Overview

Our project design, which enables much of our work, depends on a few key elements, with the most important being minimal computing, accessibility, and digital recycling. This page provides a short history of One More Voice in order to give some context for the development of our key design elements, then offers a brief summary of our work in relation to each of the elements.

Early Project History (2008-20)

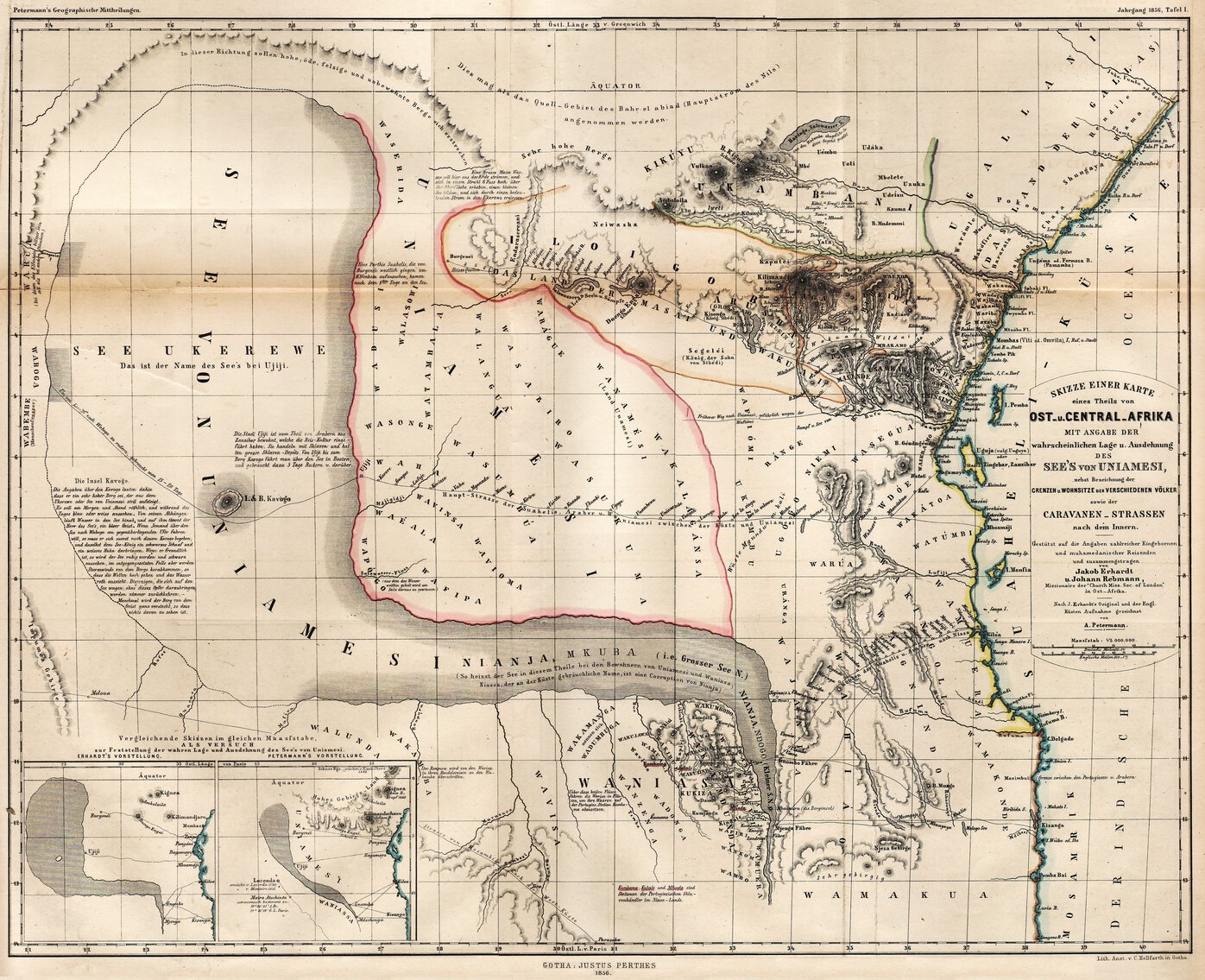

Adrian S. Wisnicki, the lead developer for One More Voice, first conceived of a project along these lines in the late 2000s, while working with the periodical publications of Victorian-era “armchair geographers” like W.D. Cooley and James McQueen for what would become a monograph called Fieldwork of Empire (2019; also see lead image and lead image details for the present page).

In studying these periodical publications, Wisnicki became aware of their multifaceted nature – that these pieces, nominally authored by British individuals, often incorporated considerable data from a variety of African and Arab informants and, in some cases, included the actual narratives of those informants. Nearly a decade of subsequent work for Livingstone Online (2010-18) further complicated the notion of authorship in the context of such imperial and colonial materials, as Wisnicki and his project collaborators repeatedly came across instances of informant data and, in some cases, even writing in other hands in Livingstone’s manuscripts.

Wisnicki’s desire to bring these materials to the notice of other Victorianists, as a way of complicating the critical notion of Victorian-era authorship while diversifying the primary content studied in the field, led to the first steps in designing and implementing the actual One More Voice site. These steps included pre-pandemic presentations on the project at the conferences for the British Association for Victorian Studies (BAVS; 2018), the North American Victorian Studies Association (NAVSA; 2018), and The Northeast Victorian Studies Association (NVSA; 2019).

Wisnicki also secured a small ENHANCE Grant from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (2020) to support the work. He developed this grant specifically as a way of funding a month of sabbatical research (March 2020) at the Special Collections of SOAS Library and the National Library of Scotland. The planned research centered on identifying materials relevant to One More Voice, with the goal of using these materials to launch the website in late 2020.

However, the global arrival of the Coronavirus pandemic in early 2020 changed everything. In Wisnicki's case, it compelled him to cancel his travel plans at the last moment, three days before his scheduled departure date of March 9, 2020. During the subsequent months, Wisnicki and a set of core collaborators from Livingstone Online turned to collaborating synchronously and asynchronously to develop the first version of the One More Voice. This work gave Wisnicki some chance of salvaging his otherwise failed sabbatical plans and offered everyone involved a respite from the continuous inundation of pandemic-related news.

After a few focused months of development, Wisnicki and his team launched the One More Voice website on June 8, 2020, coincidentally just a little over two weeks after the murder of George Floyd and the start of a wide-spread national reckoning on race and global movement in support of Black Lives Matter. Such developments and the 2020 summer events that followed far overshadowed in significance scholarly initiatives like the launch of One More Voice. However, the developments – alongside the publication of the groundbreaking “Undisciplining Victorian Studies” essay on July 10, 2020 by Ronjaunee Chatterjee, Alicia Mireles Christoff, and Amy R. Wong – gave a new meaning, context, and impetus to the One More Voice project and have continued to inform each of the site's three development phases to date.

Site Development Phases (2020-22)

As noted, One More Voice has passed through three development phases since 2020, each centered on the publication of a new edition of the site. The first phase resulted in the “Site Launch Edition” (2020-21) and focused on establishing a proof-of-concept version of the site. This version:

- Identified and published a selection of representative archival texts (manuscripts and periodicals articles) in critically-encoded editions;

- Documented and, in some cases, published other relevant materials (visual materials, book-length works, motion pictures);

- Leveraged a variety of minimal computing strategies to make the site accessible to diverse audiences;

- Defined key site practices, including the use of digital recycling and open peer review (PDF); and

- Brought together a network of contributors to support content development.

The first phase also set the stage for the second phase, which launched in late 2021 with the publication of the “New Dawn Edition” (2021-22). This phase focused on widening the scope of One More Voice, both in terms of materials published and partnerships established. The phase increased the number of primary materials published on the site to over eighty items, incorporated numerous new creator images, and added a series of peer-reviewed critical essays. The phase also witnessed the launch of a series of collaborative ventures centered on developing larger-scale thematic initiatives.

Finally, the third phase – currently underway – has resulted in the “Solidarity Edition” (2022-present) of the site, published in late July 2022. This edition represents a significant departure from prior editions. We have completely redesigned the front end of One More Voice so that the site is now much more vibrant in its “look and feel.” We have sought to streamline site navigation in order to make users better aware of the extensive materials published by the site. We have invested considerable effort in further enhancing the site's accessibility features in order to make the site available to an even wider audience. We have also revised and updated our “Mission Statement” so that it accurately reflects the evolving nature and scope of the project.

Additionally, in keeping with the solidarity theme – i.e., the fact that the work of One More Voice is fundamentally relational and that the project's main efforts center on collaboration with individuals and other projects – we have also sought to foreground the various thematic initiatives in which One More Voice is currently involved. These include efforts with COVE, SOAS Special Collections, and Adam Matthew Digital to recover and examine representations of racialized voices in missionary periodicals, and a new partnership with the Ardhi Initiative and archives in Kenya and Britain that will focus on studying land treaties. Notably, grants from the Research Society for Victorian Periodicals (RSVP), the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS), and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) have enabled much of this new collaborative work.

Minimal Computing

Through each of the One More Voice development phases, we have anchored our work on the use of minimal computing. Minimal computing is a low-tech digital humanities methodology that has gained considerable traction among practitioners in recent years. A fundamental element of the methodology lies in its emphasis on creating digital projects that rely on reduced resource use, as in the early case of the Periodical Poetry Index (2010-present) and as later elaborated in work by Alex Gil, Jentry Sayers, Roopika Risam and Susan Edwards (PDF), and others. By building on such scholarship, we have engineered a site development method that is self-empowering and that allows for collaboration with scholars with a range of technical competencies.

Minimal computing has also enabled us to develop the One More Voice website in a way that is easy to maintain, has the potential for long-term survival by relying on standard flat file formats, and can be hosted online on various free platforms. The site consists mainly of 1) HTML and CSS files, 2) a few Javascript files, 3) compressed JPEG images scaled to responsive sizes (mobile, iPad, laptop, desktop, etc.), 4) XML and TXT files for primary content, and 5) supporting Word and PDF files. Due to these formats and the overall site design, users and developers can easily access site content separate from the site itself, thereby allowing for wider reuse and dissemination of all site materials.

Other elements support these core practices; some center on reducing resource needs; others allow us to sidestep what might otherwise be necessary expenditures. The emphasis on a small digital footprint (225 MB as of July 2022; this includes a TXT file-based corpus of 6.5 million words), for example, means that One More Voice remains portable and does not have complex publishing platform requirements. A dedicated Zotero library serves as both a metadata repository and a way to organize, export, and share all bibliographic records. We also document all metadata for primary materials in a standalone Excel spreadsheet (XLSX). Together, the Zotero library and Excel spreadsheet have, so far, enabled us to forego the costs associated with building a full-scale database. Finally, GitHub provides both free code versioning and site hosting, while Cloudflare serves as a free content delivery network (CDN). Use of these two resources means that we can keep our site stable and fast, but also that the only recurrent site cost is $20/year for the domain name.

Accessibility

Recourse to minimal computing has freed up considerable time and resources for other activities, thereby allowing us to prioritize accessibility as a foundational component of site design. Our site incorporates numerous features to support accessibility. For example, we consistently use semantic HTML headings and landmarks, ARIA attributes, and descriptive ALT text for images to enable access by visually impaired users and those who rely on assistive devices. We provide clear and consistent navigation, while employing a simple but elegant aesthetic framework that cuts down on visual noise and clutter. We incorporate a color blind-safe color scheme for all the site pages. Key features of our recovered texts (such as color, justification, and rotation) can be toggled on and off as needed, while short object descriptions convey verbally the manuscript material characteristics documented visually by our digital facsimiles. We also provide descriptive and accessible tooltips for all Font Awesome icons.

Beyond such prominent elements, we include a number of features that support keyboard accessibility, such as fully-operational tab navigation and options to skip repetitive content like menus (all pages) and YouTube video controls (Motion Pictures page). The addition of the Google Translate widget has made it possible for visitors to generate rough translations of each of our site pages into over 100 languages. Finally, we inform all our efforts to promote accessibility by reference to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) and WAI-ARIA Authoring Practices, and we consistently check our work against WebAIM’s Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool (WAVE) and Google’s Lighthouse. Collectively, these many practices open our site to users with disabilities and ensure that we can deliver content around the world, to multiple kinds of devices, at a low cost, and in environments of varying bandwidths.

Digital Recycling

Our use of digital recycling, the last of our key site design elements, also grows out of our application of minimal computing and supports our efforts to prioritize accessibility. Digital recycling involves the strategic reuse of existing digital materials and tools. In our project's startup phase (see above), recourse to digital recycling enabled us to avoid many of the challenges involved in new site development because we could draw key components from elsewhere and did not need to create them from scratch. For example:

- We appropriated the foundational HTML and CSS code for our site from the Fieldwork of Empire minimal computing website (2019), a site expressly built to serve as a prototype for the present site;

- We made it possible to draw on Livingstone Online primary materials, publication strategies, and workflows as needed by positioning One More Voice as a descendant or “imprint” site of the former;

- We streamlined the existing Livingstone Online coding guidelines to create the coding guidelines (PDF) for the One More Voice site; and

- We used open-access online repositories like the HaithiTrust and Internet Archive to supplement the materials available from Livingstone Online plus leveraged existing collaborations with the Special Collections of SOAS Library, the National Library of Scotland, and the Bodleian Libraries to gain access to other relevant historical materials.

An overall digital recycling ethos also continues to keep our site’s digital footprint small by encouraging us to link to many online items (e.g., videos, book-length works, and high-resolution images) rather than hosting them ourselves.

Ultimately, by practicing digital recycling, we have been able to create a multifaceted, open access resource – the One More Voice site – that might itself now be recycled in other contexts. In fact, Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, an independent but affiliated project, started up as quickly as it did (2020-21) in part because it developed its own site code by drawing on and enhancing the existing site code for One More Voice.

Conclusion

Although One More Voice relies on a relatively uncomplicated technological infrastructure, the site’s overall development ethos reflects a long history of preparation and embodies the result of highly intentional design choices. These include the decision to apply minimal computing as a way of reducing resource needs, prioritizing accessibility as a way of bringing the project to a wide audience, and using digital recycling as a strategy for streamlining site development. Together, these elements have made it possible for the project team to work at a manageable scale, produce high-quality scholarship, and realize at the technical level the same kind of human-centered, scholar-led ideals that animate the conceptual and public-facing dimensions of the project.