Overview

This essay analyzes a selection of texts published in the Victorian periodical press by racialized peoples. These pieces primarily appeared in periodicals published by the London Missionary Society (LMS) or the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (WMMS) during the 1800s and comprise part of a set of several hundred relevant pieces identified by One More Voice for the “BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press” (henceforth “BIPOC Voices”) project.

The following analysis argues that the periodicals used names and descriptions to represent racialized authors as having varying levels of “authority,” i.e., credibility and knowledge, and corresponding degrees of “civilization.” The more racialized people behaved, spoke, wrote, and appeared like British Victorians, the more the periodicals depicted the authors as meeting the levels of civilization and Christianity that British Victorians expected. This presentation of racialized converts as nearly British, i.e., almost fitting an ideal Victorian cultural identity, plays to the idea that racialized converts disowned their own heritage and culture to conform to British desires. Such representations of converts from foreign lands demonstrated missionary success to Victorian British audiences and underscored the importance of continuing such evangelical work.

Introduction

As discussed in my other essay published through the “BIPOC Voices” project (Spoor 2022), European peoples in the Victorian period, especially the British, often had a sense of a cultural identity that conflated being Christian with being civilized. This means that they believed, to some extent, that an individual could only be a Christian if that individual was “civilized,” i.e., exhibited tastes and behavioral characteristics perceived as typically Christian in British and/or European culture more generally.

Such beliefs, therefore, bled into missions work when the British went into other parts of the world. Evangelizing became entwined with promoting a moral-cultural identity grounded in British societal and religious practices such as regularly reading the Bible or wearing European-style clothing.

Colonial missionary periodicals, which document evangelization efforts, thus represent racialized authors in ways that take up the question of their level of “civility” and ability to be Christian. In particular, the use of recurring name and description details helps portray the racialized authors as being more Christian and civilized, and so these details work to heighten each racialized author’s authority.

Differences Among Naming Practices

Historically, names are important in many societies. Not only do names acknowledge specific individuals, but names also often have some sort of greater significance, whether that be historical due to passage down through generations, referential due to cultural allusions, or even religious. According to Bhaskar Kumar Kakati (2022, 423-24), “individuals have deep feelings towards their names which influence their personal adjustments and attitude towards self.” A name can reveal the “societal status [of individuals]” (424) as well as “affect the treatment that they receive in legal, educational, political, psychiatric, social, emotional, and other settings in their personal life” (426).

Li et al. (2018) find that eastern and western cultures potentially have cross-cultural differences regarding naming practice. For example, the authors indicate that, in understanding and explaining names, “American adults [of European heritage] are more likely to respond like causal theorists, whereas Chinese adults give more responses consistent with the descriptive theory” (110). The causal-historical view of naming “contends that a name refers to a person because it was linked to her in the initial act of naming and this link is then passed down through a community of speakers.” Western names are thus often “rigid”: “they continue to refer to the entity initially given the name, even when that individual turns out to have none of the properties we associate with that name” (108). The descriptive view of naming, maintained by more eastern cultures, “holds that a name gets its referent through definite descriptions. When competent speakers use a name, they refer to whoever uniquely satisfies the description associated with that name” (108).

So, although generalizations about the east and west can only go so far and should always be made cautiously because of the potential for lapsing into Orientalist discourse (see Said 1978 and the voluminous scholarship that has followed in that work's wake), research such as that cited suggests that western cultures tend to link an individual with a name – regardless of new information or changed descriptions associated with that name – because the individual was originally given the name. Eastern cultures, conversely, might view personal names as variable and so open to change when the associated descriptions no longer adquately account for the given individual or even when there is a reason to bring in a new set of descriptions. For example, prior to India’s independence from Great Britain, upper-caste Tamil Nadu-speaking Hindu men gave themselves caste names to denote their authority and prestige over lower-caste men (which included those practicing non-Hindu religions). As such, a lower caste member who practiced a non-Hindu religion might add a higher caste name to their given name to gain more power, even though they did not actually belong to said caste (Britto 1986, 358).

Kakati and Liu et al.’s scholarship also gives insight into the importance of names in colonial-era missionary periodicals. For instance, some of the Victorian periodical texts under discussion in this essay use racialized author names that obviously originate in western Judeo-Christian culture, whereas other texts use author names that originate in non-western cultures. The difference in these names had the potential, in the nineteenth century, to impact how readers perceived the authority of the racialized authors, but might also – beyond any missionary periodical editorial tampering – have reflected the idea that racialized authors who converted to Christianity viewed their inward spiritual change as necessitating an outward name change because, to return to the point above, the descriptions associated with that individual had changed.

Names in Primary Texts

This issue of names and potential name changing arises in a number of missionary periodical texts by racialized authors. For example, James Solomon is the name given to the author of “Abakrampa, Extract of a Letter from the Rev. James A. Solomon, Native Minister, Dated Abakrampa, November 8th, 1872” (James A. Solomon 1873). The first and last parts of this name, “James” and “Solomon,” have biblical resonance. James is an “English, Biblical” name that “was the name of two apostles in the New Testament” (Campbell 2020a), while Solomon is a “Biblical, English, Jewish, Biblical Latin, [and] Biblical Greek” name that is not “overly common in the Christian world,” but was the name of the third king of Israel “[a]s told in the Old Testament” (Campbell 2020b).

Although not all relevant periodical racialized authors have two biblical names, many have at least a biblical forename, for example Philip ([John] Philip, Edward Edwards, and Anonymous [1823] 2022), Adam (Anonymous, Adam Kok, and Willem Uithaalder [1851] 2022), Jacob (Anonymous and Jacob Walker [1874] 2022), Thomas (Thomas J. Marshall 1873), and Joseph (Joseph May 1874). Others have distinctly anglicized names such as Robert (Anonymous and Robert N. Mashaba [1904] 2022), Charles, and Boyce (Anonymous, Charles Pamla, and Boyce Mama [1872] 2022).

Although the periodical texts available to the “BIPOC Voices” project do not make clear when or why these authors received these names (at birth, after baptism, by silent editors, etc.), Sarah Abel, George Tyson, and Gisli Palsson’s (2019) discussion of African people enslaved in the Americas in the 1700s can provide insight into racialized peoples’ name changes during this general time period. In particular, the authors discuss how “the adoption of European and Christian names can be read as efforts toward resistance and self-determination on the part of the enslaved, and how these appropriations can be squared against colonial authorities’ attempts to preserve racial distinctions” (335).

Although the racialized authors discussed here were not enslaved people (or at least do not appear to be so based on the available textual evidence), the change to a biblical or anglicized name served in a similar fashion, as the choice caused racial distinctions to blur. This blurring would thus have given the racialized authors more authority in the eyes of Victorian readers when it came to evangelizing because both types of names (biblical and anglicized) carried authority in Victorian-era British culture.

However, not all racialized authors in the missionary periodical pieces taken up by the “BIPOC Voices” project have biblical or anglicized names. The names of racialized authors such as Ranavalmanjaka and Rainilaiarivory appear to be original. The use of these original names, therefore, may be due to the fact that the names signify authority. Ranavalomanjaka is the “Sovereign of Madagascar,” while Rainilaiarivony is the “Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief in Madagascar,” as signed in their 1875 published text “Royal Proclamation on Slavery” (Anonymous, Ranavolmanjaka, and Rainilaiarivony [1875] 2022). Their names would have been well known in the cultural and political context of Madagascar. Thus, with such renowned names (and the political status which these names signified), these authors would not have needed additional authority from adopting anglicized or biblical names.

However, the periodical pieces taken up by our project also include one example of an author with both types of names. In the text “The Autobiography of Poonapun, a Heathen, Baptized on February 17, 1850, By the Name of Nathaniel” (Anonymous, Poonapun, and Authautchee [1850] 2022), the published names of the author are both Poonapun and Nathaniel. In this case, the title of the piece helps explain this seeming anomaly as well as provide insight into why some authors likely have biblical or anglicized names – namely, that the authors assumed such names at the moment of baptism. However, although the “BIPOC Voices” project does not include other examples of authors with both types of names, further research into this name change and the author’s Tamil cultural context helps clarify the broader context for this specific use of a dual name.

In discussing Tamil culture, Francis Britto (1986), an Indian linguist recognized for his work on Tamil culture, indicates that “[t]he Tamils follow some of the most uncommon practices associated with personal names [...] Many Tamils moving in international circles are also likely to have one name in their birth certificate, another in their school record, and still another in their visa or business documents.” Britto goes on to state that “[t]he structure of a Tamil personal name is significantly different from that of an American or European one” (349). Such observations coupled with Li et al.’s research (see above) potentially help to illuminate Poonapun’s nineteenth-century situation and the reasons for his willingness to accept a Biblical anglicized name.

In light of such research, it is possible that Poonapun, the individual represented as authoring the missionary periodical piece in question, might have chosen to use or might have had others assign this name strategically – as a way of gaining authority with British audiences. Likewise, the name change might reflect the historical individual’s belief that baptism necessitated a name change because the facts supporting the name Poonapun (i.e., childhood, religion, sinful nature, etc.) changed when he converted. Thus, his new name reflects this change and reassures missionaries (and the Victorian British audience) that he has truly "chang[ed] religious identity" (Liebau 2003, 81).

In summary, whether a racialized author has a biblical and/or anglicized name, a racialized name, or a mixture of both, in the context of the missionary periodicals under discussion here, the author gains some sort of heightened authority because the name symbolizes more than just their individuality. It shows the silent work of missionary periodical editors in attempting to try to give this individual more authority, the given author’s willingness to become more civilized, the author’s ability to conform to Victorian-era British Christian values, or the author’s personal authority based on their political position.

When reading works by these authors, it is important to ponder the significance of the name provided in the publication. In a rhetorical sense, thinking about this small part of a text foregrounds important questions about the maneuvers, decisions, and arguments the editor and/or author makes in the piece. In a more general sense, the names of these racialized authors do more than just label the individuals in question – the names give cultural, sociological, and ideological insight into each author or, at minimum, into the strategic goals of representing the author.

Descriptions of Racialized Authors

Although names are important, the descriptions given of racialized authors in the titles and bodies of periodical texts prove even more revealing in terms of the descriptions’ seeming levels of authority and British civility. Some descriptions reflect the given author’s perceived ethnic culture or identity. Others use discriminatory and/or derogatory language determined by the appearance or personal history of the given author. However, in all cases, despite any surface-level denigration, the descriptions likewise work to elevate the author’s authority by linking them with often non-racialized people or activities and thus presenting the authors as more British (and therefore more Christian) than the authors’ own culture and heritage would indicate.

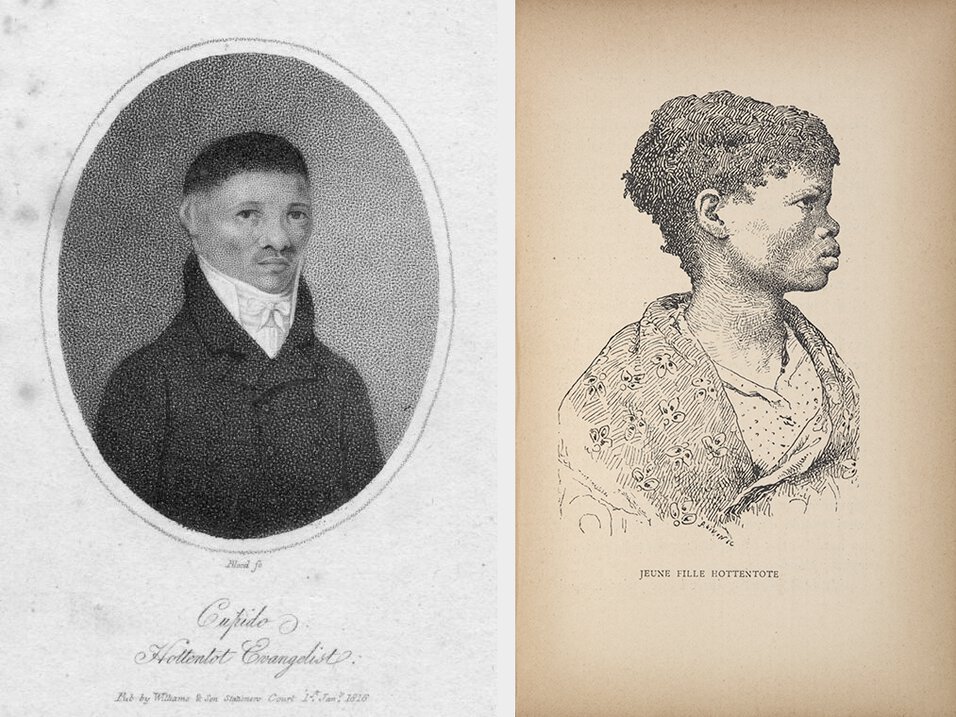

For instance, in “Africa. Character of Africaner,” John Philip describes a racialized man “whose conversion and subsequent conduct display one of the most striking instances of the power of renewing grace” ([John] Philip, Edward Edwards, and Anonymous [1823] 2022). Besides using many Christian buzzwords (“humility,” “diligence,” “undissembled piety,” etc.) to describe Africaner’s morality and dedication to the Christian God, Philip also says he “was upon the whole a very superior Hottentot,” because “[h]is mind had been much improved by his intercourse with missionaries” ([John] Philip, Edward Edwards, and Anonymous [1823] 2022). Philip thus elevates Africaner relationally because of his, Africaner’s, willingness to interact with missionaries and conform to their ways of life.

Along similar lines, the periodical texts describe two other authors, Jan and Karolus, as “Bastard Hottentot” (Anonymous et al. [1802] 2022). In separate letters, each author uses this phrase in their signature, and the periodicals also use this phrase in the subtitles of the pieces (i.e., “Letter of a Bastard Hottentot” and “Letter of Another Bastard Hottentot”). This causes the authors to be self-described and editorially labeled by the phrase “Bastard Hottentot,” a representation method that suggests a sort of double denigration. However, despite this demeaning wording, the overall representation of the authors works to heighten their authority, as explained below. (Note: It is possible that the use of “bastard” in this context refers to the Baster ethnic group, but the text provides insufficient evidence to make this determination; as a result, the present essay defaults to understanding the term “bastard” by its more common definition of being “born out of wedlock.”)

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first recording of the term “Hottentot” occurred in the late seventeenth century, in the context of white Europeans applying it to the Khoekhoe (aka Khoikhoi) peoples. Although the OED indicates that the application of Hottentot to African peoples, especially those of South African heritage, became rather common by the nineteenth century (“Hottentot, n. and Adj.,” n.d.), use of the term also gained in its derogatory resonance and reinforced stereotypes such as the idea “that Hottentots have no minds and are not capable of improvement, and therefore cannot and ought not to be put upon a level with other nations, as it respects intellect” ([John] Philip, Edward Edwards, and Anonymous [1823] 2022).

In showing Africaner to be a “very superior Hottentot,” Philip thus suggests that Africaner took on better (i.e., “very superior”) characteristics because of missionary influence, not because of his, Africaner’s, own abilities. Thus, Africaner, in the logic of periodical publication, can only surmount geography and ethnic identity to become “very superior” by becoming more pious than other non-Christian racialized southern African peoples.

Similarly, the periodical texts represent Jan and Karolus as overcoming the weight of more sin than other southern African racialized individuals due to the fact that the two men were born out of wedlock. Jan and Karolus overcame this sin because they fell “in love with that dear Jesus” (Anonymous et al. [1802] 2022) and became Christians, which insinuates that only being Christian enabled them to conquer this sin. Although the representations of Jan and Karolus may not characterize the men as extremely pious like Africaner, the representations still indicate that the former two men still feel that their “sins are more than the hairs of [their heads]” (Anonymous et al. [1802] 2022), i.e., that they recognize many of their words, thoughts, and actions do not align with the Christian God’s demands. The two men are thus elevated above other southern African peoples, the periodicals suggest, because the two men recognize their own sinful natures and their need for missionaries to teach them “the doctrine of Jesus” (Anonymous et al. [1802] 2022).

All three of these authors (Africaner, Jan, Karolus) would have, therefore, gained more authority in the minds of Victorian readers because of these Christian values, which, in turn, distinguished the men from other members of their original communities. Yet, concurrently, missionary periodical discourse demeans these men by applying derogatory names and descriptions. This insinuates that despite these authors’ attempts to grow in Victorian civility, faith, and thus authority, their representation in missionary periodicals prohibits them from truly ever reaching British standing; they will always be some form of outcast despite trying to mimic and conform to British ideals (cf. Bhabha 1984).

As a result, in contrast to the seemingly futile goal of mimicking British cultural values, descriptions of racialized authors in missionary texts bring authority to these individuals by proving that their values align with Victorian Christian values, even though the men come from different cultures than that of the intended audience of the periodicals. As such, the descriptions, like the names, give the authors more authority by making claims for the authors’ elevated levels of civility.

Conclusion

In missionary periodicals, racialized authority derives from a vast array of interlocking components, including authors’ names and descriptions. This authority often comes at the cost of the racialized authors leaving their own heritages and cultures behind and attempting to cleave to British customs, as suggested by the periodical pieces.

For readers and scholars, it is important to emphasize that this authority, as in the examples cited in this essay, often comes from peripheral material, not necessarily from the representation of the given author’s knowledge about any particular topic.

For Victorian readers, a western name, or other material attempting to imitate Victorian British Christian culture (i.e., Bible quoting, portrait poses, etc.) would have, potentially, served as a way for the racialized authors (and/or for the silent missionary periodical editors on behalf of the racialized authors) to gain authority with readers. Sounding, looking, and being British – even if just superficially – had the potential to lead British audiences to put more credibility in the words of these authors. As such, the racialized authors or the periodical editors (who would have final say in the publication and thus be able to change any and/or all words in the original article) might phrase their text(s) to gain such credibility and thus become more authoritative with British Victorian audiences. This, in turn, would sell more publications and thus further support missionary efforts.

By recognizing these subtle dynamics when considering the work of racialized authors in missionary periodical literature, scholars can open new avenues of scholarship centered on the elements that endowed these authors with what Victorian readers would have seen as “authority” and “civilization.”

Citation Practices in this Essay

The project team for “BIPOC Voices” encountered a variety of non-European names in the project's periodical pieces for which it proved difficult to determine what qualified as the forename and surname or if such a distinction was even appropriate for the given cultural context. The project's limited scope prevented full investigation of each case. As a result, the team decided that referencing of the project's primary texts in both in-text citations and “Works Cited” lists would use the full name of each primary text contributor – non-European and European – in the order given in the text.

The result is that all project materials consistently follow two citation practices. For periodical piece contributors, the project materials use full names in the original order for all individuals for citation purposes. For the authors of other primary and secondary texts, the project materials default to using only surnames for in-text citations and to following the convention of "surname, forename" in “Works Cited” lists. (See Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom's lesson plans on “Transimperial Networks and East Asia” for a comparable use case.)

Works Cited

Abel, Sarah, George F. Tyson, and Gisli Palsson. 2019. “From Enslavement to Emancipation: Naming Practices in the Danish West Indies.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 61 (2): 332–65.

Anonymous, Adam Kok, and Willem Uithaalder. (1851) 2022. “The Hottentot Rebellion.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Kasey Peters, Trevor Bleick, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, Charles Pamla, and Boyce Mama. (1872) 2022. “South Africa. Graham’s Town District.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Trevor Bleick, Kasey Peters, and Kenneth C. Crowell, translated by James Dwane, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, and Jacob Walker. (1874) 2022. “Jamaica—The Native Pastorate.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Kasey Peters, Trevor Bleick, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, Poonapun, and Authautchee. (1850) 2022. “The Autobiography of Poonapun [...]; Autobiography of Authautchee [...].” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Trevor Bleick, Kasey Peters, and Kenneth C. Crowell, translated by J. Shrieves, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, Ranavolmanjaka, and Rainilaiarivony. (1875) 2022. “Rearrangements of the Madagascar Mission.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Trevor Bleick, Kasey Peters, and Kenneth C. Crowell, translated by Anonymous, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, and Robert N. Mashaba. (1904) 2022. “A Letter from Robert Mashaba.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Kasey Peters, Trevor Bleick, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, [South African Missionary Society], Jan, and Karolus. (1802) 2022. “South African Mission.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Kasey Peters, Trevor Bleick, and Kenneth C. Crowell, translated by Anonymous ["Translated from the Dutch"], solidarity edition.

Bhabha, Homi. 1984. “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse.” October 28: 125–33.

Britto, Francis. 1986. “Personal Names in Tamil Society.” Anthropological Linguistics 28 (3): 349–65.

Campbell, Mike. 2020a. “Meaning, Origin and History of the Name James.” Behind the Name. May 29, 2020.

Campbell, Mike. 2020b. “Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Solomon.” Behind the Name. May 29, 2020.

“Hottentot, n. and Adj.” n.d. In OED: Oxford English Dictionary; The Definitive Record of the English Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

James A. Solomon. 1873. “Abakrampa, Extract of a Letter from the Rev. James A. Solomon, Native Minister, Dated Abakrampa, November 8th, 1872.” The Wesleyan Missionary Notices 5, Fourth Series (48): 12–13.

[John] Philip, Edward Edwards, and Anonymous. (1823) 2022. “Africa. Character of Africaner.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Trevor Bleick, Kasey Peters, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Joseph May. 1874. “West Africa. Sierra Leone District. Extract of a Letter from Rev. Joseph May, Freetown, November 8th, 1873.” The Wesleyan Missionary Notices 6, Fourth Series (February): 48–49.

Kakati, Bhaskar Kumar. 2022. “What Is in a Name? The Politics of Name Changing.” Sociological Bulletin 71 (3): 421–36.

Li, Jincai, Longgen Liu, Elizabeth Chalmers, and Jesse Snedeker. 2018. “What Is in a Name?” Cognition 171 (February): 108–11.

Liebau, Heike. “Country Priests, Catechists, Schoolsmasters, and the Tranquebar Mission.” In Christians and Missionaries in India: Cross-Cultural Communication Since 1500, edited by Robert Eric Frykenberg, 70–92. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2003.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Spoor, Jocelyn. 2022. “Representing Indigenous Perspectives on Missionary Education in Victorian Periodicals.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, peer reviewed by Shantanu Majee and Adrian S. Wisnicki, solidarity edition.

Thomas J. Marshall. 1873. “West Africa. Letter from the Rev. Thomas J. Marshall, Native Missionary, Dated Abbeokuta, May 26th, 1873.” The Wesleyan Missionary Notices 5, Fourth Series (September): 209–10.