Overview

This essay, one of a series published by One More Voice for the “BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press” (henceforth “BIPOC Voices”) project, examines a set of the Indian (primarily Hindu) voices found in Victorian Christian missionary periodicals and seeks to determine their quality as historical sources. In taking this approach, the essay provides historical context for Christianity in India, then critically examines British missionary periodicals containing writings from Indians. In conclusion, the essay indicates that the Indian voices found in missionary periodical pieces are, ironically, better representations of British thoughts and beliefs than of Indian ones.

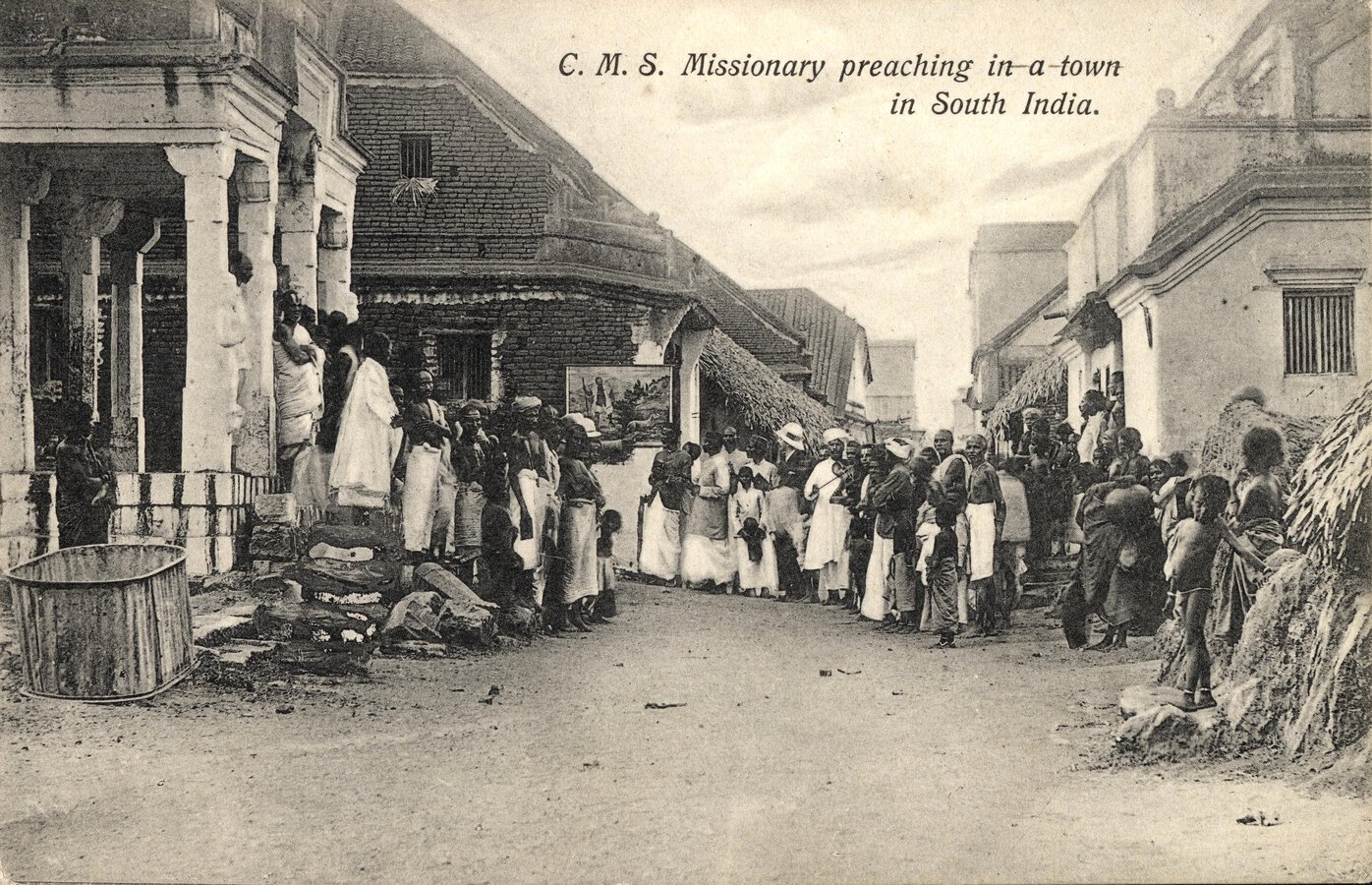

British Colonial Rule and Missionary Organizations

In the nineteenth century, the British sought to impose their form of Christianity on India. Historians divide British rule over India into two periods, the earlier period of Company rule (1757-1858) and a later one of Crown rule (1858-1947). The British government’s commitment to religious non-interference in the subcontinent provides continuity between the two periods (Copland 2006, 1031, 1045). Rather than the government, private missionary societies such as the Church Missionary Society and London Missionary Society served as the driving force spreading Anglican Christianity in India during the two periods in question (Lindenfeld 2021, 188).

Although both the Company and Crown rule colonial governments of India separated themselves from religious work, in the years between 1813 and 1857 the British East India Company did collaborate with missionary societies in advancing Christian missionary work. The high point of this partnership came during the 1830s when the collaborating powers decided that government-sponsored English education would be the way to create loyal subjects (Copland 2006, 1040).

Missionary societies contributed eagerly by establishing missionary schools as the societies saw it as another avenue to secure converts (Copland 2006, 1041). The biggest victory for missionary work came in 1831 when the British East India Company conceded to missionary political pressure and began reversing its, the Company’s, stance from upholding India’s religious status quo to passing laws that protected Indian Christian converts (1043). The Company also enacted policies in favor of the lower castes and advanced social reform bills banning local customs like sati, which undermined the existing ruling landholding class, giving them causes for resentment (Bauman 2013, 637).

The Company-missionary partnership, however, came to an abrupt end with the outbreak of the Indian Revolt in 1857. The event also marked the end of Company rule in India as Britain transferred the colony to the Crown. Both parties, i.e., the government and missionary societies gained different lessons from the revolt. The government returned to its policy of religious non-interference, while the revolt galvanized missionary societies to double their efforts (Copland 2006, 1044).

Missionary Activity and Social Tension

Missionary periodicals offer scholars a glimpse of the forms of Christianity the British sought to impose in India during this time. As private entities, missionary societies had to raise funds; an effective method for doing so involved publishing stories in missionary periodicals to elicit the public’s interest and financial contributions (Griffiths 2005, 154). Hence, articles and stories in missionary periodicals served as advertisements to the public to support ongoing patronage. Missionary societies, in effect, offered the “service” of Christian conversion and salvation.

Put differently, the societies had an incentive to show their readers success stories that fell in line with the ideals of the missionary societies, whether in the form of published biographies of recent converts or otherwise. A review of such biographies, as documented by the “BIPOC Voices” project, reveals the general themes of rejecting idolatry and pagan rituals to be common among the biographies as well as the theme of a recent convert’s Christian faith being put to a significant test.

Despite such positive representations, theological inflexibility and Christianity’s adoption by lower caste Indian society led to real-world tensions and social unrest in India. The development of these tensions reflected a change from the results of prior Christian efforts. For example, Syriac Thomas Christians could trace their roots in India as far back as the 345 CE (180), while Jesuit missionaries played an active role in India in the sixteenth century onward and, after them, the German Pietists in the eighteenth century (Lindenfeld 2021, 180, 183).

The syncretic nature of Thomas Christian faith distinguished their practice and involved heavy participation in local Hindu rites. The Jesuits were initially tolerant of local customs and religious beliefs even as the Jesuits tried to reform the Thomas Christians; these efforts became more forceful as the Jesuits became more stringent in enforcing Christianity in the Portuguese colony of Goa. Conversion of Hindu orphans, destruction of non-Christian images, and banning of religious feasts were the result, all of which ended in violence and subversion (Lindenfeld 2021 180-181). The German Pietists found themselves compelled to accommodate caste distinctions to spread the Christian faith. The accommodation went as far as to physically separate the congregation during mass (184). In relation to the Thomas Christians, British missionaries considered such syncretism unacceptable and pushed for a more orthodox type of faith along Protestant lines (Bauman 2013, 637).

Concurrently, nineteenth-century British missionary work evolved effectively among lower caste Indians because the British practice of Christianity allowed the lower castes to gain social mobility. British missionaries also adopted a position against allowing caste distinction in Christianity (Lindenfeld 2021, 187). The tempering and denial of the caste system served as an affront to all levels of Indian society. For instance, the association with Christianity led Thomas Christians to lose their high caste status and even resulted in riots in some places. As for recent Indian converts, they bore the brunt of anti-Christian violence. Action taken against them could range from social ostracization and eviction to murder (Bauman 2013, 637).

Although British missionary work proved effective with the lower castes and theologically inflexible, there’s evidence to suggest that the missionaries still participated in the caste system to spread the Christian faith. In an 1855 report from Wesleyan missionaries, an Indian bible woman (a local Christian proselytizer), Sanjivi, found herself judged for her low caste even though she received praised for her piety and devotion to the cause (Joseph 2018, 59-60). During the 1850s, there occurred a concerted push to spread the gospel to higher caste women who were usually confined in the house due to the practice of “purdah (seclusion in the part of the home known as zenana, or women’s quarters)” (Lindenfeld 2021, 199). Sanjivi’s caste status served as an obstacle to her proselytizing to higher caste women.

Missionary Manipulation of Indian Voices

Such historical developments provide an important, often invisible context for examining Indian biographies in missionary periodicals. As noted, such biographies often partake of common recurring themes. For example, one type of conversion biography features the given convert’s family acting as an obstacle for the convert attempting to maintain Christian faith; in such biographies, the convert’s steadfast faith itself guides the convert through the difficult times. The obstacles in such narratives take several forms, such as threats of ostracization, violence, or the compulsion to perform Hindu rituals.

“History of a Female Convert” (Anonymous, [J. Shrieves], and Anonymous 1849) exemplifies this type of biography. In this biography, family and neighbors threaten an anonymous convert from Cuddapah (modern day Kadapa) by indicating that she and her children will face social ostracization if she continues to “forsake their gods [i.e., the gods of the family and neighbors]” and continues to be “inclined to embrace Christianity” (9). The female convert is from the “farmer caste” and has Christian relatives and a husband who converted to Christianity after their marriage. As the narrative continues, the female convert prepares to send her children to receive Christian education with their spiritual salvation in mind, but her family and neighbors intervene to dissuade her. They do this by stressing that her children will “all become outcasts'' if she proceeds as planned (9).

Another biography (Anonymous and P. Siddhalingappa 1872), published just a few decades later, takes up similar themes, particularly in its report of a convert (Sangappa) whose father threatens to beat him if he continues to read Christian texts (98). Both this biography and the former end with the converts staying true to their beliefs, with the former anonymous protagonist successfully sending her children to receive a Christian education and the latter, Sangappa, fleeing to a Christian mission to be baptized (Anonymous, [J. Shrieves], and Anonymous, 9; Anonymous and P. Siddhalingappa 1872, 98).

The act of being forced to perform Hindu rituals represents another challenge that converts in such conversion biographies face and appears to be a more prevalent theme than ostracization. For example, the biographies discussed above also feature instances of converts being forced or tricked to apostatize. The former anonymous convert reports that her family attempted to “tempt” her into going to temples and “assume the mark of idolatry” on her head, while the latter convert, Sanggapa, describes being forced to “worship images of stones” and a deity named Jangam (Anonymous, [J. Shrieves], and Anonymous, 9; Anonymous and P. Siddhalingappa 1872, 98). These moves have a particular significance because “Hinduism is not a ‘religion of the book.’ Therefore idol worship and rituals are of crucial importance in the observance of the faith” (Ghosh 2022).

In some periodical pieces, the threat level rises. In “Trials of Converts in India” (Anonymous and Jagadishwar Bhattachargya [1853] 2022), for example, the mother of the convert Shrinath becomes hysterical at her son’s conversion to Christianity and “scheme[s]” with friends and relatives to “take away Shrinath from [the Christian mission compound]” (106-07). The piece continues with Shrinath “fall[ing] into her snare” and being kidnapped and put under house arrest by his mother with the assumed goal of forcing him, Shrinath, to abandon Christianity (107). Yet the biography concludes with Shrinath still firm in his faith despite the trials. Collectively, such narratives suggest that British missionaries viewed idolatry and apostasy as huge issues among their Indian congregation. By publishing the stories of those who resisted those Hindu practices in favor of Christianity, the missionary societies demonstrated their success to audiences at home in Britain.

In looking at these examples, scholars might find it useful to apply a gendered lens to the reading of the passages, although space prevents a full such reading here. However, it's worth noting that in these passages scholars “can observe that the man is engaged in reading Christian texts which might have motivated him to convert. The woman might have had more practical considerations for conversion” (Ghosh 2022). Such differences, historically, also emerge on a wider scale. For example, Bauman (2008, 83) notes that “[o]ne of the reasons that becoming Christian generally entailed long-term economic improvement was that converts and their children received education and vocational training from the mission.” Moreover, Bauman adds that “[t]his training was particularly significant for Christian women, who as trained teachers and nurses were able to secure better-paying jobs than their Satnami counterparts.”

Missionary periodical conversion biographies thus played a key role in a larger, self-sustaining cycle. In this cycle, British missionary-led conversions led to violence, which, in turn, resulted in Indian narratives of faith centered on overcoming adversity, which narratives – in published form – generated domestic British zeal and interest in supporting ongoing missionary work. Yet this summary omits one key dimension of this dynamic – the fact that British missionaries oftentimes appropriated indigenous voices in missionary periodicals for their, the British missionaries’, own agendas.

Several factors resulted in such doctoring of indigenous voices. As noted, missionary periodicals provided a key way for missionary societies to secure funding. Therefore, missionary societies had a vested interest in publishing success stories to secure continued financial contributions. The societies published such success stories by retaining strict editorial control over the contents the missionaries published (Griffiths 2005, 154). The missionaries realized this control through several stages involved in the publication process.

British missionaries who claimed to have faithfully translated a given convert’s narrative applied the first layer of editing. British missionary society editors and others who edited or otherwise prepared narratives for publication added a second layer (Griffiths 2005, 153). Both groups as well as indigenous missionaries might also have strategically altered certain narratives perceived to be too scandalous or risqué for Victorian Britain. For example, it appears that missionaries had to train Panya, an East African girl rescued from slavery, to “tell the truth” when developing her missionary periodical narrative (163), a directed approach that may have centered on veiling the fact that she might had been a victim of sexual assault.

Ultimately, it would be a tremendous boon to future scholarship if we could know where exactly missionaries tampered with original sources, but this proves hard to determine without access to the original sources and/or in the absence of specific markers in the text. However, the “BIPOC Voices” project concludes that such tampering did occur, even though explicit textual markers for such tampering are not present, and it is impossible to determine the full scale of such tampering.

Conclusion

Missionary periodicals subjected Indian voices in the periodicals to censorship and doctoring to show progress in the evangelical mission. Recurrent themes found in missionary periodicals, such as those that this essay has taken up, provide strong indicators of such editorial meddling. Without attention to these themes, readers may be tempted to take the Indian voices in the periodicals as the representation of authentic Indian thoughts and beliefs. It is precisely this default tendency that allowed missionaries to camouflage their own thoughts behind the veneer of Indian voices.

British missionaries in India were fixated on spreading “orthodox” Christianity to the Indian masses. Historical records indicate that this agenda caused strife at all levels of Indian society. British missionaries may or may not have been aware of the tensions that they were building, but if they were, the periodical texts taken up by this essay clearly work to spin these tensions as “tests” for new converts. In this context, missionary periodicals thus published the results of those who “passed the test” as biographies and other types of narratives. Through this process, missionary periodicals effectively erased the agency of Indian Christian converts.

However, it is worth noting that such agency was everywhere present, as one concluding example can show. “Not Far from the Kingdom of God” (Anonymous, [Vaughan], and Anonymous [1875] 2022), a missionary periodical piece published in the latter part of the nineteenth century, records the complaints of missionaries about Indians who claim to believe in the Bible but refused to accept Jesus for various reasons. These include the loss of social status, employment, and family as results – temporal things about which a good Christian should not worry (13). Although the passage in question is brief, it offers one example, potentially, of many instances in periodicals that come close to recording something like the “true” voices of Indian people by documenting the ways in which those people resisted the evangelizing efforts of British missionaries.

Citation Practices in this Essay

The project team for “BIPOC Voices” encountered a variety of non-European names in the project's periodical pieces for which it proved difficult to determine what qualified as the forename and surname or if such a distinction was even appropriate for the given cultural context. The project's limited scope prevented full investigation of each case. As a result, the team decided that referencing of the project's primary texts in both in-text citations and “Works Cited” lists would use the full name of each primary text contributor – non-European and European – in the order given in the text.

The result is that all project materials consistently follow two citation practices. For periodical piece contributors, the project materials use full names in the original order for all individuals for citation purposes. For the authors of other primary and secondary texts, the project materials default to using only surnames for in-text citations and to following the convention of "surname, forename" in “Works Cited” lists. (See Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom's lesson plans on “Transimperial Networks and East Asia” for a comparable use case.)

Works Cited

Anonymous, [J. Shrieves], and Anonymous. 1849. “History of a Female Convert.” Missionary Magazine and Chronicle 13 (152): 8–9.

Anonymous, and Jagadishwar Bhattachargya. (1853) 2022. “Trials of Converts in India.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Cassie Fletcher, Jocelyn Spoor, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, and P. Siddhalingappa. 1872. “Appendix III - South India Eastern and Western Missions (2) Reports from the Missionaries.” The Seventy-Eighth Report of the London Missionary Society 13: 98.

Anonymous, [Vaughan], and Anonymous. (1875) 2022. “‘Not Far From the Kingdom of God.’” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Cassie Fletcher and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Bauman, Chad M. 2008. Christian Identity and Dalit Religion in Hindu India, 1868-1947. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. D. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Bauman, Chad M. 2013. “Hindu-Christian Conflict in India: Globalization, Conversion, and the Coterminal Castes and Tribes.” The Journal of Asian Studies 72 (3): 633–53.

Copland, Ian. 2006. “Christianity as an Arm of Empire: The Ambiguous Case of India under the Company, C. 1813-1858.” The Historical Journal 49 (4): 1025–54.

Ghosh, Sutanuka. 2022. “Peer-Review Feedback: ‘Manipulating Indian Voices in Nineteenth-Century Missionary Periodicals.’” Document.

Griffiths, Gareth. 2005. “‘Trained to Tell the Truth’: Missionaries, Converts, and Narration.” In Missions and Empire, edited by Norman Etherington, 153–72. Oxford University Press.

Joseph, Deepti Myriam. 2018. “Negotiating Race and Gender in Mission Work.” Unpublished Manuscript.

Lindenfeld, David. 2021. World Christianity and Indigenous Experience: A Global History, 1500–2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.