Overview

This essay takes up the stylized language of missionary periodicals and examines the question of how African peoples are represented in these periodicals. The analyzed texts appeared in the early- to mid- nineteenth century in the Missionary Chronicle, The Chronicle of the London Missionary Society, and The Wesleyan Missionary Notices and make up a small selection of a much larger body of work compiled by One More Voice for the “BIPOC Voices from the Victorian Periodical Press” project (henceforth “BIPOC Voices”).

Missionary periodicals have provided a rich historical resource for scholars with interests in both missionary practices and western expansion writ large. A legacy of scholars, largely influenced by the works of Jean and John Comaroff, have investigated Christian missionary texts and the potentials and problems of using these texts to understand BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) voices, particularly in Africa. The Comaroffs’ multi-volume Of Revelation and Revolution (1991; 1997) provides an in-depth analysis of missionary interactions in southern Africa during a period of significant intercultural exchange. The Comaroffs’ work, in turn, influenced a range of scholars who came to explore the historical, social, and cultural nuances of missionary work across the globe.

This essay builds on and is inspired by such scholarship. More specifically, the essay extends the work of Elizabeth Elbourne (2002), who explores how biblical texts influenced and enabled a tense relationship between the Khoekhoe peoples, British empire, and the London Missionary Society (LMS); and Winter Jade Werner (2018), who examines the ideological tensions between Christian missionaries, non-western converts (largely in India), and the burgeoning social scientists who were emerging in Europe during the nineteenth century. The essay also responds to the work of Emma Wild-Wood (2021), who offers a detailed overview of the complicated history of missionary periodical scholarship and outlines how these archival texts were often biased by the concerns of missionaries and their supporters.

These scholars provide key cultural and historical contexts that help to reimagine missionary work as a multidimensional pursuit which had immense ramifications for non-western peoples and cultures. This essay develops its analysis through a close look at stylized language as published in a selection of missionary periodicals and seeks to contextualize this language by examining inconsistencies found within periodical representations of both written and spoken versions of the language.

The essay shows how missionary periodicals are unique objects that purport to incorporate both European and BIPOC voices within the same publication. However, while the missionary periodicals provide a key resource for scholarship that engages with a broad range of voices, an analysis of the actual texts published in Protestant missionary periodicals shows little variation between European and BIPOC language.

This highly stylized language suggests that there was heavy mediation by the editors of the periodicals such that little survives of “original” BIPOC voices in the periodical texts. As a result, this essay echoes and deepens some of the overarching arguments of the “BIPOC Voices” project as a whole by using detailed linguistic analysis to suggest that scholars must proceed with caution when using these periodical pieces as sources for BIPOC perspectives and, moreover, that any notion of “recovery” must be highly qualified.

As this essay and the “BIPOC Voices” project more generally argue, white British missionaries, editors, and others heavily mediated periodical texts featuring BIPOC creators, a point that illustrates the repressive practices that shaped the development of many missionary periodical pieces. Despite such overall mediation, this essay suggests that spoken language gains new significance in shaping the interactions between British missionaries and African peoples.

While the overall language presented in relevant missionary periodical texts often includes elements that devalue African peoples, such as quantifiable conversion data, missionaries regularly turn to anecdotes that incorporate the spoken language in order to praise key characteristics of African peoples (oftentimes of multilingual African missionaries). This binary underscores that the language of periodical texts featuring BIPOC creators could at once work in two ways: as a tool for the suppression of African individuality and as a means of laying the basis for intercultural respect.

Background

The rise of systematized knowledge is a key feature of Europe’s growth, and it had sweeping effects on the ways western society communicated with itself. For instance, Henry Louis Gates (1985, 8) recognizes this trend and comments on its impacts on Black people in his landmark introduction to Critical Inquiry:

The urge toward the systematization of all human knowledge (by which we characterize the Enlightenment) led directly to the relegation of black people to a lower place in the great chain of being, an ancient construct that arranged all of creation on a vertical scale from plants, insects, and animals through man to the angels and God himself.

With Gates’ claims in mind, it is eminently important to recognize the ways in which both written and spoken language in periodical texts was used to represent engagements between Europeans and African peoples. This essay takes up this task as it relates to linguistic trends in Protestant missionary periodical texts and the way African peoples were represented to the broad periodical readership through these trends.

The language of letters and other kinds of periodical pieces featuring BIPOC individuals were often among the only non-fiction examples of European and African intercultural engagement to which the European public had access. As a result, missionary periodicals offered their audience the promise of serving a genuine, intercultural educational purpose in the way they represented various African cultures and peoples through language. Despite this, many installments in the missionary periodical genre predeominantly served an institutional purpose.

The primary goal of missionary periodicals was to acquire financial support and prove the efficacy of Christian missions to a European audience (Petzke 2018, Wild-Wood 2021). Through an analysis of the discourse as it is presented in Protestant missionary periodicals, we can see how the organizational requirements of missionary literature and the presence of often unnamed editors might have influenced BIPOC authorship in a way that deemphasized non-Christian perspectives. Such deemphasis took advantage of the lack of public familiarity with BIPOC perspectives to advance representations that promoted Christian ideology and that served the agenda of securing public financial support for British missionary endeavors.

Linguistic Emphasis in Christian Missions

Language, both written and spoken, served as a key medium of interaction between missionaries and African peoples and/or BIPOC groups around the globe. As Sandra Nickel (2015, 120) states, “Language may be one of the most powerful tools human beings have at their disposal to position themselves in relation to others and define their view of themselves.” In the nineteenth century, in the context of intercultural interactions between the British and others, language served at least two distinct purposes: spoken language was the means through which European missionaries and African peoples expressed themselves and engaged in intercultural dialogue, and, in the context of missionary periodicals, printed language served as a primary way to represent African peoples.

The role of missionaries was, first and foremost, to spread the word of God and convert the “heathen population” (Petzke 2018, 185) to Christianity; the proliferation of education (informed by westernized standards of civility) was a secondary goal. Promoting literacy and establishing written versions of non-European languages were ancillary endeavors that characterized missionary engagement.

Spreading Christianity was certainly the central motivation, but many Christians believed that each person should be able to read the Bible in their own language. Schools and vernacular newspapers, which helped to teach locals to read and write, were established alongside churches in many of the places missionaries were established (Volz 2020). This insistence that African peoples adopt written versions of their language underscores the importance of writing as a means of documentation and knowledge acquisition. It may also point to a devaluation of orality.

A perceived rhetorical inequality was an early point of tension in the interactions between missionaries and African peoples. Stephen Volz (2020) mentions as an example John Brown, a European missionary and the first editor of Mahoko (a Tswana newspaper) who became openly critical of African contributions. Brown claimed that “‘Tswana have not yet learned how to write words that can be published for people to read in the newspaper,’ and ‘we would like all the words of our newspaper to say something, or even to teach something, but we cannot do anything with many of the letters that we handle except to destroy them’” (600). Both Brown and his editorial successor, Roger Price, argued that the writings of Tswana contributors were “too personal, informal or poorly written for the public forum of the newspaper” (600). Despite the novelty of a written form of the Tswana language, there was a clear dissonance in what was deemed “valuable” to these European editors, which resulted in a censoring of African voices.

Written and spoken language was not solely used as an exclusionary tool, however; the embrace of African languages, knowledge, and cultural practices – often by African preachers – helped Christian missionaries reach a broad audience and build trust amongst many communities. An anonymous narrator recalls the effect Diphukwe, a converted African preacher, had on a group of attendees:

The astonished people listened with curiosity and wondering amazement. It was not only the new and wonderful words spoken by a white man in their courtyard and in their own tongue that day that astonished them, but that a black man, one who, though not of the same tribe, was one of the same language, that he also should have the selfsame news to tell, while he told it in his own words – it was this that made it such a wonderful thing to their ears. As you can imagine, much curious comment was put forth, but the prevailing feeling was one of amazement. “We expected,” said they, “to hear about white people and white people’s customs; and you spoke to us about our own customs and about ourselves, strange words such as we had never dreamed hearing” (Anonymous and Diphukwe [1878] 2022)

This exchange shows the excitement brought by linguistic and cultural familiarity and an embrace of intercultural exchange. The representation of this exchange is a stark contrast to the comments of Brown and Price, who instead criticized the rhetorical skills of the Tswana people and used those skills as a means to exclude their voices and experiences.

Representation as Data

If we are to recognize the emphasis missionaries placed on the use of written language in their own imagining of the “civilized” person, then it feels necessary to turn a critical eye to the way that such language was used and represented within Protestant missionary periodical texts. Despite the depictions of African peoples only just beginning to to grasp the English language in interpersonal interactions, the words many missionary periodicals ascribed to the African individuals would seem to reflect a different reality.

The language presented as coming from African contributors in the missionary periodicals, particularly its written version in the form of letters and other such documents, appears nearly indistinguishable – grammatically and otherwise – from that of the European missionaries; the language shows no signs of coming from individuals who had only recently learned English. This suggests the influence of invisible editors who participated in an erasure of the African voices that may not fit within the expectations or requirements of the missions.

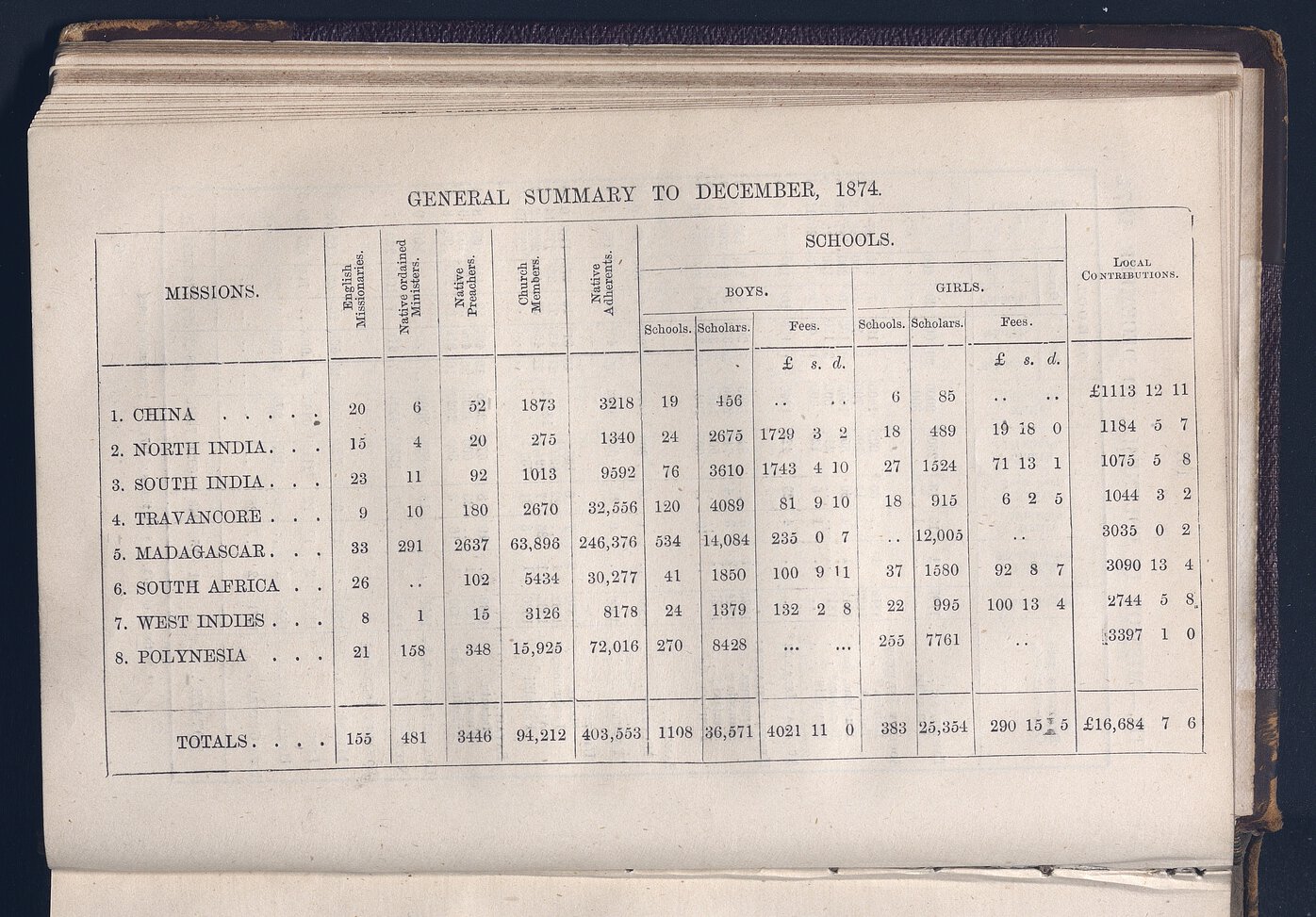

Moreover, the language that comprises much of the relevant periodical texts centers on what might be called “quantifiable conversion data,” i.e., computational data that centers on African conversion to Christianity. Such conversion data placed the business side of Christianity at the forefront of missionary publications. The goal of relevant African-authored pieces in Protestant missionary periodicals, then, seems to be advertising missionary successes within African cultures rather than attempting to convey the peoples or their customs to British readers who might not be familiar with such cultures.

Specifically, much of the language printed in the extracts of letters chosen by the unnamed editors of these missionary periodicals reads like a recordkeeper’s journal in which the data of African converts (plus finances associated with conversion) are central themes. For instance, such stylized language emerges in letter extracts from Rev. J.M. Dwane (1877) and Rev. James Lewana (1872), respectively, that appeared in The Wesleyan Missionary Notices:

We give glory to God for the wonderful way in which He has prospered this Church both spiritually and financially. We have one hundred and twenty members in full, and fifty-nine on trial, fifteen Leaders and ten Local Preachers. In these numbers I do not include those converted lately since the end of December. Our services are very largely attended. On Sundays many people are obliged to go away for want of room in our chapel. Class-meetings are regularly attended, and threepence a week, and two shillings or two shillings and sixpence a quarter, given by each member. They will not be confined to one penny a week, and one shilling a quarter. (J.M. Dwane [1877] 2022)

* * *

Since you left me in charge of this Circuit I have seen the mighty power of God in calling sinners to repentance, and to Himself. Both in Graham’s Town and Spring Vale, and at Assagai Bush, many have been converted from their heathenism, and have joined the classes; at Assagai Bush fifty are joined to the Society, and at Spring Vale, a new place, ten have been publicly baptized, and eleven are on trial, and here in Graham’s Town our members have increased, and our subscriptions also. (Anonymous, [W.J. Davis], and James Lewana [1872] 2022)

Despite both Dwane and Lewana being African ministers, their language – or at least the way it is represented in the periodical texts – offers little to distinguish them as such. As a later extract in this essay shows, the printed language attributed to Dwane is particularly critical in his representation of other African peoples. In addition, the use of conversion data by both authors as it relates to individuals, donations, and subscriptions takes a similar form which, in each case, foregrounds the success of missionary conversion efforts.

Any use of cultural information, as it appears in these extracts and others of a similar nature, seems to be qualified or overshadowed by associated references to conversion data. In the following two examples drawn from the texts of, respectively, Rev. Boyce Mama (1872), another African missionary, who cites quantifiable conversion data related to multiple towns to show his success in the region; and Rev. Evan Evans (1822), a British missionary, who combines demographic data and referenced the number of potential converts in making a request for a larger chapel:

When I first came here the number of members was less than it is now. There were sixteen members at Tamara, and forty-seven on trial: now there are forty-eight members and forty-seven on trial. At Equgqwala there were ten members, and now there are thirty-six. There were five classes, and now there are thirteen classes. Total, eighty-four members, and good many on trial. (Anonymous, Charles Pamla, and Boyce Mama [1872] 2022)

* * *

The number of hearers in the village and vicinity amounts on average to about 1100 whites and 1200 blacks; in fact there are few now to be found who have not attended several times.[...]

There are, it appears, about 5000 heathen in the Paarl and its vicinity. There are 175 slaves and free blacks on the school list; but, as many of them are obliged to come only in turn, the attendance in general is from 40 to 80. (Evan Evans 1822, 119)

The letters from Mama and Evans, like those of Dwane and Lewana, emphasize missionary success and conversion numbers at the cost of elaboration on, for example, any cultural, social, or political features related to the towns mentioned.

While the above citations are all extracts, and it’s not possible to know the full contents of the letters from these extracts, such examples suggest editorial interventions that lead to the representation of African peoples as data points and/or providers of data (when they are writing the letters) and implicitly devalue African individuals and cultures. This implicit devaluation, which the next section will take up, is a key thematic element of African representation in the language of missionary periodical texts featuring BIPOC creators.

Erasing African People, Agency, and Perspectives

The use of quantifiable conversion data as the primary means of representing African peoples in Protestant missionary periodicals served an institutional purpose that implicitly undervalued individuals and erased any non-Christian agency. Martin Petzke (2018, 204) analyzes the rise of quantification in missionary work through the lens of field theory. He argues:

Quantifications of successful conversions, often to the point of triumphalism, demonstrated the legitimacy of the missionary enterprise, while quantifications of heathens continued to serve as a reminder of the unresolved task. Both approaches were reconciled in numerical calculations considering the possibility of evangelizing the world ‘in this generation,’ validating the feasibility of the missionary endeavor as such.

The rise of quantitative language can be directly tied to the discursive, ideologically-loaded invention of a “‘heathen population’” (Petzke 2018, 185) and a “foreign ‘other’” (Jensz and Acke 2013, 368). The process of quantification of non-Christian populations, as seen in the examples in the prior section, helped to establish a tangible goal for European missions which helped to legitimize their work.

Not only did the use of quantifiable conversion data implicitly erase African perspectives, it also served a deliberate institutional purpose:

In reporting the abhorrent moral conduct of the so-called heathen, missionary periodicals reflected the moral anxieties of the age, and thus reveal how editors wished to shape their reading communities, the support of which in both spiritual as well as material goods was fundamental to the missionary endeavor. (Jensz and Acke 2013, 369)

Language in missionary periodical texts that both quantified and continued to reaffirm the presence of a “heathen population” helped to generate urgency around their missions, an urgency that tied directly back to a European audience whose financial and moral support upon which endeavors relied (Petzke 2018, Wild-Wood 2021).

In addition to quantifiable conversion data, some missionaries wrote in a way that was critical of both unconverted African peoples and their ways of life to contrast with the “morally upright” Christian population. Another segment of Dwane’s letter ([1877] 2022) illustrates this point:

This is the busiest town I have seen yet. I don’t know if you noticed when you were here, how small Kafir huts are; but I know that you saw plenty of them when you went into Kafirland. They are small round little things built in the shape of an ant-hill. The location is so full of people that there are often about twenty men in a hut. But the more enlightened natives, especially Christians, have square houses, two or three rooms each. I am very glad for this, for I do really think that these miserable huts are not only mothers of disease, not only obstacles to civilization, but they are stumbling-blocks to Christianity.

Language – written and spoken – that relegated African peoples to quantifiable data points reinforced the idea of a “heathen population” (Petzke 2018, 185) and served to silence or discredit non-Christian perspectives while ensuring support from the periodicals' readership. This is particularly noteworthy in Dwane’s commentary in the above excerpt. His writing echoes the same strategies employed by white missionaries to further characterize African peoples as heathens (i.e., non-Christian).

This calls into question the bias of the editors themselves, particularly the way language was used within these Protestant missionary periodicals. Indeed, although there exists published evidence of missionaries celebrating the character of African peoples, such instances were often presented as an afterthought or bookended by quantifiable language that deemphasized these anecdotes.

Representational Tensions

There existed a tension in the periodical language of Protestant missionaries between prejudiced representation of African peoples and positive representation that celebrated the Christian potential of those peoples to the European readership. Despite the organizational impulse to establish a “heathen population” (Petzke 2018, 185) and the devaluation of African voices through the use of quantifiable conversion data, many missionaries did represent the African peoples in a positive light. However, an analysis of the language used in missionary periodicals that celebrates African peoples showed a propensity, nonetheless, to qualify any positive representation by underscoring the influence of Christianity. As a result, both the positive and prejudicial representations implied that African peoples required the imposition of a Christian framework.

In an anecdote, John Philip ([John] Philip, Edward Edwards, and Anonymous [1823] 2022) recalls “Africaner,” an African man who was celebrated for his highly Christianized characteristics. In Philip’s account, Africaner was represented as growing from “savage leader of a savage tribe” into a man who “exemplif[ies] in a high degree the graces of the christian parent and master,” who carries himself “with much humility, zeal, diligence, and prayer,” and who is “a man of considerable natural talents, of undissembled piety” – one who “possessed an experimental and an enlarged acquaintance with his Bible” ([John] Philip, Edward Edwards, and Anonymous [1823] 2022). Furthermore, after describing Africaner’s piety and humility in receiving a wagon as a gift from the Colonial Government, Philip writes (with admittedly problematic language) of Africaner and his community as follows:

He was a Hottentot, and I think a sufficient refutation of that old charge, that Hottentots have no minds and are not capable of improvement, and therefore cannot and ought not to be put upon a level with other nations, as it respects intellect. The Hottentot’s powers have been much underrated. ([John] Philip, Edward Edwards, and Anonymous [1823] 2022)

The term ‘Hottentot’ has a complicated history. Early uses of the term appeared in the late seventeenth century and were used to reference the Khoi peoples and other indigenous groups of South Africa in a way that became more and more pejorative (for more, see Maas 2022). However, Philip’s evaluation of Africaner runs counter to public opinion of the time and also stands in contrast to the devaluation of African populations through quantitative conversion data, as discussed above. At the same time, Philip’s reframing of Africaner (and, subsequently, Africaner’s community) is qualified through reference to the influence of Christianity. The way this evaluation is elaborated in the Missionary Chronicle shows how – in Protestant missionary periodicals – the only opportunity for African peoples to overcome westernized standards of value is to comply with Christian-biased characteristics.

In another segment of his letter, Dwane ([1877] 2022), like Philip, qualifies positive evaluation through reference to Christianity. Dwane does this by relating the story of Margaret, a girl who died in his presence. Like Africaner, Margaret is celebrated for her Christian characteristics and her piety in the face of persecution. Dwane represents her as a martyr whose faith in Christianity and involvement in the local school was challenged by her aunt. As Dwane ([1877] 2022) writes, Margaret was persecuted by her aunt “until God interfer[es] and la[ys] her aunt on a bed of sickness.” Dwane ([1877] 2022) goes on to recall Margaret’s baptism before her death which had a profound impact on the community:

I remember a very wicked man, who is known in most of the colonial towns as a notorious sinner, came to me and said, ‘I wish I could die like Margaret;’ and I told him to live like her, if he wants to die like her. Her death was really wonderful, and made a great blessing to the people of this town.

Again, it’s not possible to know how much of this anecdote is biased by Dwane’s position in the mission or the biases of an unnamed editor, but it’s worth recognizing the trend in positive representation of African peoples. Presumably, Margaret and her aunt died of the same illness, but Margaret’s is here represented as an act of divine intervention. In Dwane’s version of the narrative, Margaret becomes a martyr whose death provided clarity and enlightenment, a “success story” for the missionary audience.

Ryan Fong (2020) notices similar trends in his analysis of South African oral storytelling and its representation in Victorian literature. He comments on the presence and influence of “settler-editors” (425) who collected stories from African cultures and produced them within a western context for a western audience. The work of these editors, Fong claims, is influenced by “white supremacist terms of recapitulation theory, which equates African peoples with European children” (425).

Similar to Fong’s commentary on the biased work of European editors who collated these oral stories, missionary periodicals show a trend in the influence of missionary periodical editors. The representation of Africans in missionary periodicals differs from what Fong discusses because of the insistence on Christian mores. The need of missionaries to affirm their place and authority as Christians demanded proof of piety which surely influenced the editorial work and excerpts chosen by missionary periodical editors before final publication (Nickel 2015, 123).

Margaret Beetham (1989, 98) helps clarify the foregoing point by outlining a key approach for contextualizing the periodical as a distinct genre. She borrows two terms from psychoanalytic theory to define cultural forms of meaning-making: “open” and “closed.” Open forms provide numerous avenues to reach a meaning and allow for various meanings to emerge, where closed forms are more assertive in their structure, often allowing a single way of making meaning of a text or artifact. Beetham argues that, despite the strict structure of periodical production and distribution, it can generally be read as an open form.

However, considering the above examples of theologically-biased language and the way positive representation of African peoples was qualified through the addition of Christian characteristics, it is hard to argue against the missionary periodical as a closed form. The above extracts from Dwane and Philip strongly suggest a closed model of representation and character evaluation. Both examples provide a single way of making meaning, a Christian way, and thus a single way of making sense “by analogy, of the world and the self” (Beetham 1989, 98). Missionary periodical editors continuously link positive characteristics to Christian piety, thus relegating any African person who doesn’t fit this description to the quantifiable “heathen population” (Petzke 2018, 185).

Conclusion

Missionary periodicals from the nineteenth century function as unique objects due to their diverse authorial presences. The periodicals provide a literary landscape that purported to represent both European and BIPOC voices within a singular publication. However, as this essay shows, a detailed analysis of the language in select missionary periodical texts suggests that the periodicals, at best, offered biased representations of African peoples, even when the representations appeared to be in the voices of Africans themselves.

Texts that appear to be authored by African contributors themselves are often unrecognizable from those authored by European missionaries, particularly due to the fact that the language used to represent the voice of African peoples echoes a nineteenth-century mindset that undervalues such peoples. Such characteristics suggest the often-silent influence of missionary periodical editors.

While it may not be possible to determine the extent of such editorial work, it is clear that these periodicals prioritized institutional requirements over individual representation by including sections that highlighted quantitative conversion data. Additionally, when the periodicals introduced positive recognition of African peoples, the periodicals used language to characterize the African peoples as influenced by Christianity. These characteristics and others are due to the fact that successful missions were more likely to secure funding and other means of support.

Further scholarly research on the pieces identified and documented by the “BIPOC Voices” project would do well to recognize the implications of language that devalues the BIPOC populations that these periodicals purport to represent. By calling attention to biased representation, scholars who work with missionary periodicals will help to undo the work of silencing African peoples.

Scholarship that aims to represent missionary periodicals as a neutral source threatens to perpetuate into the twenty-first century the same Victorian-era ideologies that allowed for BIPOC peoples to be represented as data points in missionary endeavors instead of as individuals. There is no doubt that missionary periodicals offer unique insight, but in working with the periodicals scholars must intentionally qualify these texts and their problematic contexts.

A long line of scholars working in postcolonial studies, most influentially Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (1985; 1988), have raised the question of whether there is any possibility of returning to anything like an “authentic” BIPOC voice. Reading against the grain of such erasure may indeed be impossible, particularly in the case of published missionary periodical texts (such as those taken up in the present essay) for which the original manuscript documents do not survive.

This point, in terms of the missionary periodicals, applies equally to texts represented as being written by either British or BIPOC contributors due to the impossibility of knowing conclusively (without other evidence) the influence that white British periodical editors had in shaping the texts.

Unpublished archival texts will not necessarily be more “truthful,” but will potentially involve fewer layers of mediation than published texts (see, e.g., Bridges 1987; 1998; Youngs 1994; Wisnicki 2019), especially in those cases where relevant missionary periodical texts survive as written in the hands of BIPOC authors (see Cason 1981; the Church Missionary Society holdings of the University of Birmingham’s Cadbury Research Library may be particularly useful in this regard).

This essay, in turn, doesn’t attempt to make claims about the possibility of recovering BIPOC voices in some unadulterated form. Rather this essay, like others in the “BIPOC Voices” project (e.g., Goh 2022), examines the question of how scholars might better use missionary periodical texts that feature BIPOC creators as evidence for historical or other forms of scholarly analysis (also see the “Project Findings“ of the “BIPOC Voices” project as a whole).

Fundamental to such an endeavor is a solid understanding of how these periodical texts function as discursive objects, particularly in terms of the use of stylized language and strategies of rhetoric and representation. This goal has motivated the present essay. Achieving this goal promises to assist scholars who might be considering engaging with similar types of periodical pieces or other such texts in their own work as part of a larger endeavor in Anglophone and British literary studies to develop a new, multidimensional history of nineteenth-century intercultural encounter.

Citation Practices in this Essay

The project team for “BIPOC Voices” encountered a variety of non-European names in the project's periodical pieces for which it proved difficult to determine what qualified as the forename and surname or if such a distinction was even appropriate for the given cultural context. The project's limited scope prevented full investigation of each case. As a result, the team decided that referencing of the project's primary texts in both in-text citations and “Works Cited” lists would use the full name of each primary text contributor – non-European and European – in the order given in the text.

The result is that all project materials consistently follow two citation practices. For periodical piece contributors, the project materials use full names in the original order for all individuals for citation purposes. For the authors of other primary and secondary texts, the project materials default to using only surnames for in-text citations and to following the convention of "surname, forename" in “Works Cited” lists. (See Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom's lesson plans on “Transimperial Networks and East Asia” for a comparable use case.)

Works Cited

Anonymous, Charles Pamla, and Boyce Mama. (1872) 2022. “South Africa. Graham’s Town District.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Trevor Bleick, Kasey Peters, and Kenneth C. Crowell, translated by James Dwane, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, and Diphukwe. (1878) 2022. “Central South Africa.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Kasey Peters, Trevor Bleick, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Anonymous, [W.J. Davis], and James Lewana. (1872) 2022. “South Africa.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Trevor Bleick, Kasey Peters, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Beetham, Margaret. 1989. “Open and Closed: The Periodical as a Publishing Genre.” Victorian Periodicals Review 22 (3): 96–100.

Bridges, Roy C. 1987. “Nineteenth-Century East African Travel Records with an Appendix on ‘Armchair Geographers’ and Cartography.” Paideuma 33: 179–96.

Bridges, Roy C. 1998. “Explorers’ Texts and the Problem of Reactions by Non-Literate Peoples: Some Nineteenth-Century East African Examples.” Studies in Travel Writing 2 (1): 65–84.

Comaroff, Jean, and John Comaroff. 1991. Of Revelation and Revolution: Christianity, Colonialism, and Consciousness in South Africa. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Comaroff, John L., and Jean Comaroff. 1997. Of Revelation and Revolution: The Dialectics of Modernity on a South African Frontier. Vol. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cason, Maidel. 1981. “A Survey of African Material in the Libraries and Archives of Protestant Missionary Societies in England.” History in Africa 8: 277–307.

Elbourne, Elizabeth. 2002. Blood Ground: Colonialism, Missions, and the Contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799-1852. Montreal; Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Evan Evans. 1822. “Extracts from His Letter, Dated 12th Sept 1821, The Paarl.” Missionary Chronicle 1 (2): 119–20.

Fong, Ryan. 2020. “The Stories Outside the African Farm: Indigeneity, Orality, and Unsettling the Victorian.” Victorian Studies 62 (3): 421–32.

Gates, Henry Louis. 1985. “Editor’s Introduction: Writing ‘Race’ and the Difference It Makes.” Critical Inquiry 12 (1): 1–20.

Goh, Jun Yi. 2022. “Manipulating Indian Voices in Victorian Missionary Periodicals.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, peer reviewed by Sutanuka Ghosh and Adrian S. Wisnicki, solidarity edition.

Jensz, Felicity, and Hanna Acke. 2013. “The Form and Function of Nineteenth-Century Missionary Periodicals: Introduction.” Church History 82 (2): 368–73.

J.M. Dwane. (1877) 2022. “South Africa.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Kasey Peters, Trevor Bleick, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

[John] Philip, Edward Edwards, and Anonymous. (1823) 2022. “Africa. Character of Africaner.” In One More Voice: BIPOC Voices in the Victorian Periodical Press, edited by Trevor Bleick, Kasey Peters, and Kenneth C. Crowell, solidarity edition.

Maas, Tycho. 2022. “Turning the Stereotype Against Itself: A VOC Clerk, ‘Hottentots’, and the Formation of Colonial Discourse.” Critical Arts, June, 1–13.

Nickel, Sandra. 2015. “Intertextuality as a Means of Negotiating Authority, Status, and Place – Forms, Contexts, and Effects of Quotations of Christian Texts in Nineteenth-Century Missionary Correspondence from Yorùbáland.” Journal of Religion in Africa 45 (2): 119–49.

Petzke, Martin. 2018. “The Global ‘Bookkeeping’ of Souls: Quantification and Nineteenth-Century Evangelical Missions.” Social Science History 42 (2): 183–211.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1985. “Can the Subaltern Speak? Speculations on Widow-Sacrifice.” Wedge 7–8 (Winter-Spring): 120–30.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 271–313. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Volz, Stephen. 2020. “‘But I Know You, You Are Not God’: African Responses to European Colonialism in a Missionary Newspaper.” Journal of Southern African Studies 46 (4): 597–613.

Werner, Winter Jade. 2018. “‘Altogether a Different Thing’: The Emerging Social Sciences and the New Universalisms of Religious Belief in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 73 (3): 293–325.

Wisnicki, Adrian S. 2019. Fieldwork of Empire, 1840–1900: Intercultural Dynamics in the Production of British Expeditionary Literature. New York; Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Wild-Wood, Emma. 2021. “The Interpretations, Problems and Possibilities of Missionary Sources in the History of Christianity in Africa.” In World Christianity: Methodological Considerations, edited by Martha Frederiks and Dorottya Nagy, 92–112. Leiden: Brill.

Youngs, Tim. 1994. Travellers in Africa: British Travelogues, 1850-1900. Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press.