- Overview

- Studying Victorian Colonial Missions

- The Victorian Christian Mindset

- Publishing and Earning Money

- Missionary Education of Indigenous People

- The Evangelized: Finding a New Family

- The Evangelizer: Casual Conversation, Critical Topic

- Conclusion

- A Note on Citation Practices

- Works Cited

- Page Citation

- Lead Image Details

Overview

This essay analyzes a selection of texts published in the Victorian periodical press by indigenous peoples. These pieces appeared in the Church Missionary Society (CMS) periodical Church Missionary Gleaner during the mid- to late-1800s and comprise part of a set of several hundred relevant pieces identified by One More Voice for the “BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press” (henceforth “BIPOC Voices”) project.

After outlining key elements of missionary studies as well as presenting background information about the Victorian mission mindset, this paper selects and analyzes three texts from the missionary periodical press – each from a different mission field (i.e., geographical location where missionaries work; in this case, China, India, and Sierra Leone) – to discuss indigenous representation of missionary education as well as the potential implications and impacts of these representations on a British Victorian audience.

This essay argues that the missionary periodical press, including publications such as the Church Missionary Gleaner, represented evangelized indigenous peoples to British Victorian audiences as needing missionary intervention to civilize their (the indigenous peoples’) seemingly wayward lives. Such depictions financially fueled missionary endeavors. This essay explores a selection of three pieces from the Church Missionary Gleaner as a way of foregrounding how this monetary agenda might have influenced silent editorial changes to the texts of the original indigenous authors.

Studying Victorian Colonial Missions

The prevalence of antiracist and decolonial work in the current academic environment has encouraged scholars to (re)discover long-hidden texts in archives, books, and elsewhere. Such work often involves researching texts that have representations of or contributions from indigenous peoples.

“Indigenous,” the term itself, is difficult to define. K. Tsianina Lomawaima (2016, 150) states that the term references peoples with shared “experiences that are rooted in places, landscapes, seas, and movements of ancient time-depth; that have been and are being substantially shaped by the ongoing structures of settler colonialism; and that express unfolding contemporary dynamism.” Georgina Stewart (2018, 740) agrees with this place-based notion, but adds that “[t]he word ‘indigenous’ refers to the notion of a place-based human ethnic culture that has not migrated from its homeland, and is not a settler or colonial population.” Rosemary Hennessy (2004, 29-31) complicates this by explaining how being “indigenous” in a more contemporary sense is a threefold label: a reference to a specific group of people in a particular land; a term that signals social, historical, and natural connection to a locale; and a word that signifies a form of political resistance to “capitalist exploitation” while “honor[ing] the natural and human resources on which social life depends.”

Homeland and experience in and on that land throughout multiple generations and centuries thus ground Lomawaima and Stewart’s observations about the concept of indigenous. Hennessy’s explanation of “indigenous” similarly situates the term with land, but also adds an element of resistance to “capitalist exploitation” of the land and its resources (which might be broadened to include European colonialism and colonial missionary movements), thus foregrounding the agency of indigenous peoples.

The term “indigenous,” therefore, describes peoples around the world who know “colonisation was and is literal” and “is a reality and is not in the past” (Lewis 2016, 192). The term also means much more than “something similar to the older word ‘native’” (Stewart 2018, 740), which nineteenth-century texts – including those taken up by the “BIPOC Voices” project – default to using to describe relevant individuals and groups in an undifferentiated way and in a way that suggests both a lack of “civilization” and cultural, political, technological and other types of ossification.

In using the term “indigenous,” consequently, this essay responds to and seeks to redress such historical injustices. In doing so, the essay builds from the premise that the peoples described in the primary texts are not one people group confined to one geographical area, but rather reflects the notion that “indigenous” peoples are a variety of people from across the globe – each with their own cultures, beliefs, and practices, and each with increasing resistance to or questioning of the exploitation of their way of life. Thus, by using the term “indigenous,” this essay allows for cultural and societal fluctuation and differentiation amongst peoples from varying locations and ethnic groups.

The above conceptual grounding and the following analysis of the representation of indigenous peoples in relation to colonial Christian missionary work places the work of the present essay in in a wider critical context. Scholars in archival indigenous research initially ignored or avoided colonial Christian missionary studies because these scholars “understood missionary activity as an iconoclastic assault on indigenous cultures” where missionaries forced indigenous peoples to convert “not through choice but as a technique for survival” (Wild-Wood 2021, 93). However, other scholars have come to identify missions as a type of “cultural exchange” where both missionary and convert change and a “new form of Christianity” is “embedded in a new situation” (Wild-Wood 2021, 93). This “new situation” refers to two distinct cultures connecting and melding cultures and/or cultural perspectives.

Regardless of the stance, scholars now welcome archival colonial missions scholarship because they recognize the impact missions work has had upon the world, as well as how the archived voices in missionary literature can present previously unknown or unconsidered “insights into the relationships between religion and politics” and “editors and reading communities” (Jensz and Acke 2013, 368). These insights give scholars the opportunity to make new connections between historical objects as scholars recover more about the Victorian colonial worldview from the perspective of indigenous peoples.

The Victorian Christian Mindset

For globally-distributed peoples living in the Victorian period, Christianity and colonization often occurred simultaneously, especially as thousands of missionaries, supported by mission societies, conflated being Christian and civilized. Isaac Yue (2009, 1) states that “[t]he sense of being a Christian represents a fundamentally important ideal to the conceptualization of Victorian cultural identity in that it not only dictated to society an imaginary concept of identity after which the Victorian civilization tried to pattern itself, but also led to the manifestation of cultural ideologies such as the ambiguously defined Victorian virtue and work ethic.” In a sense, Christianity, morality, duty, and British Victorian culture merged, and the Victorians came to believe that other cultures needed to be “civilised” to attain this level of morality (even though this moral identity was more mythical than factual) (3).

However, some missionary societies recognized the error and complications with this methodology and shifted strategies, including the CMS. Since the primary texts in this essay are from CMS publications, the CMS’s unique history and strategy shift are important for contextualizing these primary texts. The CMS founders were members of the Clapham Sect, which was a group of social reformers who were members in the Church of England (Allpress 2014). The CMS maintained “their roots in the Anglican Communion” and, although “the earliest missionaries were actually German Lutherans” (Church Mission Society 2016), the CMS missionaries during the publications of the primary texts in this essay were likely members of the Anglican Church.

In the early 1840s, CMS Secretary Henry Venn attempted to change the CMS’s motivations from “convert-and-civilise” to a strategy centered on prioritizing “native agency,” which “promoted the growth of national churches administered from within by native pastors, native lay leadership and, eventually, a native episcopate.” Integrating “local cultural traditions” and “Christian truths” indicates this strategy valued non-Western cultures (Turner 2015, 198). Missionaries had to learn the language/vernacular, customs, and habits of the people with whom they worked (Turner 2015, 199; Ballantyne 2018, 123-24; Edmonds 2007, 201).

However, the CMS membership did not scrupulously follow or universally apply “the idea of ‘Christianity without civilisation,’” and “the convert-and-civilise approach was still widely practiced in the field, irrespective of official intent” (Turner 2015, 199). Discrepancies in deployment caused a nonuniform approach to missionary efforts around the world. This irregular application of CMS practices hints at how, once in the field, missionaries often independently decided how to evangelize. Their reports home to the CMS may or may not detail the full extent of their abiding or not abiding by CMS approaches, so scholars should bear this in mind when working with these materials.

Publishing and Earning Money

Societies like the CMS needed outside income to continue their work. As a result, they sought to convey missionary feats to a wider audience via publications as part of a larger strategy to secure monetary backing for future missionary trips. The CMS had many such publications, especially during the Victorian era. These often were iterations of the society’s name with terms such as “Gleaner,” “Intelligencer,” “Outlook,” or “Review” added to the end (Cason 1981, 285). Each publication had a different purpose and audience, including “children, women, or converts in the field” (Jensz and Acke 2013, 371). Of importance to the present essay is the Church Missionary Gleaner, a monthly publication that ran from 1841 to 1921, excluding the years from 1869 to 1874 (Cason 1981, 285).

Publications such as Church Missionary Gleaner provided audiences with what the editors thought would paint the CMS in a good light and encourage its financial support. This included censoring and editing information “to manipulate readerships as well as to comply with political norms” (Jensz and Acke 2013, 372). The many relevant pieces from missionary periodicals identified through One More Voice’s “BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press” project indicate that such editorial work could often include mediating and/or strategically revising the original text of missionaries and indigenous peoples.

For example, certain recurring sections of the Church Missionary Gleaner, such as “Gleanings from Recent Letters,” only publish – as the title suggests – selections or “gleanings” from letters and journals sent to CMS, not the full texts. Along similar lines, in individual pieces, such as “The Outcast from China Brought Safely Home” (Anonymous and John Dennis Blonde [1851] 2022) and others, CMS editors insert bracketed words to reorient the author’s text, as seen in the following example: “How shall I meet the heathen in the day of judgement, when they cry with a loud voice against me, that I lived on earth when they did, and that I got to know the way to heaven, and yet I went not [nor sent] to tell them!” (Anonymous and John Dennis Blonde [1851] 2022). Overall, it is unclear how much editorial intervention and rewriting occurred through this type of selection and mediation, although it is clear that it often occurred to some lesser or greater degree.

In general, the unedited letters, journals, and narratives used to create the content of missionary periodicals can be difficult to find and access, if such material even survives. Thus, scholars must rely on the published versions and must carefully scrutinize Victorian editorial reassurances about a given individual’s original words in order to consider the potential degree of editorial tampering, as in the following examples, each of which makes claims for indigenous authorship and/or context while sometimes overtly insinuating editorial intervention: “[...] chiefly in Dennis’s own words” (Anonymous and John Dennis Blonde [1851] 2022); “[...] was written a few months ago by one of the Native Christian teachers” (Anonymous, [John Cain], and A.S. [1874] 2022); and “is given by Yonan [...] in a letter addressed to his friends” (Anonymous and Yonan [1852] 2022). Although potentially mediated, such pieces nonetheless often represent the only option for engaging with Victorian-era indigenous perspectives on the missionary enterprise.

Missionary Education of Indigenous People

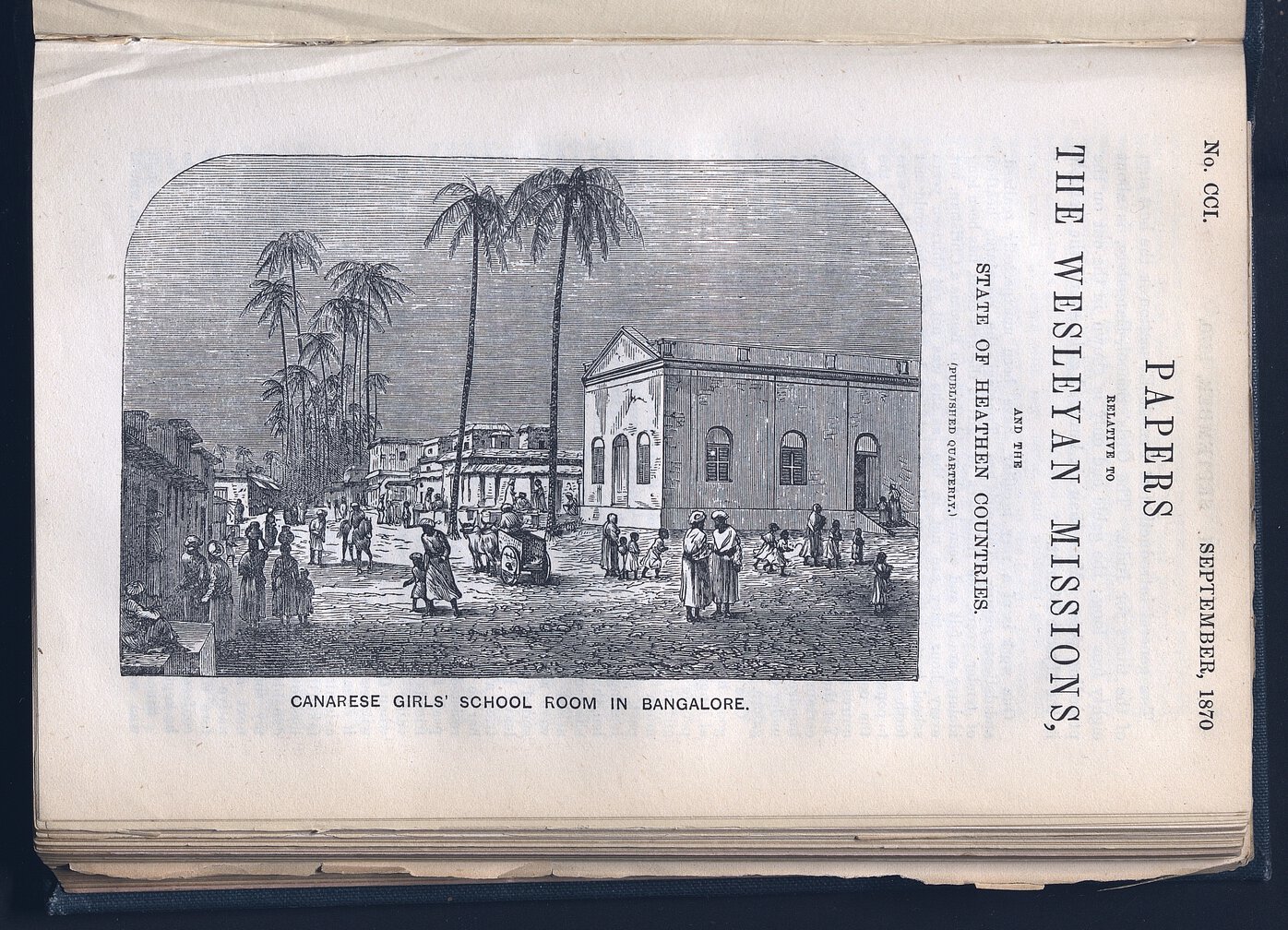

Missionaries usually presented Christian doctrine to indigenous peoples through a form of education that they, the missionaries, created. This education often occurred in local schools, a site that enabled missionaries to monitor and implement a curriculum. However, these schools had to be locally accepted to operate. For instance, even though many groups in India were not Christians, the local education department allowed mission schools because they viewed them as “neutral,” “religious,” and “hence neither agnostic nor Godless” (Bellenoit 2007, 371).

The government‘s approval did not mean the local groups accepted the schools. For example, some mission schools in India “had to go to extraordinary lengths to convince locals that conversion was not [their] primary objective.” Families would only send students to schools aiming to educate, not convert (Bellenoit 2007, 373).

Missionary education often taught English and other British customs, though some missionaries used local vernacular when they deemed indigenous peoples’ customs important, including early New Zealand missions where missionaries tried to accommodate “tapu,” or Māori sacred things (Ballantyne 2018, 123-24).

Regardless of the challenges in the mission field such as convincing locals, learning languages, and so forth, missionaries provided evidence of their work to their sponsoring societies which would, in turn, declare “successes” to their wider western audience via periodicals like Church Missionary Gleaner. In these publications, the representation of indigenous voices sometimes took the form of texts from indigenous missionaries themselves and sometimes from the evangelized indigenous peoples. Felicity Jensz and Hanna Acke (2013, 368) state that according to the CMS’s Reverend Thomas Green, “missionary periodicals provided a means of ‘influencing’ the minds of readers in order to excite the missionary spirit among the home community.”

Thus, the representation of indigenous voices in Church Missionary Gleaner – in terms of both missionaries and those being evangelized – seeks to influence the primarily western “home community” readership by introducing two types of indigenous peoples: those who need to hear and accept the Gospel and those who teach it. In other words, those who attempt to reject Christian doctrine and those who seemingly accept it without hesitation. Both perspectives “encourage home audiences to support [missionary] endeavor[s] both financially and morally” by “proving” that the goal of mission work is being accomplished, even when pitted against seemingly unwilling peoples, societies, and otherwise non-Western cultures (Jensz and Acke 2013, 371).

But the Church Missionary Gleaner offers more than just these two presentations of indigenous peoples. As missionary-prompted education occurs, the periodical also demonstrates to its readership how missions function, i.e., what it takes to convert, civilize, or otherwise westernize peoples who did not previously believe in the Christian God, and the hardships and setbacks that occur in the mission field in terms of this agenda. This suggests to the Victorian audience that missionary endeavors are difficult and require much external and internal support and investment to function and prosper.

The following closer analysis of three texts brings out examples of how indigenous voices in the role of the evangelizer and the evangelized operated in missionary fields as well as the potential impacts of such voices on the British Victorian audience reading these texts via the Victorian periodical press. (Note: Although all the texts are written in the first-person, this essay will discuss the works as if they were in the third-person authorship as a means of acknowledging the potential British mediation.)

The Evangelized: Finding a New Family

When looking at the representation of indigenous peoples in missionary schools far from home, two indigenous-authored texts from the missionary periodical press present similar ideas about evangelized students: “The Outcast from China Brought Safely Home” (Anonymous and John Dennis Blonde [1851] 2022; henceforth “The Outcast”) and “A Hindu’s Narrative of His Own Conversion” (Anonymous, [John Cain], and A.S. [1874] 2022; henceforth “A Hindu’s Narrative”).

Both texts introduce pupils who study at distant mission schools, which limit or completely restrict their ability to stay connected to their seemingly abusive or harsh biological families. Such representations promote the idea that to learn Christian doctrine and become civilized, one must divide potential converts and their seemingly problematic families. Although this disruption of the family unit may at first seem cruel to the audience, reconciliation occurs when the youths find a new (and properly moral) Christian “family.”

“The Outcast” by John Dennis Blonde is an autobiography about a Chinese boy who finds safety among English soldiers after running from abusive home life. He goes to England with the soldiers and converts to Christianity while attending school but dies before returning to China as a missionary. “A Hindu’s Narrative” by an Indian mission school teacher whose initials are given as “A.S.” recounts the author’s conversion from Hinduism to Christianity despite familial objections. His conversion occurs after attending and boarding at a mission school a few towns from his home.

Both texts draw the audience into the narrative by quickly scoping the childhoods of each character: ones that involve abusive and/or neglectful fathers and, as a result, unhappy children. For example, Blonde at one point believes his father wants to drown him, but Blonde refuses to follow the latter “up wrong street” where he (Blonde) would be thrown “into deep river from high wall” (Anonymous and John Dennis Blonde [1851] 2022). Although A.S. does not confront such extreme situations, he does say his adoptive father (that is, his maternal aunt’s husband) “treated [him] severely at times,” causing him to love his adoptive family “very little” (Anonymous, [John Cain], and A.S. [1874] 2022).

The fact that the periodical pieces begin with these pathos-filled scenes suggests that the pieces function as “a form of propaganda” (Jensz and Acke 2013, 371) and that, like many advertisements, the pieces seek to play on the emotions of the audience. In this case, the agenda is to convince the readership that these youths are in unloving households and that these earthly fathers (of these two children and, implicitly, those of other indigenous children) have poor morals which do not align with Christ’s teachings. This produces pity in the audience as they see “the so-called heathens [...] suffering and in deep need of help” (Jensz and Acke 2013, 372), particularly from missionaries who can provide education about the heavenly Father.

The apparently unloving families of both Blonde and A.S. motivate them to leave home. Upon departing, the two individuals find solace by forming familial-like relationships with Christian or otherwise western (and thus “civilized”) people. Being receptive to Christian relationships presents these indigenous youths in more of a sympathetic light to Victorian audiences because Blonde and the author are represented as not entirely against Christianity and thus are more easily converted.

Blonde’s new family is with English soldiers whom he is “glad to remain with” and even travel with to England (Anonymous and John Dennis Blonde [1851] 2022). Although the soldiers are not described as Christian, they are western and the fact that Blonde feels safer with them than with his own family insinuates that the soldiers at least have a Victorian sense of morality, duty, and virtue.

A.S. finds a new family at his mission school. He sees the headmaster Mr. Noble “more as a parent than as a master” because Mr. Noble treats the author “most affectionately in every way” (Anonymous, [John Cain], and A.S. [1874] 2022). In this light, Mr. Noble seems to be a better earthly father than the author’s adoptive father because Mr. Noble presents more of a “normative Christian, and generally European [notion] of ‘civilization’” (Jensz and Acke 2013, 373) by being kind.

Having close Christian and western relationships also causes both boys to investigate Christianity, a faith to which their biological parents and likely most of their other relations did not adhere. The exploration and, as it emerges, eventual acceptance of Christianity proves to the Victorian audience that missionary work is successful, even if the triumph comes from disrupting original familial ties and forming new Christian ones. In fact, the texts suggest that holding fast to familial ties might impede the missionary efforts of cultivating morality.

The concept of families complicating the conversion process was fully felt in India where “mission schools could never be as spiritual as they wished” because Indian families wanted “humanistic and ethical education and not the religious type missionaries propagated” (Bellenoit 2007, 372). For instance, Edward Oakley, the headmaster of Ramsay College in the late 1800s, “confided that even though he prayed for conversion, he admitted that they would ‘empty our classrooms’” (372-73). There were also many other examples of emptied Indian schools due to conversions, including ones near Lucknow, Azamgarh, and Allahabad (373). The quick removal of students after a conversion is likely a sign that Indian families, despite their seeming appreciation of the logic of Western education, did not want their children to fully assimilate to missionary-promoted Christianity.

The texts thus suggest that family impedance is a true issue for missionary conversion of indigenous children. This might be why Blonde’s education occurs at “Mr. Beardshall’s academy at Ashcroft” where the “Christian instruction received by him … was blessed to his conversion” (Anonymous and John Dennis Blonde [1851] 2022). Thus, the audience sees that his Christian relationships help him to have a “proper” life that includes a western education and values.

A.S. is not presented with as straightforward an approach whereby the youth goes to school and is seemingly immediately converted. A.S., instead, initially neglects the Bible and faces being “degraded” to a “class below.” So, he diligently reads “the Bible, but simply to gain [Mr. Noble’s] good-will” (Anonymous, [John Cain], and A.S. [1874] 2022). That is, he studies the Bible to appease his new father-figure.

However, although reading the Bible begins as a means to an end, A.S. eventually converts to Christianity after many months and perhaps years, despite his family’s resistance (Anonymous, [John Cain], and A.S. [1874] 2022). Converting to Christianity and learning English through such missionary education eventually enables A.S. to hold a job teaching in a Christian missionary school like the one he attended. Thus, conversion enables a form of upward mobility, and he earns a kind of financial stability that the rest of his family and/or peers might have lacked.

Comparing the representations of these conversions is important. Blonde’s conversion occurs in the span of a sentence that does not discuss his potential issues with or unacceptance of Christianity. He simply converts based on the instruction he receives. This presents missionary work as especially easy when the child is completely isolated from his family.

In comparison to this seemingly simple conversion, the representation of the anonymous author’s conversion suggests that the conversion might have been more difficult because the author’s family was nearby. Indeed, the author still visited them on school vacations, and they had a direct influence on his life.

Although these two narratives are only a few of the many published in the missionary periodical press and presented as “authored” by indigenous individuals, the evidence of these two narratives suggests that completely separating children from their parents enables them to no longer feel the tension and complications between their old life and their new one. Such separation also potentially suggests to the Victorian audience that a child’s conversion hinges on their becoming completely dependent on missionaries. Thus, the narratives collectively suggest that missionaries require more support from Victorian audiences to secure lodging, food, education, and eventually conversion of these children.

The Evangelizer: Casual Conversation, Critical Topic

However, missionary periodicals also indicate that Christian education of indigenous peoples need not occur in the formal settings presented in mission schools to be worthy of investment by Victorian audiences. Nathaniel M. Bull in “The ‘Gleaner’ in the Timneh Country” (Anonymous and Nathaniel M. Bull [1874] 2022) shows that education can occur in seemingly casual conversations while visiting local indigenous populations. This conversation with local adults shows the Victorian audience that missionary work is just as important for current generations (adults) as it is for future generations (children). The informal approach also reveals to Victorian audiences that evangelizing is more than teaching youths and that a more comprehensive approach is needed, one that involves battling seemingly misinformed adults who do not have a proper understanding of the Christian God.

This short text set in the vicinity of Sierra Leone presents indigenous catechist Bull as he briefly explains a conversation about salvation and entering heaven with two local Mende men. During this conversation, Bull says, “no one has a right to heaven,” a place without sin, because “no man on earth” “sinneth not” (Anonymous and Nathaniel M. Bull [1874] 2022).

In response to Bull’s statement, the two men engage in an instance of Wild-Wood’s idea of a “cultural exchange” because their interpretation of salvation and entering heaven differs from Bull’s theology. One of the visitors describes his concept of salvation as follows: “All living men are committing sin (and God weighs the sins and righteousness of all men), and should your sins which you have committed surpass the good, if you die on the morrow, you will go to hell; but should the good outweigh the evil, and you die on the morrow, you will be taken by God to heaven” (Anonymous and Nathaniel M. Bull [1874] 2022). This visitor believes that one’s earthly works either take one to heaven or hell, depending on the works’ morality, i.e., if one works hard enough and does enough good, then the Christian God deems one can enter heaven.

Bull’s Victorian audience would have recognized that this concept of salvation – coming from more than just a personal relationship with Jesus Christ – was a heresy that the Church battled since its formation, as noted in the Book of Acts (e.g., 17:16-34) where newly converted Christians (who were once Jews) tried to teach Gentiles that everyone still had to conform to the Law. The Apostles corrected these new Christians' error. As such, the readership would likely have believed that these two men, like the newly converted Christians in Acts, needed a re-education in biblical theology.

After this, Bull makes an aside to his audience and asserts that one man’s heretical belief verifies that all Mende men believe this heresy: “This, sir, is the ground upon which all the Mende men stand to go to heaven” (Anonymous and Nathaniel M. Bull [1874] 2022). Now, Bull leads the audience to consider that not only do the missionaries need to reeducate these two individual men but that all the Mende men need missionaries to help them recognize biblical theology unaffected by the heretical influences of other religions.

Jensz and Acke (2013, 372) state that missionary periodical readers were often “personally addressed” and “were constructed as potent agents holding the destiny of millions of so-called heathens in their hands.” Thus, Bull’s aside addressing the reader as “sir” also pulls the audience further into the narrative by giving them a calling: to support missions work and save these “heathen” peoples from their heretical beliefs.

But Bull does not end the article with this heresy unresolved. To combat it and thus show how missionaries fight this “widespread” issue, Bull validates CMS publications by using a parable from the May 1874 issue of the CMS Gleaner (Anonymous and Nathaniel M. Bull [1874] 2022). This validation of the publication in which Bull’s article appears (in fact, from another issue from the same year) aligns with the idea that “internal consistency [...] minimized dissent [...] through the citation of other periodicals and the reprinting of articles from other mission fields (Jensz and Acke 2013, 372). By citing another CMS article, Bull not only encourages readers to go back and read the article in question but also pulls the two mission fields together as a unified force against heresy, despite their geographical and temporal separation.

The parable Bull references originated in India (Anonymous 1874, 50), and therefore Bull invokes the CMS concept of “native agency” to fit it to his two visitors. He recognizes that the men will not understand “the local [Indian] words Baboo, rupees, fakeer” (Anonymous and Nathaniel M. Bull [1874] 2022) and thus customizes these words to fit the correct culture. Bull finds his parable opens the door for him to “propose the way of salvation by Jesus Christ alone” (Anonymous and Nathaniel M. Bull [1874] 2022), and thus addresses the heresy. By altering the language and cultural customs of a parable, Bull teaches people who might otherwise disregard his ideas.

Instances such as this one suggest to the audience that missionaries can convince indigenous peoples to change their religious views if they use the same techniques regardless of specific mission fields. Bull (and the editors) have accordingly accomplished their job: to present a story that attempts to persuade a Victorian audience to support missionary work in “heathen” areas which have inaccurate views of Christian doctrine and would be lost without such missionary work.

The informal mission work with adults combined with the formal missionary education of youths discussed earlier in the prior section of this essay works to suggest to the Victorian audience that the efforts of missionaries involve a much greater burden than conversations with possible converts. The missionaries must set up environments that cause indigenous peoples to feel invited.

Formal boarding schools give children physical and spiritual nourishment and safety, while social environments provide indigenous adults sites to discuss theology in an open, welcoming format. These environments, however, do not appear overnight, and so the periodical representations – in words that appear to come from indigenous individuals themselves – suggest to Victorian readers the immense financial and spiritual efforts needed to construct evangelical opportunities.

Conclusion

The Victorian missionary era involved many moving parts, even when only considering the periodicals produced by mission societies like the CMS. Victorian readers who believed in the importance of missions invested in such endeavors, particularly after learning about missionary work through periodicals. However, such societal support was not enough. Publications needed to do more than report to the homefront; they needed to prove successful engagement with indigenous peoples to increase support.

The representations of the three indigenous authors discussed in this paper depict them as engaging with missionary education in different ways. Two of the texts use distant missionary education to limit family contact with students while altering their purportedly immoral behavior by converting them to Christianity. The other text depicts the reeducation of adults nearby their homeland to correct seemingly rampant heresy amongst professing indigenous Christians.

Collectively, the pieces convey a set of larger points by harmonizing with their British Victorian audience’s core beliefs of morality, civilization, and virtue, and so underscore both the worthiness of missionary endeavors in the field and the need to continue supporting such endeavors.

Other Church Missionary Gleaner pieces reflect this harmonization as well. These types of works present indigenous voices as aided by their new faith in Christ. Some pieces discuss indigenous peoples’ profession of Christ on their deathbeds and their reassurance that they “have no fear of death at all” because they “depend on Christ” (Anonymous et al. [1875] 2022). Others juxtapose non-Christian ethnic groups who appear to act in a bloodthirsty manner with Christian indigenous peoples who poise themselves amongst these “heathens,” praying and trusting in the Christian God “to save [them] from [their] cruel foes” (Anonymous and Anonymous [1851] 2022). Pieces such as these reassure Victorian audiences that converting indigenous peoples makes them civilized and thus moral.

Overall, many Church Missionary Gleaner articles represent evangelized indigenous peoples as converting to Christianity and/or gaining a better understanding of Christian doctrine after a missionary intervenes in their purportedly wayward lives. These representations suggest that the support of CMS missionaries will continue to civilize these peoples who otherwise would never gain a sense of perfect Victorian cultural identity.

Thus, periodical texts, like those in this essay, ultimately serve such objectives, regardless of the evangelized indigenous people’s apparent happy and content demeanors. In fact, this appearance of happiness emerges as a facade, especially because reading these texts with a historical lens provides greater scholarly insight into the reasoning behind this perceived contentment: seemingly happy converts prove to its Victorian audience that missionary endeavors are successful, which, in turn, financially fuels more missionary work. Current scholars should take into consideration this financially-driven agenda as they attempt to analyze these texts, more so because careful reading of the texts suggests that they were edited, mediated, or otherwise altered by silent Victorian British editors.

Citation Practices in this Essay

The project team for “BIPOC Voices” encountered a variety of non-European names in the project's periodical pieces for which it proved difficult to determine what qualified as the forename and surname or if such a distinction was even appropriate for the given cultural context. The project's limited scope prevented full investigation of each case. As a result, the team decided that referencing of the project's primary texts in both in-text citations and “Works Cited” lists would use the full name of each primary text contributor – non-European and European – in the order given in the text.

The result is that all project materials consistently follow two citation practices. For periodical piece contributors, the project materials use full names in the original order for all individuals for citation purposes. For the authors of other primary and secondary texts, the project materials default to using only surnames for in-text citations and to following the convention of "surname, forename" in “Works Cited” lists. (See Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom's lesson plans on “Transimperial Networks and East Asia” for a comparable use case.)

Works Cited

Allpress, Roshan. 2014. “Setting the Scene: The Creation and Inspiration of the Church Missionary Society.” In Our Story: Aotearoa, edited by Sophia Sinclair. Christchurch, New Zealand: New Zealand Church Missionary Society.

Anonymous. 1874. “The Rev. C. B. Leupolt, Of Benares.” The Church Missionary Gleaner 1 (May): 50–51.

Anonymous, and Anonymous. (1851) 2022. “The Amazons.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Cassie Fletcher, Jocelyn Spoor, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, [John Cain], and A.S. (1874) 2022. “A Hindu’s Narrative of His Own Conversion.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Cassie Fletcher and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, and John Dennis Blonde. (1851) 2022. “The Outcast from China Brought Safely Home.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Cassie Fletcher, Jocelyn Spoor, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, and Nathaniel M. Bull. (1874) 2022. “The ‘Gleaner’ in the Timneh Country.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Cassie Fletcher and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, Samuel Johnson, Samuel Cole, T.B. Wright, Samuel Pearce, and D. Williams. (1875) 2022. “Sick and Dying Christians in Yoruba.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Cassie Fletcher and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition..

Anonymous, and Yonan. (1852) 2022. “Adult Sunday-Schools Among the Nestorians.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Cassie Fletcher, Jocelyn Spoor, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Ballantyne, Tony. 2018. “Entangled Mobilities: Missions, Māori and the Reshaping of Te Ao Hurihuri.” In Indigenous Mobilities: Across and Beyond the Antipodes, edited by Rachel Standfield, 115–44. Australian National University Press.

Bellenoit, Hayden J. A. 2007. “Missionary Education, Religion and Knowledge in India, c.1880-1915.” Modern Asian Studies 41 (2): 369–94.

Cason, Maidel. 1981. “A Survey of African Material in the Libraries and Archives of Protestant Missionary Societies in England.” History in Africa 8: 277–307.

Church Mission Society. 2016. “Our Story.” Church Mission Society. 2016. Date for section and main site given as 2016-2022.

Edmonds, Angelique. 2007. “Sedentary Topography: The Impact of the Christian Mission Society’s ‘Civilising’ Agenda on the Spatial Structure of Life in the Roper Region of Northern Australia.” In Transgressions: Critical Australian Indigenous Histories, edited by Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah, 16:193–210. Australian National University Press.

Hennessy, Rosemary. 2004. “‘Indigenize’ as Concept and Practice: A Post-NAFTA North-South Mexico Example.” English Studies in Canada 30 (3): 29–38.

Jensz, Felicity, and Hanna Acke. 2013. “The Form and Function of Nineteenth-Century Missionary Periodicals: Introduction.” Church History 82 (2): 368–73.

Lewis, Patrick. 2016. “Indigenous Methodologies as a Way of Social Transformation: What Does It Mean to Be an Ally?” International Review of Qualitative Research 9 (2): 192–94.

Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. 2016. “Indigenous Studies.” American Quarterly 68 (1): 149–60.

Stewart, Georgina. 2018. “What Does ‘Indigenous’ Mean, For Me?” Educational Philosophy and Theory 50 (8): 740–43.

Turner, Emily. 2015. “The Church Missionary Society and Architecture in the Mission Field: Evangelical Anglican Perspectives on Church Building Abroad, c.1850–1900.” Architectural History 58: 197–228.

Wild-Wood, Emma. 2021. “The Interpretations, Problems and Possibilities of Missionary Sources in the History of Christianity in Africa.” In World Christianity: Methodological Considerations, edited by Martha Frederiks and Dorottya Nagy, 92–112. Leiden: Brill.

Yue, Isaac. 2009. “Missionaries (Mis-)Representing China: Orientalism, Religion, and the Conceptualization of Victorian Cultural Identity.” Victorian Literature and Culture 37 (1): 1–10.