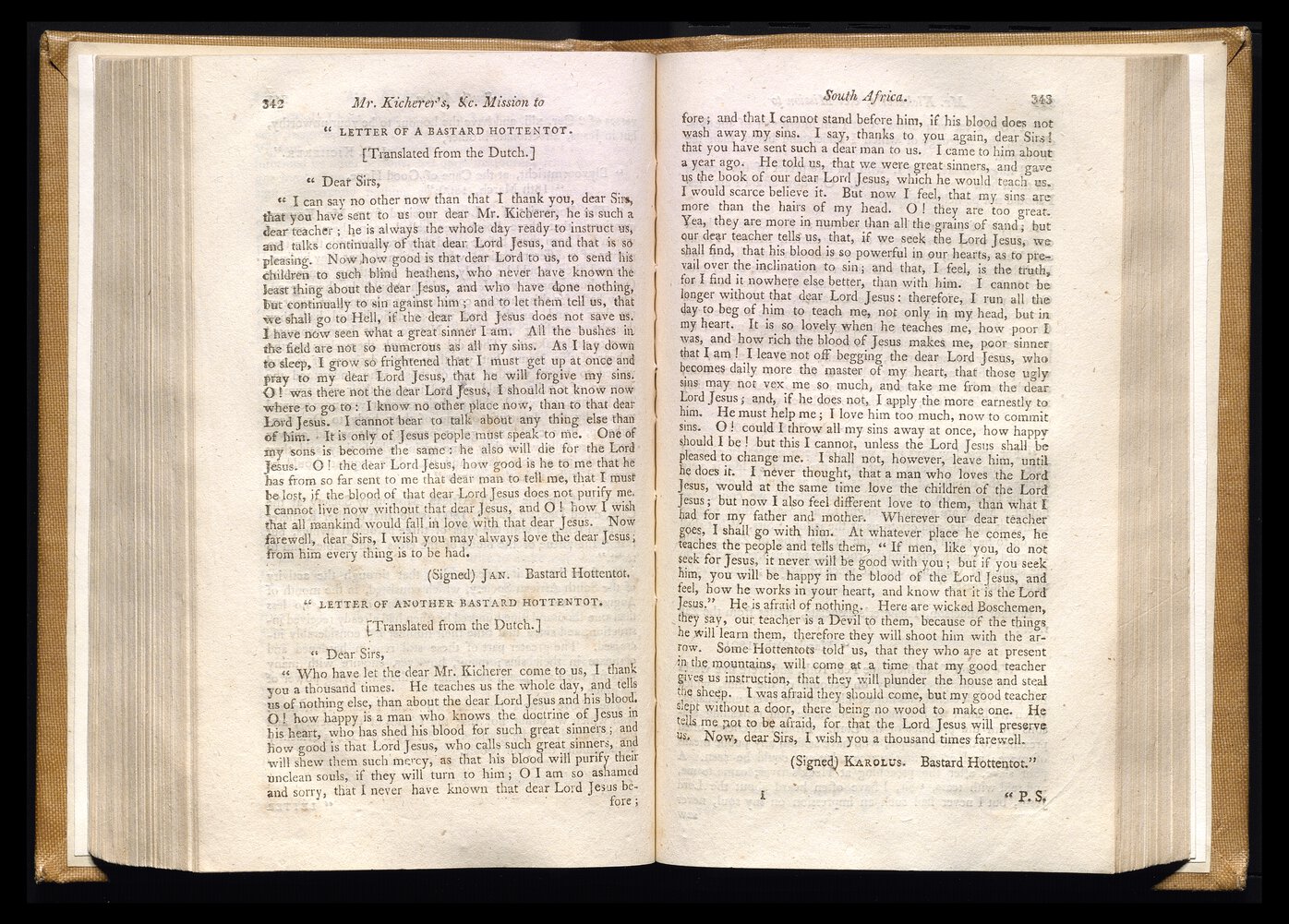

- Jan and Karolus

- Narrative Framing

- Translation from the Dutch

- Postscript as Redolence of Self

- Reverend Charles “Chaz” Pamla (also Sep[h]amla)

- Narrative Framing

- Pamla’s Letters

- Repetition as Redolence of Self

- Conclusion

- Citation Practices in this Essay

- Works Cited

- Page Citation

- Lead Image Details

Overview

This essay examines the letters of three southern African authors published in the nineteenth-century periodicals of the London Missionary Society (LMS) and the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (WMMS). These periodicals served as the focus of “BIPOC Voices from the Victorian Periodical Press” (henceforth “BIPOC Voices”), an initiative to identify the largely-unstudied BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) creators found in these periodicals. Indexes and catalogues of relevant archival holdings also usually exclude writers of these documents. The “BIPOC Voices” project, therefore, sought to redress and reverse these invisibilities by critically remediating specific voices and by providing access to a small selection of documents.

The first two scribes I shall discuss are Jan and Karolus, Christian converts and translators from the south-eastern coast of Africa. Their letters to the LMS appear together in the very first volume of its first periodical, The Transactions, in 1804 (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022). These letters evidence the pervasive contributions of BIPOC authors from the very inception of missionary periodicals as a literary genre. This essay then focuses on letters penned by the Rev. Charles Pamla in the early 1870s. Pamla, a Wesleyan Methodist missionary, corresponded with colleagues local to areas around Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth of old) and the Transkei. His letters appeared in Wesleyan Missionary Notices in 1872, whether with his permission or not we do not know (Anonymous, Charles Pamla [1872] 2022). These three individuals all hail from the same part of the south-eastern African coast and inland stretches.

The textual selections for the “BIPOC Voices” project spanned five decades of the nineteenth century, namely 1800-10, 1820-30, 1849-59, 1870-80 and 1900-1910. As lead archival researcher for “BIPOC Voices” I sampled the following LMS periodicals:

- Transactions of the Missionary Society, 1800-1810

- The Missionary Chronicle, 1822-1830

- Missionary Magazine and Chronicle, 1849-1853

- The Chronicle of the London Missionary Society, 1870-1880

- The Report of the Directors of the London Missionary Society, 1870-1880

- Juvenile Missionary Magazine, 1870-1880

I also sampled the following WMMS periodicals:

- The Wesleyan Missionary Notices, 1870-1876, 1903-1904

- The Foreign Field of the Wesleyan Methodist Church, 1907

- Women’s Work, 1907-1910

- Work and Workers in the Mission Field, 1900-1910

During this research, I identified over 200 letters, reports, prayers, speeches, proclamations, and petitions represented as written by BIPOC authors together with excerpted texts included within other reports and letters. These texts, written at different moments in the nineteenth century, provide information about members of Christian communities as well as the development of Christianity in Africa. These findings reinforce Arun W. Jones’ assessment that “the idea that indigenous Christians have been unable to leave a historical record of their voices and activities is simply not true [...] [T]he important question [...] is not how to discover and uncover native Christian voices but whether one is willing to look at materials produced by indigenous Christians and other persons, and work with these materials” (2021, 5-6).

Notably, the periodical pages also present an historical record of the voices and activities of contemporary heads of state, thinkers, politicians, and translators who were not Christian. In short, missionary periodicals do not preclude works of BIPOC people who are not Christian converts. Missionary periodicals are, like the schools Rev Emmanuel A.S. Egbunu discusses in his recent book (2021, 17, also see 7), “appendages of the churches,” but “open to all within the community who were not necessarily of the Christian faith.” For example, correspondence between local Southern African leaders Adam Kok and Willem Uithaalder regarding autochthonous African resistance to English settlement appeared in the Missionary Magazine and Chronicle (Anonymous, Adam Kok, and Willem Uithaalder [1851] 2022).

The words of all these individuals provide invaluable detail, including people’s names, social positions, relationships, hometowns, activities, perspectives, and philosophies. In fact, these periodicals provide the opportunity to see a panoply of identities from across the world, a veritable counterculture of nineteenth-century modernity, as described by Gilroy (1993). As such, these periodicals constitute a site of exciting potential for researchers. Learning even just a little about each individual, at least via what is presented and represented in the periodicals, allows scholars to gain a greater understanding of individuals’ communities, broader contexts, and milieus. This in turn also “allow[s] new questions to be asked and new problems to be posed” (Fay, in Aljoe 2012, ix).

Nineteenth-Century Southern African Scribes

In this essay I use the term “scribe” to refer to the individuals whose letters I discuss. This term highlights my objective to accredit the act of inscription to these particular individuals. Only once proved can I inspect the work of message encoding and engage the complicated theoretical dynamics around content and its authoring, authorship, authority, agency and authenticity. Whilst I do hold these theoretical questions as pivotally important, in this essay my focus falls on whether readers can be sure that these men actually put pen to paper in writing the letters themselves. If it were possible to prove pen-personship, then these letters constitute embers of hope which allow for an outline of the knowledge and information for which we search.

Furthermore, if we can prove pen-personship, we can then read these written utterances for that most problematic of theoretical imperatives: evidence of actual self-articulated identity. Beyond the tally of contributors already set out, I hope to enable readings that will reveal details of individual scribes and their traditions, thereby helping to expand the outline of their lives. In this vein, three recent critical works offer excellent research of newly retrieved archival resources. Jones (2021) and Aljoe, Carey, and Krise (2018) highlight research analysing the documents and sources of racialised people in archival sources, while Mokae and Willan (2021) use research on South African author Sol T. Plaatje to further critical analysis and interpretations of his voice, traditions, and perspectives. These works demonstrate that with enough careful research and analysis, we can expand our knowledge of intellectual history.

This work, including my essay, forms part of a decolonial mission to “acknowledg[e] and affirm[] subjectivities that fall outside the purview of Western modes of thinking and expressions of being” (Hirmer, Istratii, and Lim, 2018, 10-15) and also takes as its cue Steve Biko’s call to reclaim and redeem subjugated Black identities and “correct[...] false images of ourselves in terms of Culture, Education, Religion, Economics” ([1978] 2004, 57; see also 105). I hope this research will become what I call after Karabinos (2018) a “trace archive,” a kind of anticolonial catalogue of documents and sources which were created by racialised authors and are described within other archival sources, but never located (cf. Mimi Onuoha’s work with missing datasets, discussed in D’Ignazio and Klein 2020). For example, Robert Moffat mentions letters by a South African named Andria Seretsé who almost travelled overseas with Moffat, “but feared to do so without the sanction of his father.” Instead, Andria wrote to Moffat in England, who was “wont to receive [Andria’s] letters with no common joy” (Anonymous and Robert Moffat 1849, 60).

This correspondence is not presented in the periodical nor in Moffat’s papers lodged in the Special Collections of SOAS Library. It has never been in existence, as far as we can tell, bar this one mention. A trace archive would note all of these mentions. Scholars could start to imagine alternate versions of history and historiographies that could have developed around that once-extant correspondence and other similar documents. That “trace” reference thus has the potential to contribute towards a transformative revisioning of history and of archival holdings.

In/Authenticity

Even though I am engaged in this search for and recovery of racialised voices, I neither seek nor posit authenticity as a hallmark of voice. Authenticity brings categories and other means of a priori assessment that imply essential and deterministic characteristics (Mercer 1990; 1991). Paul Gilroy (1993, 72-110) debates whether racialised identities are in and of themselves inauthentic. He argues that whilst expressions of Blackness share characteristics globally because of pervasive white supremacist governance structures, racialisation changes according to the needs of colonial governments as do its effects and impacts (72-145, esp. 121-124). None of these expressions, effects, or impacts is authentic or innate to anyone.

The connotative connections between authenticity, tradition, and nationalism also render authenticity unsuitable as a characteristic for reading identity and voice because the people in these notions of authentic traditions are imaginary visions, like an mirage in a desert.

In/Consistency

It is also not advisable to count consistency as a hallmark of self-enunciation. Instead, this essay counts as useful its very opposite: sponteneïty. Black feminist literary critics and identity politics theorists in the late twentieth century asserted the existence of a multiple identity, characterised by myriad and conflicting versions of self within each person; in one lifetime, even in one day, a person can make decisions which are inconsistent and unpredictable. Jones (2021, 9) identifies the importance of polyvalency in early Christian converts whose documents are archived. He accords multilingual and multiracial identities to “persons with origins in disparate communities [who grapple with] more than one religious tradition, more than one culture, and more than one social location.” This multiplicity enabled significant impacts on “intracommunal communications” which in turn led to further social change (9-10).

Similarly, in discussions related to in/consistency of self, post-modernists have long refuted even the possibility of asserting subjectivity in favour of a/the perpetual slippage of meaning. I, however, do not hold to the necessity of this outcome. My true objective is to find a uniqueness of perspective and expression which would confirm the identity of each scribe; I would like to describe this quality as “redolence of self.” This requires the identification of expressions within each document that could not have been written by anyone other than the claimed author. Assessing this is a theoretical minefield and involves significant study of texts, but can nonetheless be done. We may find the actual twinkling of a unique and unpredictable perspective as a result.

Re-membering

Scholars may find this to be too fanciful an academic endeavour. Hartman (2018) argues most persuasively that Black women’s voices are represented in archival holdings through a range of strategies, but not in words; others argue that the archive is a site of debilitation of and violence against these voices: “As a feminist,” notes Bibi Bakare-Yusuf (2018),

I am acutely aware of the violence and injustice of the archive, whether this is from colonial records, European philosophical musings about our ahistoricity and our lack of sophistication because of the absence of gendered pronouns or scientific treatise about our cognitive ability, or indeed Africa’s own oral narratives, philosophies and mythologies, all of which have provided the template for how we are seen and how we see ourselves today.

Indeed, these assessments are inarguably borne out by a lived experience of archival research. For instance, the racialised voices recovered by our project encompass but a tiny fraction of the representations of European voices within the same periodical pages. Meg Samuelson (2007), similarly, outlines a critical strategy of “re-membering” in her work on the position of South African woman Sarah Bartmann within the archive and historiography. Bartmann was called “the Hottentot Venus,” that is, she was identified as a woman belonging to the same ethnic group accorded to Jan and Karolus (see below), who were also associated with members of the various indigenous peoples of southern Africa referenced by the pejorative term of “Hottentot.” In 1810, six years after Jan and Karolus’s letters appeared in print (1804), Bartmann was brought to England and France and displayed as an object of curiosity before, eventually, dying in 1815. Bartmann’s dissected body parts and a plaster cast of her entire body were only repatriated from Le Musée de l’Homme in 2002.

However, Samuelson refuses the idea that a re-membered body can be achieved for Bartmann. Rather, Samuelson stresses that Bartmann continues to endure different castings: from the physical cast made of her body, to the different roles within which she is cast in the building of the new South Africa, to her casting as a “tragic victim” (Ngubane, in Samuelson 2007, 101). Bartmann is always positioned as one to be gazed upon. This highlights the sinister side of owning, ordering, and displaying items according to an imposed agenda in order to evoke particular emotions or readings, and so manipulate the viewer. We should always bear this in mind and be alert to positionality, to abuses of power and privilege, and to lack of self-reflection or critical appraisal.

Yet the many writings the present project has surfaced also prove that colonial archives remain viable sites of scholarship on and for voices of racialised nineteenth-century peoples. Sandiford (2018, 11-12) highlights the importance of retrieving “the membra,” as he advises

a literary history [...] will perform the work of remembering in a very originary sense of the word: it will perform the very patient work of recovering and putting together again the scattered parts (the membra, in the literal Latin etymology) of bodies that primordially reproduced their ontologies and cosmologies through oral, ritual, and artifactual practices, then had these relationships written into European consciousness by European subjects, and still later wrote accounts that attempt to contest, correct, and resist colonial representations, and begin the long process of redeeming their consciousnesses on their own terms.

This is a clarion call to action which this essay heeds in the search for these “scattered” membra.

Jan and Karolus

The letters of Jan and Karolus ([1800]) appear in the second issue of the first volume (1804) of the LMS’s inaugural periodical The Transactions (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022). The local LMS missionary in South Africa, Mr. John Kicherer, had sent their letters to the LMS with his own in 1803. In his introduction to the letters (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022), Kicherer notes the dates he received these two letters as “Dec. 22 and 23, 1800.” Jan and Karolus describe the impact of the doctrine Kicherer espouses on their lives and on their relationships with family members and their broader South African communities. Both men insist on their fervent rejection of those who are not converts. They also praise Kicherer while repeatedly offering their thanks to the LMS for sending Kicherer, and “the dear Lord Jesus,” to them (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022).

The mere fact that these men were literate and penning letters in the eighteenth century presents a rare and exciting newness to the scholarship of this era. The letters permit the possibility that these individuals might enter into dialogue with the LMS and its readers both in Britain and throughout the reach of its global networks. These literary endeavours deliberately set out to impart knowledge of the authors’ lives. The letters show their authors as cognisant of the expectations which form sites of interest to their audience and their being keen to meet those expectations.

Narrative Framing

The Transactions presents the two letters set side by side on two pages, below a header, with one introductory heading for each of the letters. The running header – “Mr. Kicherer’s, &c, Mission to / South Africa” – splits across the left and right pages (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022). This running header reflects the context of the periodical as a whole and presents the South African mission as belonging to Kicherer under the auspices of the LMS. The first introductory heading, “Letter of a Bastard Hottentot,” sets the stage for the first letter (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022). In echo of the heading, Jan’s letter is then signed “Jan. Bastard Hottentot”; Karolus’s letter works in a similar fashion ([1800] 2022, 342-43). The texts are thus both framed, beginning and end, by the words “Bastard Hottentot,” which shows the hand of Kicherer and the LMS in the writing.

The label “Bastard Hottentot” comprises a double derogation. The use of the word “bastard” associates shame with these authors because it signifies issues of lust or “concupiscence” as South African Scottish theorist Zoë Wicomb terms it (1998, 92). The word “Hottentot,” a derogatory label now and in the nineteenth century, is derived from European traders who used the word for people from at least twelve communities in the relevant area of South Africa. Schapera (1930, n.p.) defines these groups as Chariguriqua, Inqua, Kochoqua, Goringhaiqua, Little Namaqua, Hancumqua, Hessequa, Attaqua, Outiniqua, Chainoqua, Gonaqua, and Damaqua. An editor of The Transactions also explains through footnotes that “Bastard Hottentot” means a “mixed breed from Europeans and natives” or “a mixed breed of Hottentots with other nations” (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022).

This racialisation and othering appear to be the most significant characteristic which predicates the entire meaning which Jan and Karolus can present. Yet the label is simultaneously an empty signifier, devoid of meaning. Despite the repetitious racial insistence, the letters do not disclose which, if any, of these thirteen communities were home to Jan or Karolus. The only idea we can assume is that the two men were black or brown skinned because that is what their racialisation infers.

Translation from the Dutch

However, the third heading for Karolus’s letter, “[Translated from the Dutch]” (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022, brackets in original), reassures the reader that, despite these classificatory strictures, Karolus is fluent enough in Dutch to pen a letter in that language. This opens the possibility that Karolus, and perhaps Jan, were literate in other languages, whether African or European, and, potentially, that such literacy would have been a feature of this society more generally.

Postscript as Redolence of Self

In a postscript that appears on the very next page after his letter, Karolus most unexpectedly identifies himself as an interpreter and refutes the racial categorisation of “Hottentot.” He writes:

P.S.—I let you know, that I am interpreter of the Boschemen, the language of which I understand better than the Hottentot.

I forgot to say, that I, who am interpreter of the people, tell them how they can be helped. O! how afraid I am, lest I should not be helped myself. (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022)

The first part of the postscript destabilises the attributions of race of the previous page. Karolus mentions that he is more confident with the language of another indigenous group based in southern Africa, which he calls “the Boschemen,” i.e., the “Bushmen,” a pejorative term that was used to refer to the San peoples of the south-east African regions. This calls into question Karolus’s home language and home community.

The specific wording of the passage lends itself to the idea that both of these named languages could be second languages for Karolus. His expression, “the language of which I understand” (Anonymous et al. [1804] 2022), seems to imply that he was not raised in the language of “the Boschemen,” but learned it. Indeed, as we know Karolus to be fluent in Dutch, and as he also claims fluency in two southern African languages, we may even debate whether he hailed from a completely different part of South Africa, or southern Africa such as Maputo or Angola, or anywhere within Dutch trading zones.

That the post-script is included at all when it performs such a destabilisation implies at least one of two possibilities. Firstly, the editors of Transactions may have considered that Karolus himself might read the article and notice an infelicitous reproduction of his words. Secondly, the editors did not perceive the contradiction and resultant destabilisation, which implies that their knowledge of the system of racial classification was itself impoverished. The effect of this destabilisation is to cast all the information in the letter in a new light, requiring us to consider each aspect of it anew.

The unique nature of the postscript points to the quality of “redolence of self” that I introduced earlier and suggests that Karolus has at the very least contributed to the writing of this particular letter. Through the postscript, the system of imposed racialisation signalled through the title and signature of the letter is destabilised. Who else might have accorded a different name to Karolus’s racialised identity? Who else might have introduced this possibility of inconstancy: the missionary editors, scribes, or translators? None of these individuals seems a likely candidate because the identity reference contradicts the text of the letter’s title.

Furthermore, Karolus’s self-characterization as an interpreter bears significance. Contemporary scholars of Christian history routinely seek information about polyglot interpreters and translators who enabled the cross-social transmission of religious and other cultural information and doctrine (Brock et al. 2015; Fuchs, Linkenbach, and Reinhard 2015; Jones 2021; Bessong, Prosper, and Kenmogne 2007).

Now scholars can start to trace any further documents in which Karolus is identified and build knowledge of him and, potentially, Jan, since the latter’s letter appears beside that of Karolus in the periodical. This fact, along with the shared backgrounds of the two men, points to other affinities between them. There will also be instances in which Karolus and Jan are noted and which record references to others with whom the men interacted or who formed part of the men’s specific cultural context. Scholars can thus start to account for Karolus and Jan and to restore these men and their experiences to the historical record.

Reverend Charles “Chaz” Pamla (also Sep[h]amla)

Three letters accredited to Rev. Charles “Chaz” Pamla (Sep[h]amla), Fingo Wesleyan Methodist minister stationed at the Tsomo River in the Eastern Cape, offer another opportunity to search for redolence of self. These letters appeared in the Wesleyan Missionary Notices in November 1872 (Anonymous, Charles Pamla [1872] 2022). Pamla wrote two to his colleague Rev. Robert Lamplough in May and June 1872, respectively, plus another to Rev. William Binnington Boyce in July 1872.

Narrative Framing

The headings provided by the Wesleyan Missionary Notices focus on the location in which these letters were written – “South Africa” is the title in the running header, with “Graham’s Town District” as its subtitle – and so organise the content for the reader geographically while reflecting the global nature of the missionary endeavour (Anonymous, Charles Pamla [1872] 2022). An anonymous editor introduces Pamla as one of “two of our Native Missionaries in South Africa” (Anonymous, Charles Pamla [1872] 2022). This racialisation particularises Pamla, and the use of capital letters suggests a stable categorisation for Pamla. The anonymous editor also notes that Pamla’s letters “were written in English” (Anonymous, Charles Pamla [1872] 2022). These letters therefore have one fewer layer of fetters on conveying meaning than do those of Jan and Karolus, as noted above.

Pamla’s Letters

In each of these letters, Pamla records similar information. He first reports on the progress of his work in the four months since he started a mission station in the Tsomo River region of the Transkei, south-eastern Africa. He lists buildings built and planned, and he details the development of schools in the areas under his mission station. He also outlines his itinerary routes, positions, distances, and the number of converts. He explains that he is accompanied on his routes by “two preachers, or evangelists, and a few men” (Anonymous, Charles Pamla, [1872] 2022). This is invaluable information for scholars of African Christianity on the development of mission work in this era in this locale.

In the June 1872 letter to Lamplough, Pamla recounts in great detail a mass conversion of “penitents” that follows the conversion of a chief, named in zeugmatic ellipsis as Dingiswayo:

I began my work at the chief Dingiswayo’s kraal, and preached there daily for a whole fortnight. Two preachers, or evangelists, and a few men, accompanied me. Preached night and day. Many heathen were converted, and the chief too, who is a relation of mine. (Anonymous, Charles Pamla, and Boyce Mama [1872] 2022)

Alongside this chief, “two of [the chief’s] sons, and his great wife, and one of his councillors” also “found peace,” Pamla’s unique expression for having converted to Christianity (Anonymous, Charles Pamla [1872] 2022). Pamla explains that his preaching after this public conversion caused many more people to convert and miraculously to found a new church, all in the same afternoon.

Although this description seems hyperbolic and the number exaggerated, it is part of a revivalist trope. Pamla’s May 1872 letter echoes the descriptions of South African Natalian revivalist Methodist meetings in 1866, in which Pamla interpreted for the English-speaking American visitor from the Methodist Episcopal Church, Rev. William Taylor (Anonymous, Charles Pamla [1872] 2022; cf. Balia 1992, 81-83). This echoing involves the repetition of Taylor’s words and must have been very powerful as it was a successful revival.

Pamla’s July 1872 letter to Boyce offers more concise summaries and observations about his gains and successes than his May and June letters to Lamplough (Anonymous, Charles Pamla [1872] 2022). Rather than elaborating on his relationship with Dingiswayo and the new church, Pamla states instead “one native chief and his family has been brought in, and many of his councillors” (Anonymous, Charles Pamla [1872] 2022), using a racialised term to define Dingiswayo. Pamla plays down the significance of Dingiswayo in the mass conversion and omits mention of his relation to Dingiswayo. It seems Pamla seeks to create a distinction between himself and Boyce on the one side, and Dingiswayo on the other. Perhaps Boyce and Dingiswayo had a difficult history and news of Dingiswayo’s conversion would highlight Boyce’s ineffectiveness to the LMS, rather than Pamla’s effectiveness. Perhaps Pamla became irritated at repeating information in different letters to different colleagues and impatient with detail.

All three letters also concern Pamla’s ability to preach and teach in English as well as Xhosa. In each, Pamla includes a short but significant note on his abilities as an English speaker. For example, in his letter of May 1872, Pamla writes, “If I had a little time with you [Lamplough] I should be able to preach in English with ease” (Anonymous, Charles Pamla, and Boyce Mama [1872] 2022). Pamla then notes in his letter of June 1872 that “God has put it into [the Europeans’] hearts that I should preach to them in English, and I have tried, and God has been pleased to bless His Word. God has also moved them to ask me to be their Class Leader [...]” (Anonymous, Charles Pamla, and Boyce Mama [1872] 2022). Whereas Pamla had discerned the hand of God in this English mission in the June 1872 letter, he omits that detail in the letter to Boyce of that July in favour of the will of the Europeans:

I hold a service in English occasionally for the Europeans at their own request. I have formed an English class, which I meet in the Mission house, which is composed of ten members at present. Some of these express their joy now in the Saviour, who have also showed their regret and repentance by coming forward as penitents alone with the natives during the service, and were not ashamed to confess Christ before men. (Anonymous, Charles Pamla, and Boyce Mama [1872] 2022)

Repetition as Redolence of Self

The quality of redolence of self emerges in Pamla’s three letters not through any specific thing he says, but the revisioning and repositioning of his content which, almost through unstable irony, reveal his attitude both to his work and to his readers. As Pamla drafts correspondence for specific audiences, the repetition allows for different ideas to percolate, and different priorities to be foregrounded, thereby constructing the history from different aspects of Pamla’s perspective. In these ways, Pamla asserts his knowledge, linguistic acumen, adaptability, and his ability to cross congregations while ministering to both English and Xhosa speakers. Collectively, these moves offer glimpses of the ambitions, hopes, and practices of the real individual behind these letters.

Conclusion

In this essay I have argued that the letters which Karolus and Jan wrote around 1800 and those which Reverend Pamla wrote in 1872 are all characterised by redolence of self. Through close critical analysis, I identified the letter ascribed to Karolus as redolent of self because it destabilises the very racialised categorisations which delineated the frame for the meanings Karolus might produce as a Black person writing to the LMS. I identified redolence of self in the letters ascribed to Pamla in the strategic practices of representations in three letters written by him.

The wealth of information in the texts by BIPOC authors included in nineteenth-century missionary periodicals will undoubtedly change our understanding of the people, histories, and historiographies presented. The specificities of each letter allow readers to see the particular issues, preferences, and microhistories of each. Scholars will be able to use this information to enrich and enliven studies from biblical hermeneutics to contextual theology to textual analysis of voice, including tone, timbre, style and narrative devices, in order to understand these unique expressions and their literary traditions. Scholars can “remember” BIPOC historiographies in collecting and collating these “membra,” these scattered literary parts, to build a far more accurate and complete rendition of the people who lived in these histories and contexts, whilst constantly remaining alert to the potential for manipulation.

This intervention is most exciting because it means that scholars who work with these texts may just be able to listen to these individuals speak their issues in their own voices, on their own terms.

Citation Practices in this Essay

The project team for “BIPOC Voices” encountered a variety of non-European names in the project's periodical pieces for which it proved difficult to determine what qualified as the forename and surname or if such a distinction was even appropriate for the given cultural context. The project's limited scope prevented full investigation of each case. As a result, the team decided that referencing of the project's primary texts in both in-text citations and “Works Cited” lists would use the full name of each primary text contributor – non-European and European – in the order given in the text.

The result is that all project materials consistently follow two citation practices. For periodical piece contributors, the project materials use full names in the original order for all individuals for citation purposes. For the authors of other primary and secondary texts, the project materials default to using only surnames for in-text citations and to following the convention of "surname, forename" in “Works Cited” lists. (See Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom's lesson plans on “Transimperial Networks and East Asia” for a comparable use case.)

Works Cited

Aljoe, Nicole. 2012. Creole Testimonies, Slave Narratives from the British West Indies, 1709-1838. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Aljoe, Nicole, Bryccan Carey, and Thomas W. Krise, eds. 2018. Literary Histories of the Early Anglophone Caribbean Islands in the Stream. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Anonymous, Adam Kok, and Willem Uithaalder. (1851) 2022. “The Hottentot Rebellion.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Kasey Peters, Trevor Bleick, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, Charles Pamla, and Boyce Mama. (1872) 2022. “South Africa. Graham’s Town District.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Trevor Bleick, Kasey Peters, and Kenneth C. Crowell, translated by James Dwane, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, [South African Missionary Society], Jan, and Karolus. (1804) 2022. “South African Mission.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Kasey Peters, Trevor Bleick, and Kenneth C. Crowell, translated by Anonymous ["Translated from the Dutch"], solidarity edition.

Anonymous, and Robert Moffat. 1849. “Kuruman. The Bechuana Christian in Death.” Missionary Magazine and Chronicle 13 (155): 59–60.

Balia, Daryl M. 1992. “Bridge over Troubled Waters: Charles Pamla and the Taylor Revival in South Africa.” Methodist History 30 (2): 78–90.

Bakare-Yusuf, Bibi. 2018. “Archival Fever.” In Dipsaus. Dipsaus Podcast.Bessong, Aroga, Dieudonné Prosper, and Michael Kenmogne. 2007. “Bible Translation in Africa: A Post-Missionary Approach.” In A History of Bible Translation, edited by Philip Noss, 351–85. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura.

Biko, Steve. (1978) 2004. I Write What I Like. Johannesburg: Picador Africa.

Brock, Peggy, Norman Etherington, Gareth Griffiths, and Jacqueline Van Gent, eds. 2015. Indigenous Evangelists and Questions of Authority in the British Empire 1750- 1940. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

D’Ignazio, Catherine, and Lauren F. Klein. 2020. Data Feminism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Egbunu, Emmanuel A.S. 2021. Pathfinders for Christianity in Northern Nigeria (1862-1940): Early CMS Activities at the Niger-Benue Confluence. Eugene, OR: Resource Publications.

Fuchs, Martin, Antje Linkenbacj, and Wolfgang Reinhard, eds. 2014. Individualisierung Durch Christliche Mission? Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London and New York: Verso.

Hartman, Saidiya V. 2018. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12 (2): 1–14.

Hirmer, Monika, Romina Istratii, and Iris Lim. 2018. “Editorial II: The Praxis of Decolonisation.” The SOAS Journal of Postgraduate Research, October, 10–11.

Jones, Arun W., ed. 2021. Christian Interculture: Texts and Voices from Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press.

Karabinos, Michael. 2018. “In the Shadows of the Continuum: Testing the Records Continuum Model through the Foreign and Commonwealth Office ‘Migrated Archives.’” Archival Science 18: 207–24.

Mercer, Kobena. 1990. “Black Art and the Burden of Representation” Third Text 10: 61-78.

Mercer, Kobena. 1991. “Looking for Trouble” Transition 51.

Mokae, Sabata-Mpho and Willan, Brian, eds. 2021. Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi - History, Criticism and Celebration Jacana/James Curry: Johannesburg and New York.

Samuelson, Meg. 2007. Remembering the Nation, Dismembering Women? Stories of the South African Transition Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Sandiford, K. 2018. “Memory, Rememory, and the Moral Constitution of Caribbean Literary History.” In Literary Histories of the Early Anglophone Caribbean, Islands in the Stream, edited by N. N. Aljoe, Bryaccan Cary, and Thomas W. Krise, 11–35. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schapera, Isaac. 1930. The Khoisan Peoples Of South Africa. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Wicomb, Zoë. 1998. “Shame and Identity: The Case of the Coloured in South Africa.” In Writing South Africa: Literature, Apartheid and Democracy, 1970-1995, edited by Derek Attridge and Rosemary Jolly, 91–107. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.